In this retrospective cohort observational study, we investigated mortality, ischemic, and hemorrhagic events in patients ≥65 years with atrial fibrillation consecutively discharged from an Acute Geriatric Ward in the period 2010 to 2013. Stroke and bleeding risk were evaluated using CHA2DS2-VASC (congestive heart failure/left ventricular dysfunction, hypertension, aged ≥75 years, diabetes mellitus, stroke/transient ischemic attack/systemic embolism, vascular disease, aged 65 to 74 years, gender category) and HAS-BLED (hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, labile international normalized ratio, elderly, drugs/alcohol concomitantly) scores. Co-morbidity, cognitive status, and functional autonomy were evaluated using standardized scales. Independent associations among clinical variables, including use of vitamin K antagonist–based oral anticoagulant therapy (OAT), all-cause mortality, and fatal and nonfatal ischemic and hemorrhagic events, were evaluated. Further clinical outcomes comparison between patients treated with OAT and those untreated was performed after adjustment for significant differences in patient baseline characteristics with propensity score matching. Of 980 patients discharged (mean age 83 years, 60% women, roughly 30% cognitively impaired or functionally dependent, mean CHA2DS2-VASC and HAS-BLED scores 4.8 and 2.1, respectively), 505 (51.5%) died during a mean follow-up period of 571 days; ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke occurred in 82 (12.3%) and 13 patients (1.3%), respectively, and major bleedings in 43 patients (4.4%). Vitamin K antagonists’ use was independently associated with reduced mortality (odds ratio 0.524) and with a nonsignificant reduction in incidence of ischemic stroke, without excess in bleeding risk. Similar findings were observed in the 2 propensity score–matched cohorts of patients. In conclusion, among vulnerable patients with atrial fibrillation ≥65 years with high post-discharge death rate, OAT was associated, among other multiple factors, with reduced mortality.

Incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AF) increase with advancing age. Although oral anticoagulant therapy (OAT) has been showed to be effective for prevention of cardioembolic stroke in older patients with AF, this therapy is widely underused particularly in the oldest old, who should derive the greatest benefit from anticoagulant therapy. AF in patients aged ≥65 years is frequently diagnosed during hospital stay, and it has been demonstrated that many of these hospitalized patients might not be optimal candidates for anticoagulant therapy, in reason of older age, poorer health conditions, greater number of co-morbidities, worse functional autonomy, and reduced life expectancy than those enrolled in randomized clinical trials with anticoagulants. Moreover, there is scant evidence of efficacy and safety of OAT in real-world medical in patients aged ≥65 years with AF. In this retrospective cohort study, we aimed to assess overall mortality and fatal and nonfatal ischemic and hemorrhagic events and their associations with clinical variables, including OAT, in inpatients with AF aged ≥65 years.

Methods

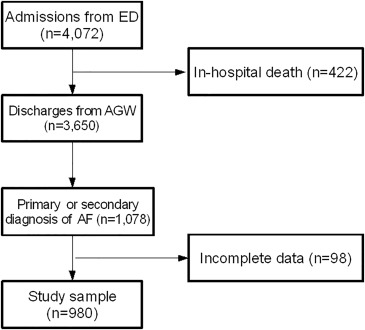

Patients ≥65 years discharged in the period 2010 to 2013 from the Acute Geriatric Ward (AGW) at the Città della Salute e della Scienza-Molinette (a university teaching hospital in Turin, Northern Italy) with a primary or secondary diagnosis of AF (code 427.31 of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9]) were identified from the electronic discharge database. Data were collected by 4 geriatric postgraduate students who reviewed the electronic discharge charts under the supervision of 2 senior geriatricians.

AF was defined paroxysmal, persistent or permanent, according to current international recommendations. Individual stroke and bleeding risk were evaluated according to the CHA2DS2-VASC (congestive heart failure/left ventricular dysfunction, hypertension, aged ≥75 years, diabetes mellitus, stroke/transient ischemic attack/systemic embolism, vascular disease, aged 65 to 74 years, gender category) and HAS-BLED (hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, labile international normalized ratio, elderly, drugs/alcohol concomitantly) scores.

