LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Learning Objectives

The student will be able to distinguish the acute and chronic forms of rhinitis and sinusitis in terms of their etiologies, histologic appearance, and resolution.

The student will be able to enumerate the common neoplastic diseases of the sinuses and nasopharynx and the frequency of benign versus malignant growth.

The student will be able to describe the range of disease types and severities that may involve the larynx, including the vocal chords and upper trachea, and when neoplastic, the likelihood of their progression to malignancy and metastasis.

Given their proximity to the environment, it is not surprising that the nasal cavities, sinuses, oropharynx, and trachea are all sites for infectious, inflammatory, and neoplastic diseases. As detailed in Chaps. 2 and 10, much of the lung’s conducting zone is well constructed to warm, humidify, and cleanse the inspiratory gas stream while maintaining physical barriers to aspiration events during eating, drinking, and speech. This chapter will focus on diseases that bear directly on respiratory function and pulmonary medicine rather than provide a compendium of all illnesses that might properly be considered the clinical domain of otolaryngology. Students are encouraged to consult adjoining chapters in this book for more specific details regarding anatomical landmarks, histologic configurations, and regional host defense mechanisms.

DISEASES OF THE NOSE, SINUSES, AND NASOPHARYNX

Inflammatory diseases are the most common disorders of the nose and its accessory paranasal sinuses. Rhinitis, or inflammation of the nasal mucosa, may be either infectious or allergic in its etiology. Nasal and sinus infections are usually viral in origin, particularly with adenoviruses, echoviruses, and rhinoviruses. Macroscopically, the affected areas appear red and swollen and may express copious watery exudates, all of which narrow or occlude nasal air passages and increase dynamic upper airway resistance. The histologic presentation is of respiratory mucosal edema, often with inflammatory cell infiltrates. Secondary bacterial infections are common in this setting, in which case neutrophilic influx and purulence are prominent. Uncomplicated cases of acute rhinitis normally resolve in 5-7 days in the immunocompetent host, although sequential infection of deeper airways can occur. As for viral and bacterial infections of the lung parenchyma, treatment options for rhinitis vary from curative to palliative depending upon the pathogen.

Allergic rhinitis, or hay fever, is caused by IgE-mediated reactions to any of the numerous allergens that are known to affect specific individuals. As many as 20% of the American public is affected by such seasonal disease, with the most common irritants as in asthma being plant pollens, fungi, animal dander, and insect droppings (Chap. 21). In such settings, there is also marked mucosal edema and redness of the affected nasal passages, while histologically the inflammatory infiltrates are often distinctly eosinophilic in composition. Nasal polyps are focal, usually non-neoplastic protrusions that commonly arise in the setting of such chronic rhinitis; they may be up to 3-4 cm in greatest dimension. Polyps are often asymptomatic and only found during routine physical exam. Alternatively, they may present with complaints of persistent rhinorrhea (runny nose), noisy breathing, and snoring. Histologically, the polyp is often covered by an intact respiratory epithelium that overlies a markedly edematous connective tissue stroma, usually with mucoid hyperplasia and cyst formation visible, as well as chronic inflammatory cell infiltrates (Fig. 33.1). Persistent polyps can become infected, even as they encroach upon airway lumens and impair sinus drainage. Medical treatment is primarily with nasal or oral corticosteroids, with surgical excision the best option for patients in whom such medical interventions fail.

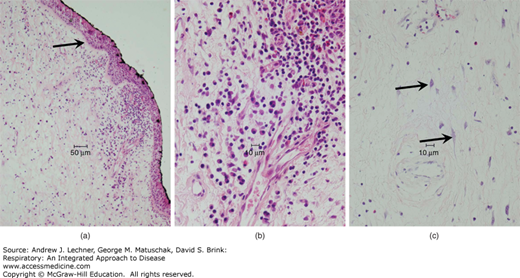

FIGURE 33.1

Nasal inflammatory polyp. (a) At low power, the polyp shows respiratory epithelium overlying a thickened basement membrane (arrow) and edematous stroma with an inflammatory infiltrate. (b) At high power, the inflammatory infiltrate is seen to be composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and scattered eosinophils. (c) Deeper in the polyp, inflammation is less severe, and edema dominates the morphology; some inflammatory polyps show fibroblast atypia (arrows), occasionally mimicking the appearance of neurons.

Acute sinusitis usually results from normal oropharyngeal flora causing inflammation and edema of the sinus mucosa. Obstruction of sinus outflow may cause empyema or lead to formation of a mucocele, a localized mucus accumulation in the absence of bacterial colonization. Indeed, diabetics can develop mucormycosis, often a life-threatening fungal sinusitis. The progression of acute sinusitis to chronic sinusitis is common, particularly with repeated exposure to a causative agent, in the immunosuppressed population, and in patients with anatomical anomalies like deviated nasal septa that block sinus drainage. Such chronic sinusitis (Fig. 33.2) may become superimposed with bacterial infection or become complicated by meningitis, osteomyelitis, orbital cellulitis, or cavernous vein thrombosis. Patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis often show nasal as well as intrapulmonary disease, in which there are microscopic findings of vasculitis, geographic necrosis, histiocyte accumulation, granulomatous inflammation, and epithelial ulceration. Chronic sinusitis is a presenting symptom in Kartagener syndrome due to defective ciliary clearance mechanisms, along with bronchiectasis and situs inversus.

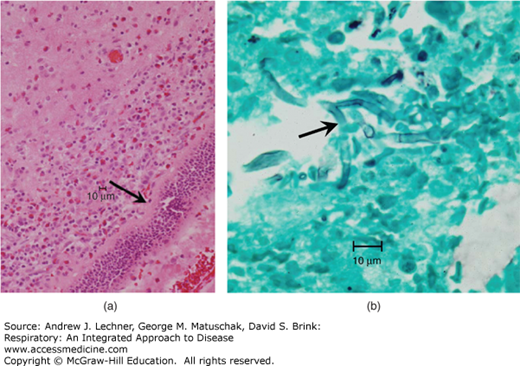

FIGURE 33.2

Sinusitis. (a) In this example of sinusitis, thickening of the basement membrane is apparent (arrow) typical of many chronic inflammatory processes involving mucosa. Here, the dominance of eosinophils in the inflammatory infiltrate is suspicious for allergic fungal sinusitis. (b) GMS staining identifies septate hyphae (arrow), morphologically consistent with Aspergillus species.

Necrotizing lesions of the nasal passages and sinuses may arise from several of the etiologies described above, notably those that reflect actual or potential systemic diseases, like mucormycosis and Wegener’s granulomatosis. Focal necrosis of these regions can also occur as a consequence of adjacent superimposed bacterial infection, tumor-related granulomatous inflammation, and some neoplastic processes involving other leukocytes, including natural killer cells.

Inflammation of the oropharynx and its associated lymphoid tissues causes pharyngitis and tonsillitis, respectively. As mentioned above, these often follow chronologically and anatomically from antecedent upper respiratory infections with rhinoviruses, adenoviruses, influenza, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). As for the nasal passages and sinuses, the pharynx becomes red and swollen with edematous mucosa and pseudomembranous exudates. Follicular tonsillitis is common and painful, with physical exam showing enlarged reddened tonsils covered with pinpoint exudates that adhere to or appear to be emerging from tonsillar crypts. Superinfection is common with β-hemolytic Streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus, whose late sequelae can produce rheumatic fever and glomerulonephritis (Chaps. 26 and 40).

Sinonasal papillomas are benign neoplasms that arise from the sinonasal mucosa and most commonly present in adult men whose primary complaint is nasal obstruction. Histologically, they consist of proliferating squamous epithelium among other mucin- positive cells. As such, their cytologic atypia is not impressive, and the cells as a group are usually mature and well-differentiated. The presence of human papilloma virus (HPV) types 6 and 11 is detected in many sinonasal papillomas. Papillomas that originate in the nasal septum are most common; most often these have an exophytic growth pattern, emerging mushroom-shaped from the mucosa with a core of connective tissue [Fig. 33.3(a)]. Papillomas that originate from the middle meatus or middle or inferior turbinates are of an inverted type with an endophytic growth pattern that resembles plant root tubercles penetrating the underlying stroma [Fig. 33.3(b)]. Such inverted papillomas recur at a high rate if not completed excised surgically, and they are also the type most often associated with coexisting or subsequent carcinomas, in 3%-10% of patients.

FIGURE 33.3

In sinonasal papilloma, the epithelium is stratified squamous. (a) In the everted/exophytic pattern, the epithelium covers finger-like projections of loose connective tissue. (b) Papillomata arising from the lateral wall typically show an inverted/endophytic growth pattern, with inward growth of the epithelium into the stroma, occasionally mimicking invasive carcinoma.