Endoscopy: Bronchoscopy and Esophagoscopy

Abbas E. Abbas

INTRODUCTION

Traditional endoscopy allows the evaluation of the endoluminal aspect of the tracheobronchial tree and the foregut. Newer advances such as endosonography and electromagnetic navigation have broadened the scope to include information outside the immediate lumen. The indications have evolved from a simple diagnostic procedure to one that may also be therapeutic or for staging of thoracic malignancies. The impressive technological advances in the field of fiberoptic endoscopy over the last decade now allow us to have access to areas previously considered “blind” by traditional endoscopy. For example, electromagnetic navigation can help to accurately navigate the bronchoscope to a peripheral lung nodule. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) allows us to visually assess a mediastinal lymph node in real time while simultaneously performing a transbronchial fine needle aspiration. Rigid endoscopy, whether esophageal or bronchial, remains as important for the thoracic surgeon to master today as it always has been. Although flexible endoscopy has taken away some of the indications for the rigid procedures, such as dilation and stenting, rigid endoscopy still plays a vital role for the thoracic surgeon and at times may be life-saving. The main advantage of rigid endoscopy is the ability to use larger instruments. This allows better biopsy specimens, debridement of tissues, and suctioning of fluids and debris. Rigid endoscopy is also necessary for certain stent placements in the airway. Although it is possible to perform all endoscopic procedures, including even rigid endoscopy, under local anesthesia or with simple sedation, advanced endoscopies are sometimes quite lengthy and safer to perform under general anesthesia. The choice of analgesia and anesthesia should be determined on an individual basis and according to pathology or operator preference.

ANATOMY

ANATOMYIt is important for the endoscopist to have a clear understanding of both the endoluminal and the external relationship to overlying mediastinal structures. This is especially important for EUS and this is also where surgeons have a distinct advantage.

Pharynx and Larynx

Aerodigestive anatomy begins with the entry of air into the body via the nasopharynx and the oropharynx. Entry may be gained to the upper aerodigestive system through either the nose or the mouth. At the nares, there is a 3- to 4-mm opening below the lower turbinates, with direct access to the posterior pharynx. This entry is just medial to the pharyngeal tonsil and passes posterior to the soft palate. Entry through the mouth reaches the posterior pharynx beyond the soft palate. As the posterior portion of the tongue is passed, one reaches the vallecula. At this level, the epiglottis can be seen anterior to the aerodigestive tract. Immediately posterior to this structure, the vocal cords can be seen easily. They are attached anteriorly and move apart posteriorly. The vocal cords are bounded by the aryepiglottic fold and posteriorly by the corniculate tubercles. Just posterior to the tubercles is the entrance to the esophagus. Laterally, on both sides of the esophagus, are the pyriform recesses, which are often mistaken for the true esophagus but are false passages with a depth of 2 to 3 cm.

Bronchoscopic Anatomy

A complete bronchoscopic examination will inspect the divisions of the tracheobronchial tree to the level of the segmental and subsegmental orifices.

Trachea

The trachea begins inferior to the glottis, at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra. Distally, it divides into the left and right mainstem bronchi at the carina. The location of the carina is usually at the level of the fifth thoracic vertebra, which is in line with the angle of Louis. This may ascend or descend up to two vertebrae with breathing. The internal diameter is about 16 mm while the length of the trachea varies according to the height of the individual and is about 12 cm. Surgically, the trachea is divided into two parts; the cervical trachea from the glottis to the manubrium and the thoracic trachea from the manubrium to the carina (Fig. 1.1).

The wall of the trachea is formed of fibromuscular tissue which is reinforced anteriorly by 16 to 20 incomplete cartilaginous rings. These rings form the anterior two-thirds of the tracheal circumference. The posterior wall is a flat fibromuscular membrane, which is immediately anterior to the esophagus.

The thoracic trachea is crossed anteriorly by the left innominate vein. Immediately inferior to the vein, it lies behind and to the right of the arch of the aorta and is straddled by the innominate artery on the right and the left common carotid artery on the left. Laterally on the right, the superior vena cava runs longitudinally adjacent to the trachea. Paratracheal and subcarinal lymph nodes lie in direct relationship to the trachea.