Antithrombotic therapy at discharge was recorded according to the following classes: OAT only, single-antiplatelet therapy, double-antiplatelet therapy, combined double or triple anticoagulant-antiplatelet therapy, and “other,” mainly represented by low–molecular weight heparin. Since in most of the study period in our country, new direct oral anticoagulants were yet not available through the National Health Service, and in this study, OAT included only vitamin K antagonists (VKAs).

In our AGW, all discharge electronic records include several standardized scales that are part of the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. Therefore, indexes of co-morbidity and global physical health (Charlson co-morbidity index), cognitive status (Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire [SPMSQ]), and functional autonomy (Activities of Daily Living [ADL]; Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale) at discharge were also included for analysis. Patients were defined not to have cognitive impairment with SPMSQ scores 0 to 2 and of 3 to 4, 5 to 7, and ≥8, identified mild, moderate, and severe cognitive impairment, respectively. Patients were defined partially or totally dependent in basic daily activities with ADL score of 1 to 2 and ≥3, respectively. Patients were defined dependent in instrumental daily activities with an Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale score of ≤9 of 14. For each patient, creatinine and hemoglobin value at discharge were also recorded.

Follow-up was conducted in the period September to October 2014 by the same 4 geriatric postgraduate students under the supervision of a senior geriatrician through telephone interview with patients or usual caregivers in patients living at home and through review of medical charts in patients resident in long-term facilities. Death, ischemic and hemorrhagic events, and switch of antithrombotic treatment were investigated. Among patients reporting any hospitalization or suspected clinical event of interest, a thorough review of clinical documentation, medical charts, inpatient hospital discharges, and death certificate was performed by a senior geriatrician. Death and its causes were assessed from death certificates, patients’ hospital records, and information from general practitioners or family physicians.

Ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes according to American Heart Association/American Stroke Association definition were recorded. We categorized bleeding events as major and minor events. Major bleeding was defined as fatal bleeding, symptomatic bleeding in a critical area or organ, bleeding causing a decrease in hemoglobin level of ≥20 g/L or leading to transfusion of ≥2 units of whole-blood or red cells, and/or bleeding causing patient’s hospitalization according to current international recommendations.

The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki Title 45, US Code of Federal Regulations, Part 46, Protection of Human Subjects, Revised November 13, 2001, effective December 13, 2001, and according to the Recommendations Guiding Physicians in Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects.

Absolute and relative frequencies of dichotomous and categorical variables and mean and relative distribution of continuous variables were calculated. Associations between variables and fatal and nonfatal clinical end points (death, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, and major extracranial bleedings) were evaluated using ANOVA, chi-square test, and Mann-Whitney test and then using a logistic regression model (forward stepwise method) to evaluate significant independent associations. In addition, a propensity score matching using a 1:1 nearest neighbor–matching algorithm with a ±0.01 caliper and no replacement (yielding 201 propensity score–matched observations) was used to evaluate clinical outcomes after adjustment for significant differences in patient baseline characteristics. Matched sample comparisons were performed with McNemar test, paired t test, and Wilcoxon test.

Results

Of the 4,072 admissions from the emergency department, 422 patients (10.4%) died in hospital, yielding a sample of 3,650 patients discharged from AGW. AF was present in 1,078 (29.5%) of these patients, and 98 had incomplete data and were excluded, leaving a sample of 980 patients eligible for analysis ( Figure 1 ).

Table 1 reports main clinical characteristics of patients studied. Mean age was 83 years and 60% were women, most of the patients had known and permanent AF, with mean CHA2DS2-VASC and HAS-BLED scores of 4.8 and 2.1, respectively. Roughly 1/3 of patients had moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment or were functionally dependent in daily activities. Mean Charlson co-morbidity index and daily number of drugs assumed were 7.4 and 8, respectively. OAT at discharge was prescribed in 384 patients (39.1%), whereas 40.3% were discharged with antiplatelet drugs only, and 10% of subjects did not receive any antithrombotic therapy. Prescription of VKAs at discharge was independently associated with younger age, permanent/persistent AF, home versus long-term facility discharge, higher hemoglobin levels and CHA2DS2-VASC score, lower ADL score (better functional autonomy), and greater number of drugs at discharge.

| Age (years, m±sd) | 83.4±6.7 |

| Female gender | 593 (60.5%) |

| Length of stay (median days [25°-75°]) | 8 (5-12) |

| CHA 2 DS 2 -VASc (m±sd) | 4.8±1.4 |

| HAS-BLED (m±sd) | 2.1±0.9 |

| Atrial fibrillation known before admission | 810 (82.7%) |

| Permanent atrial fibrillation | 720 (73.5%) |

| Charlson comorbidity index (m±sd) | 7.4±2.1 |

| ADL dependent | 263 (26.8%) |

| IADL dependent | 366 (37.3%) |

| Moderate-severe cognitive impairment | 303 (31.0%) |

| Home-discharge | 792 (81.8%) |

| Intermediate or long-term care discharge | 188 (18.2%) |

| Number of therapeutic drugs at discharge (m±sd) | 8.0±2.8 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl, m±sd) | 11.9±2.0 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl, median [25°-75°]) | 1.06 (0.9-1.4) |

| Antithrombotic therapy at discharge: | |

| Oral anticoagulant only | 346 (35.3%) |

| Oral antiplatelet | 369 (37.7%) |

| Double antiplatelet | 25 (2.6%) |

| Low Molecular Weight Heparin | 88 (9.0%) |

| Oral anticoagulant + antiplatelet | 38 (3.8%) |

| None | 114 (11.6%) |

| Antithrombotic therapy at follow-up: | |

| Oral anticoagulant only | 347 (35.4%) |

| Oral antiplatelet | 378 (38.6%) |

| Double antiplatelet | 17 (1.7%) |

| Low Molecular Weight Heparin | 93 (9.5%) |

| Oral anticoagulant + antiplatelet | 31(3.2%) |

| None | 114 (11.6%) |

Outcome clinical events during the period of observation are reported in Table 2 . During a mean follow-up period of 571 days, more than half of patients died; main causes of death included pneumonia, sepsis and infections, myocardial infarction, neoplasms, heart failure, respiratory diseases, falls and trauma, dementia, cachexia, and renal failure. Ischemic stroke occurred in 82 patients (12.3%), and it was fatal in 40 of them. Hemorrhagic stroke occurred in 13 patients, and it was fatal in 11 of them. Major extracranial bleedings occurred in 43 patients, and 2 of them were fatal; minor extracranial bleeding events occurred in 44 patients. All-cause and ischemic stroke–related deaths occurred in 36.5% and 2.9% of patients treated with VKAs and in 61.2% and 4.9% of patients not receiving OAT. At the time of follow-up interview or of clinical events, 378 of 384 patients were still following the anticoagulant therapy prescribed at discharge.

| Clinical events | Overall sample | Oral anticoagulants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| YES | NO | ||

| Follow-up (days, m±sd) | 571±446.3 | ||

| All-cause hospitalization, median (25°-75°) | 1 (0.0-2.0) | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-1) |

| Ischemic stroke | 82 (8.4%) | 22 (6.8%) | 60 (10.1%) |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 13 (1.3%) | 6 (1.6%) | 7 (1.3%) |

| Ischemic events, other sites | 43 (4.4%) | 15 (3.9%) | 28 (4.7%) |

| Major extracranial hemorrhagic events | 43 (4.4%) | 18 (4.7%) | 25 (4.2%) |

| Minor extracranial hemorrhagic events | 44 (4.5%) | 18 (4.7%) | 26 (4.4%) |

| Overall ischemic events | 125 (12.8%) | 41 (8.4%) | 88 (14.8%) |

| Overall hemorrhagic events | 100 (10.2%) | 41 (10.7%) | 59 (9.9%) |

| Fatal clinical events | |||

| Fatal ischemic stroke | 40 (4.1%) | 11 (2.9%) | 29 (4.9%) |

| Fatal hemorrhagic stroke | 11 (1.1%) | 4 (1.0%) | 7 (1.2%) |

| Fatal ischemic events, other sites | 15 (1.5%) | 5 (1.3%) | 10 (1.8%) |

| Fatal extracranial hemorrhagic events | 2 (0.2%) | 0 | 2 (0.3%) |

| Overall mortality | 505 (51.5%) | 140 (36.5%) | 365 (61.2%) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree