Drainage and Debridement of Foot Infections

Neal R. Barshes

Introduction

Healing of diabetic foot ulcers without infection is slow and often incomplete. Following operations done to control foot infection, wound healing is at an even further disadvantage. Failure of wound healing and subsequent progression to major (above-ankle) amputation is common. Despite the fact that operative drainage of foot infections is a procedure very frequently performed by general surgeons, vascular surgeons, and orthopedic surgeons, little literature exists to describe the strategy and techniques. Some discussion of the surgeon’s role in the diagnosis and management of foot is important; however, as delays in diagnosis, ineffective surgical management, and overaggressive resection of soft tissue may negatively prejudice the eventual fate and function of the affected limb.

Behavior of Soft Tissue Foot Infections and Relevant Anatomy

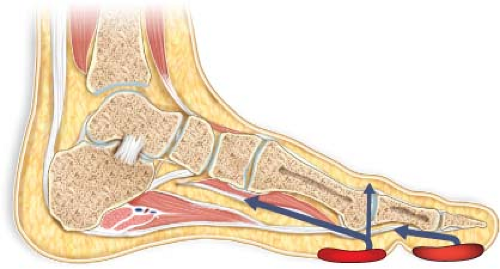

Virtually all foot infections occur because a compromised epithelial barrier (i.e., a wound) allows for the direct inoculation of bacteria into the soft tissue and/or bony structures of the foot. Various forms of wounds serve as these portals of entry for foot infections (Fig. 23.1). Among the more common are ulcers: Epithelial defects of varying depths, with or without overlying eschar or other acellular material. These ulcers typically result from repetitive trauma of walking on a structurally abnormal foot with or without sensory neuropathy. Necrotic toes—which may have resulted from local trauma or inflammation—also represent a wound. Indeed, a necrotic toe is, strictly speaking, an ulcer with a larger amount of overlying necrotic tissue. Lacerations and puncture wounds are less common but may also provide the defect necessary for bacterial inoculation of deeper structures.

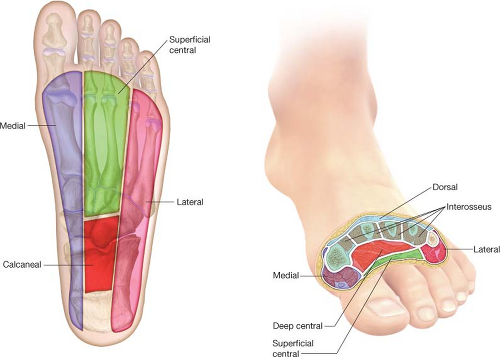

Infections of the foot may affect any of its structures. The range of problems that may occur therefore includes cellulitis, abscesses, fasciitis, tenosynovitis, septic arthritis, myositis, and osteomyelitis. Of these, cellulitis and abscesses are particularly common. The fact that infections of the foot often track along within the fascial planes that define foot compartments, tendons, or other structures has been recognized by surgeons since at least the late 1920s. As such, at least some rudimentary understanding of the

soft tissue anatomy of the foot—especially the compartmental anatomy (Table 23.1 and Fig. 23.2)—is fundamental for all surgeons who are involved in the operative management of foot infections and limb preservation efforts.

soft tissue anatomy of the foot—especially the compartmental anatomy (Table 23.1 and Fig. 23.2)—is fundamental for all surgeons who are involved in the operative management of foot infections and limb preservation efforts.

Identifying a Foot Infection

Foot infections have clear negative impact on the prognosis of a limb, so early identification of infection should be of obvious importance. Although the signs and symptoms are often obvious, the presentation of some infections can be subtle. Thus, the most important strategy for reliably identifying foot infections is to have a high index of suspicion. If signs or symptoms are present, it is generally best to assume the presence of infection and treat aggressively.

Table 23.1 Compartmental Anatomy of the Foot | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Information is gathered to put a foot wound and the likelihood of infection into context. A focused history includes the history of any current or previous foot ulcers and their management. A history of new purulent drainage or swelling raises concern for infection. Any degree of foot pain is suspicious for infection. The degree to which

a patient may notice pain is dependent on the baseline degree of neuropathy affecting the foot, so the absence of pain obviously does not eliminate the likelihood of infection. A history of any known foot trauma is elicited in addition to the history of any events that may have caused foot trauma not appreciated by the patient, including longer distance walks or trips and new shoes. In certain areas of the country, freshwater and saltwater exposure may predispose to particularly aggressive soft tissue infections. The baseline functional status of the patient is also to be assessed at this early stage.

a patient may notice pain is dependent on the baseline degree of neuropathy affecting the foot, so the absence of pain obviously does not eliminate the likelihood of infection. A history of any known foot trauma is elicited in addition to the history of any events that may have caused foot trauma not appreciated by the patient, including longer distance walks or trips and new shoes. In certain areas of the country, freshwater and saltwater exposure may predispose to particularly aggressive soft tissue infections. The baseline functional status of the patient is also to be assessed at this early stage.