Mainstem Bronchi

The right mainstem bronchus (RMSB) arises from the carina at an angle of 30 degrees while the left mainstem bronchus (LMSB) has a sharper turn closer to 45 degrees. The diameter of the RMSB is also larger than the LMSB (16 vs. 13 mm). These are the reasons for the difficulty in intubating the left bronchus compared with the right, and for why inhaled foreign bodies are found more often on the right side.

The RMSB is usually about 1- to 2.5-cm long and ends after giving off the right upper lobe (RUL) branch. Its continuation then becomes the bronchus intermedius

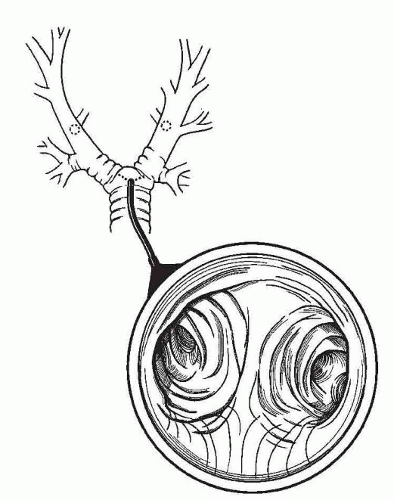

(BI), which is also about 2-cm long. The RUL bronchus (Fig. 1.2) comes off perpendicularly to the RMSB and gives off three segmental branches. Its location can vary in different individuals and may even arise as a direct branch of the trachea. It is saddled by the azygos vein laterally and lies superior then posterior to the right pulmonary artery. The BI then terminates as a bifurcation to the middle and lower lobe bronchi (Fig. 1.3). The right middle lobe (RML) bronchus usually arises directly opposite to the superior segmental branch of the right lower lobe (RLL), but may be just higher or lower, a relationship that is important to determine when performing lobectomy.

(BI), which is also about 2-cm long. The RUL bronchus (Fig. 1.2) comes off perpendicularly to the RMSB and gives off three segmental branches. Its location can vary in different individuals and may even arise as a direct branch of the trachea. It is saddled by the azygos vein laterally and lies superior then posterior to the right pulmonary artery. The BI then terminates as a bifurcation to the middle and lower lobe bronchi (Fig. 1.3). The right middle lobe (RML) bronchus usually arises directly opposite to the superior segmental branch of the right lower lobe (RLL), but may be just higher or lower, a relationship that is important to determine when performing lobectomy.

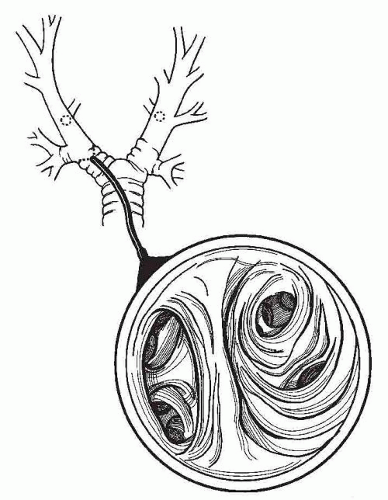

The LMSB (Fig. 1.4) is longer than the right and averages 5 cm. It passes underneath the aortic arch and crosses anterior to the esophagus, the thoracic duct, and the descending aorta. It lies posterior and then inferior to the left pulmonary artery. The bifurcation of the LMSB into the left upper lobe and the left lower lobe bronchi is often called the secondary carina.

Bronchopulmonary Segmentation

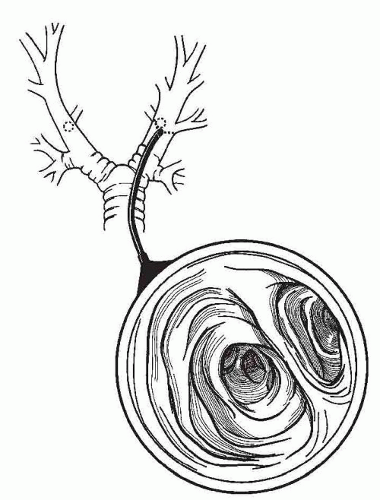

Primary branches of the lobar bronchi are called segmental bronchi and each leads to a structurally separate unit called the bronchopulmonary segment (Table 1.1 and Fig. 1.5). These number 10 in the right lung and 8 in the left. The RUL bronchus divides into three segmental bronchi, namely, the apical, posterior, and anterior segments. The RML bronchus divides into the medial and lateral segments. The RLL bronchus divides into the superior segment and four basal segments, including the anterior, medial, lateral, and posterior basal segments. The left upper lobe bronchus divides into an upper division and a lower division. The upper division, or upper lobe proper, gives rise to the apicoposterior and anterior segments. The lower division, or lingual, gives rise to the superior and inferior segmental bronchi. As on the right side, the first segmental branch of the LLL bronchus is a large superior segmental bronchus. This is followed by the basal segments, which number only 3 on the left side; anterior basal segment, the lateral basal segment, and the posterior basal segment.

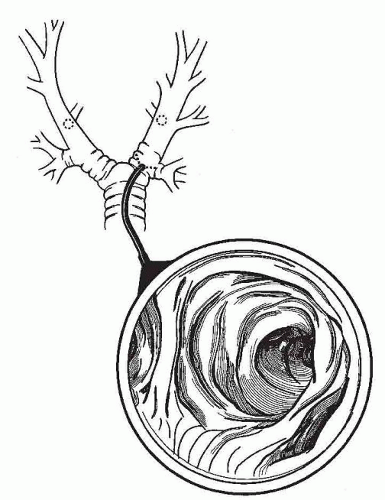

Fig. 1.3. The view down the bronchus intermedius showing the middle lobe and the lower lobe orifice. |

The Esophagus

The esophagus, or gullet, is a long muscular tube that connects the pharynx to the stomach. The length of the esophagus in adults is about 25 cm and, like the trachea varies with the length of the individual. It extends from the cricopharyngeus muscle at the level of the cricoid cartilage and the sixth cervical vertebra to the cardiac orifice of the stomach at the level of the 11th thoracic vertebra.

Along its course, the esophagus is in the midline, anterior to the spine except for two leftward curves. At its origin, the esophagus curves gently to the left down to the level of fifth thoracic vertebra where it returns to the midline. The second is a sharper curve to the left and is formed as the esophagus traverses the diaphragm at the hiatus where it turns to cross the descending thoracic aorta and enter into the stomach.

The esophagus also follows the convex and then concave curvatures of the cervical and thoracic spine.

The esophagus also follows the convex and then concave curvatures of the cervical and thoracic spine.

Table 1.1 Segmental Airway Anatomy | ||

|---|---|---|

|

In endoscopy, the parts of the esophagus are described according to the distance from the upper incisor teeth. The upper esophageal sphincter (UES), or cricopharyngeus, is at 15 cm whereas the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) is at 40 cm. It is important to remember that these levels can vary depending on the height of the patient and also on the timing when measurements were taken. Measurements made while advancing the endoscope tend to be longer than those made during retraction, a phenomenon commonly seen with a sliding hiatal hernia.

Fig. 1.5. Segmental anatomy of the tracheobronchial tree in an orientation akin to that observed when performing bronchoscopy. |

It is also usually divided into cervical, thoracic, and abdominal portions. The cervical portion extends from the cricopharyngeus to the suprasternal notch. The thoracic portion extends from the suprasternal notch to the diaphragm. The abdominal portion extends from the diaphragm to the cardiac portion of the stomach.

The esophagus has three natural constrictions along its course. It is important for the endoscopist to be aware of these locations, especially when searching for impacted foreign bodies or when deciding on the amount of safe dilation for pathologic strictures at those sites. The first constriction is at 15 cm from the incisors, right at the UES and is the narrowest portion of the esophagus. The second is at 23 cm, where the esophagus lies behind the aortic arch and LMSB. The third constriction is at 40 cm, where it traverses the diaphragm at the LES.

Endoscopic Relationships of the Esophagus

It is important to understand the relationships of the esophagus especially when performing EUS or before contemplating certain maneuvers such as dilation and stenting. The cervical esophagus lies posterior to the membranous trachea. It overlies the bodies of sixth, seventh, and eighth cervical vertebra. The bilateral carotid sheath and lateral lobes of thyroid gland are immediately lateral to the cervical esophagus.

The thoracic esophagus lies in the superior mediastinum between the trachea and vertebral column. It then enters the posterior mediastinum by passing behind the aortic arch. Laterally, it is related to the aorta and left subclavian artery on the left while on the right side, it is related to the azygos vein. Anteriorly, the esophagus is related to the trachea, right pulmonary artery, left bronchus, pericardium with left atrium, and diaphragm. Posteriorly, the esophagus is related to the vertebral column, descending aorta, and diaphragm.

The abdominal esophagus passes through the right crus of the diaphragm to lie posterior to the left lobe of the liver.

EQUIPMENT

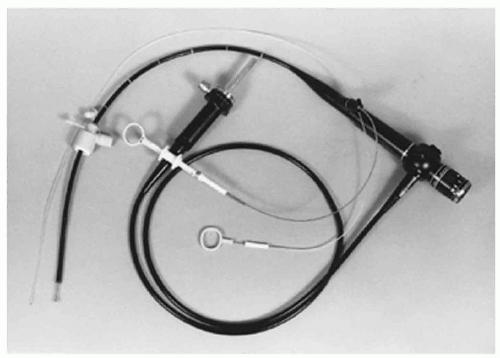

A modern fiberoptic endoscope (Fig. 1.6) basically consists of a handle and a fiberoptic bundle that connects to a light source. There are also one or more working channels for suctioning and for the passage of instruments or injection of liquids. The handle contains one or more knobs to control the position of the tip of the endoscope. Most current bronchoscopes also have a camera adaptor allowing connection to a high-definition monitor (Fig. 1.7).

Bronchoscopy

In addition to performing the visual inspection, there are various options for obtaining material from a bronchoscopy. Brushes can be used to obtain cytology material. The brush is retracted into a sheath after

brushing to protect the specimen. A biopsy forceps is used to obtain material either under direct visualization from the proximal airway or from the peripheral lung parenchyma under fluoroscopic guidance. A transbronchial needle may be used to obtain extrabronchial samples with or without ultrasound guidance. A triple lumen catheter with a double-sheathed telescoping brush enables sampling of lower respiratory tract secretions for microbiologic examination without contamination from the inner channel of the bronchoscope. This is especially useful in the setting of the possibility of lobar pneumonia. When performing lavage for either cytology or microbiology, irrigation is administered through the working channel and a trap is connected to the suction port.

brushing to protect the specimen. A biopsy forceps is used to obtain material either under direct visualization from the proximal airway or from the peripheral lung parenchyma under fluoroscopic guidance. A transbronchial needle may be used to obtain extrabronchial samples with or without ultrasound guidance. A triple lumen catheter with a double-sheathed telescoping brush enables sampling of lower respiratory tract secretions for microbiologic examination without contamination from the inner channel of the bronchoscope. This is especially useful in the setting of the possibility of lobar pneumonia. When performing lavage for either cytology or microbiology, irrigation is administered through the working channel and a trap is connected to the suction port.

Fig. 1.6. Flexible bronchoscope with standard accessories. The endotracheal tube ventilating adaptor, the biopsy forceps, and a disposable brush are shown. |

Fig. 1.7. Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope showing camera adapter, suction port, and biopsy or irrigation port. |

The endoscope diameter ranges from 3 to 6 mm, with a working channel ranging from 1.2 to 3 mm. For routine diagnostic purposes, a standard 3.5-mm endoscope is usually sufficient. If one plans more extensive procedures, a larger endoscope may be necessary. It is advisable to have available a range of sizes to accommodate, the planned procedure. Most bronchoscopic procedures require an endotracheal tube of at least 8 mm. A bronchoscopy adapter for the endotracheal tube allows simultaneous ventilation during the procedure.