Figure 23.2 The compartments of the foot. See Table 23.1 for details. |

The presence of the usual systemic symptoms of infection, including fever, chills, and diaphoresis, is also to be elicited. Patients with diabetes, however, may frequently present with more subtle systemic symptoms such as poor appetite, hyperglycemia, general malaise, or “just not feeling right.” Sometimes, these subtle systemic signs can be present in patients with diabetes who have foot wounds that are otherwise not very suspicious for infection.

A focused physical examination also puts the likelihood of foot infection in context. First, any ulcers or wounds are identified and characterized. Structural foot deformities common in the diabetic foot, including prominent metatarsal heads, hallux valgus, or midfoot collapse (Charcot neuroarthropathy), are also noted, as ulcers are very often located over the bony prominences associated with these abnormalities. A formal assessment for neuropathy could be done with a monofilament; although its presence would not change acute management, it can be an important risk factor to address for offloading in the short term and for reducing the risk of reulceration in the long term. Finally, a vascular examination is performed by feeling for pulses at the femoral, popliteal, ankle, and pedal levels.

Many local and systemic signs may denote the presence of a foot infection. These signs may be similar to the signs of infection in other locations and in patients without diabetes. Like the symptoms of infection, though, it is frequently the case that the

physical signs may be more subtle in the diabetic foot. Blanching erythema—denoting cellulitis—and edema are perhaps the two most common signs. As with pain, the presence of tenderness on examination is variable depending on the degree of sensory neuropathy that is present. Fluctuance and/or crepitus strongly suggest infection of subcutaneous soft tissues. Foul odor is suspicious as well, but somewhat less specific as it can denote superficial colonization or necrotic debris only. The typical markers of a systemic inflammatory response, including fever, tachycardia, hypotension, and leukocytosis, signal the presence of infection. An unexplained hyperglycemia that is atypical for a given patient is also to be interpreted as a sign of infection. If diabetic patients with foot ulcers or other foot wounds present with these systemic symptoms or signs of infection, a foot infection is to be assumed as the etiology until proven otherwise.

physical signs may be more subtle in the diabetic foot. Blanching erythema—denoting cellulitis—and edema are perhaps the two most common signs. As with pain, the presence of tenderness on examination is variable depending on the degree of sensory neuropathy that is present. Fluctuance and/or crepitus strongly suggest infection of subcutaneous soft tissues. Foul odor is suspicious as well, but somewhat less specific as it can denote superficial colonization or necrotic debris only. The typical markers of a systemic inflammatory response, including fever, tachycardia, hypotension, and leukocytosis, signal the presence of infection. An unexplained hyperglycemia that is atypical for a given patient is also to be interpreted as a sign of infection. If diabetic patients with foot ulcers or other foot wounds present with these systemic symptoms or signs of infection, a foot infection is to be assumed as the etiology until proven otherwise.

Laboratory testing is to be done to establish a baseline and to look for other systemic signs of infection but with the understanding that normal laboratory results do not rule out a foot infection. Specific attention is given to low serum sodium bicarbonate, hyperglycemia, leukocytosis, and a left-shift (elevated proportion of bands) or elevated neutrophil percentage. A glycosylated hemoglobin (Hgb A1C) level may help establish a baseline and identify the need for more intensive outpatient glucose management. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels are obtained as a baseline.

A three-view series of foot x-rays (anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique) is useful for patients presenting with a foot infection. The presence of any of the following abnormalities are noted:

Chronic bony deformities of the foot, including those as listed above (majority of patients)

Obvious radiographic signs of osteomyelitis (common); these might include:

Cortical disruption/irregularity

Bony fragmentation (sequestrium)

New bone formation secondary to infection (involucrum)

Obvious signs of a joint space infection or erosion of the joint capsule; this may be manifest as a joint subluxation, dislocation, or supranormal range of motion (uncommon)

Air within soft tissues; physical signs of soft tissue infection will generally be noted where air is seen, but it is good practice to ensure any areas with soft tissue air are addressed at the time of the operation (uncommon)

Metallic or other radiopaque foreign bodies (rare)

MRIs or PET–CTs can be helpful in identifying osteomyelitis in cases when there are few or no signs of an associated soft tissue infection and findings on plain radiographs are lacking or unimpressive, but these imaging tests are very rarely needed as modalities to identify soft tissue infections.

Making the Decision to Operate

The decision of whether to operate on a patient with a foot infection is based on the surgeon’s assessment of whether drainable infection of any soft tissue structures other than epidermis (cellulitis) is present. The physical examination is the primary modality for making this assessment. Patients with no physical examination signs other than a limited area of cellulitis (blanching erythema extending <2 cm from the edge of a foot ulcer) can be classified as having a mild foot infection. These patients can be managed with oral antibiotics and close follow-up. Moderate foot infections—denoted by the presence of fluctuance, drainage, cellulitis >2 cm from the ulcer edge—denote infection of deeper soft tissue structures. These local findings accompanied by two or more signs of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome classify a foot infection as severe. With very few exceptions, patients with moderate and severe foot infections go promptly to the operating room for operative drainage.

It should be noted that none of the above-listed signs of infection—including those of systemic sepsis—represent a contraindication to operative drainage and efforts at limb preservation. Indeed, even septic shock need not be an absolute indication for a

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree