and Alessandra Cancellieri2

(1)

Department of Radiology, Bellaria Hospital, Bologna, Italy

(2)

Department of Pathology, Maggiore Hospital, Bologna, Italy

Radiology | Luciano Cardinale Edoardo Piacibello Giorgia Dalpiaz |

Adenocarcinoma | Adenocarcinoma | Page 164 |

AE-IPF | Acute exacerbation of IPF | Page 166 |

AEP | Acute eosinophilic pneumonia | Page 168 |

AIP | Acute interstitial pneumonia | Page 170 |

ARDS | Acute respiratory distress syndrome | Page 172 |

CEP | Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia | Page 174 |

COP | Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia | Page 176 |

DAH | Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in WG | Page 178 |

DIP | Desquamative interstitial pneumonia | Page 180 |

Drug toxicity | Amiodarone-induced lung disease | Page 182 |

FES | Fat embolism syndrome | Page 184 |

Infection, acute (PJP) | PJP | Page 186 |

Infection, chronic (TB) | TB | Page 188 |

LP | Lipoid pneumonia | Page 192 |

MALToma | Mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue lymphoma | Page 194 |

Metastases, aerogenous | Metastases, aerogenous | Page 196 |

PAP | Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis | Page 198 |

PE, alveolar | Pulmonary edema, alveolar | Page 200 |

Adenocarcinoma

Definition

Adenocarcinoma has surpassed squamous cell carcinoma as the leading histologic type, accounting for 30 % of all cases of lung cancer. The new 2015 who classification provided the basis for a multidisciplinary approach emphasizing the close correlation among radiologic and histopathologic pattern of lung adenocarcinoma. The term “bronchioloalveolar carcinoma” has been eliminated, introducing the concepts of adenocarcinoma in situ (ais) and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (mia) and the use of descriptive predominant patterns in invasive adenocarcinomas (lepidic, acinar, papillary, solid, and micropapillary patterns). Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma is the new definition for mucinous bronchioloalveolar carcinoma.

Travis WD (2015) The 2015 World Health Organization classification of lung tumors: impact of genetic, clinical and radiologic advances since the 2004 classification. J Thorac Oncol 10(9):1243

High-Resolution CT: HRCT

Key Signs

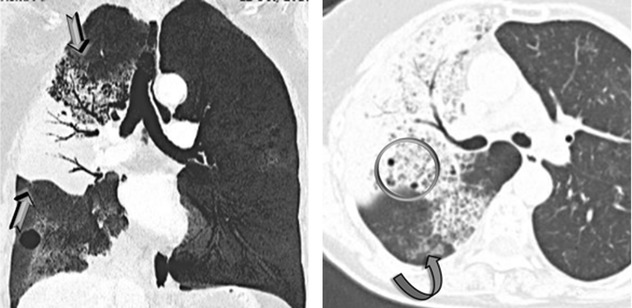

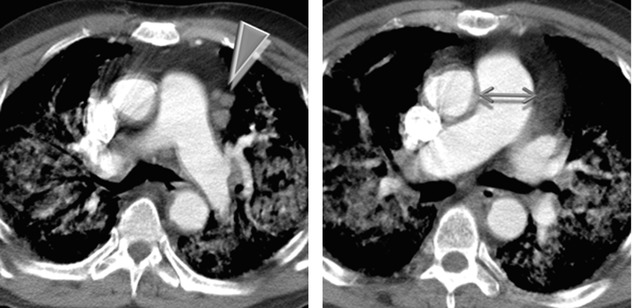

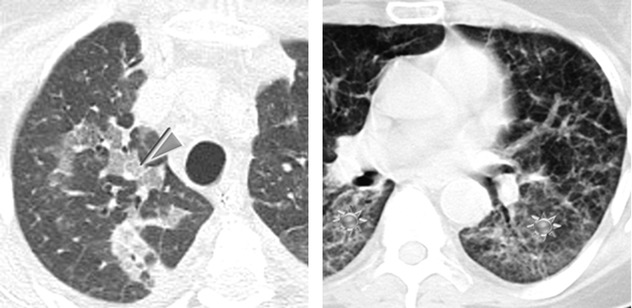

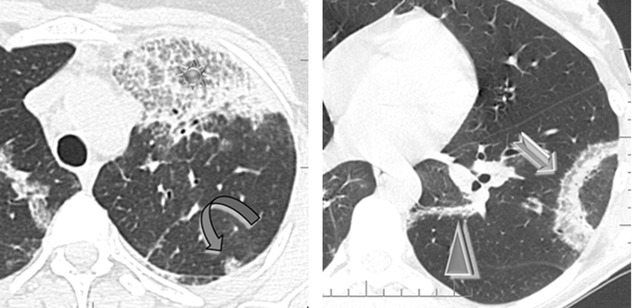

Patchy areas of non-resolving consolidation (➨) with possible halo sign and often with air bronchogram or air-filled cystic spaces (bubble-like lucencies) ( )

)

Patchy non-resolving ground-glass opacity ( )

)

Distribution

Unilateral or bilateral, usually asymmetrical, and often patchy. The consolidation may be segmental or may involve an entire lobe or lung. Often peripheral distribution. Possible lower lung predominance.

Bubble-like lucencies are small lucencies inside consolidations (pseudocavitation). They can be formed by a valve mechanism by bronchiolar obstruction or by desmoplastic bronchiolar traction or paracicatricial emphysema. Also, lucency can result from spared pulmonary lobules (please also refer to Bubble-like lucencies in the “Case-Based Glossary with Tips and Tricks”).

The stretching, sweeping, and widening of branching air-filled bronchi within an area of consolidation on computed tomography (CT) favor the diagnosis of cancer instead of pneumonia.

Areas of ground-glass attenuation and consolidation often have straight and angulated margins, suggesting demarcation by interlobular septum at the margin of the secondary pulmonary lobule. A halo sign may be present around the consolidation due to lepidic growth.

Patsios D (2007) Pictorial review of the many faces of bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma. Br J Radiol 80(960):1015

Gaeta M (1999) Radiolucencies and cavitation in bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: CT-pathologic correlation. Eur Radiol 9(1):55

Ancillary Signs

Low-density consolidation with angiogram sign on contrast-enhanced CT (►)

Crazy paving ( )

)

Centrilobular or feeding vessel nodules due to the aerogenous or hematogenous intrapulmonary spread of the tumoral cells ( )

)

Consolidation and/or nodules with halo sign (lepidic growth)

Non-parenchymal Signs

Pleural effusion (10 %)

Lymph node enlargement

Usually, inflammatory angiogram sign, pseudocavitation, and crazy paving are more frequent in adenocarcinoma than in consolidation.

CT angiogram sign may be visible because fluid and mucus produced by the tumor are of low attenuation if CT is performed with contrast infusion. This sign may be also observed in bacterial pneumonia, lipid pneumonia, pulmonary lymphoma, and metastasis of gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas (please also refer to Angiogram sign in the “Case-Based Glossary with Tips and Tricks”).

Diffuse lung involvement may represent multifocal origin, endobronchial spread of tumor from primary focus, hematogenous metastases, or a combination of these.

Jung JI (2001) CT differentiation of pneumonic-type bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma and infectious pneumonia. Br J Radiol 74(882):490

Piacibello E (2015) Lung cancer: one issue, many faces. ECR C-2202

Course

Slow progression with continuous growth of neoplastic cells (lepidic growth).

Intrapulmonary discontinuous spread of neoplastic cells through airspaces and airways; the discontinuous foci may be seen close to primary tumor as satellite foci or at distance, including the contralateral lung (aerogenous metastases).

The discontinuous spread of neoplastic cells through lymphatic vessels can cause intrapulmonary metastasis along the lymphatic vessels or locoregional metastasis to the lymph nodes (lymphatic metastases).

The discontinuous spread of neoplastic cells through blood vessels can cause intrapulmonary and systemic metastases (hematogenous metastases).

Gaikwad A (2014) Aerogenous metastases: a potential game changer in the diagnosis and management of primary lung adenocarcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 203(6):W570

Warth A (2015) Prognostic impact of intra-alveolar tumor spread in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 39:793

Kadota K (2015) Tumor spread through air spaces is an important pattern of invasion and impacts the frequency and location of recurrences after limited resection for small stage I adenocarcinomas. J Thorac Oncol 10:806

Acute Exacerbation of IPF (AE-IPF)

Definition

The criteria for acute exacerbation (AE) of IPF include an unexplained worsening of dyspnea within 1 month, evidence of hypoxemia as defined by worsened or severely impaired gas exchange, new radiographic infiltrates, and an absence of an alternative cause of disease. Surgical lung biopsy or even surgical procedures in organs other than the lungs may also trigger AE. The annual incidence of AE-IPF is typically reported at 5–15 %. The histologic findings consist of diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) or, less commonly, prominent organizing pneumonia (OP) superimposed on the UIP pattern.

AE-IPF, accelerated phase

Collard HR (2007) Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176(7):636

High-Resolution CT: HRCT

Key Signs

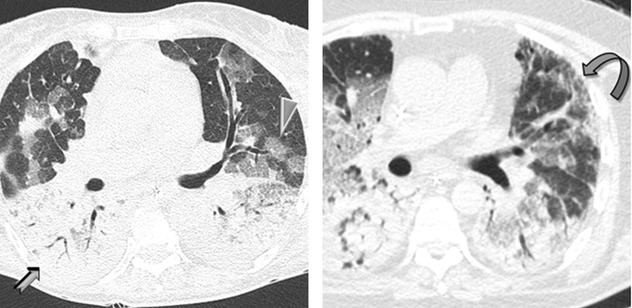

Diffuse ground-glass opacity (GGO) is the dominant sign.

Sometimes also consolidations can be visualized.

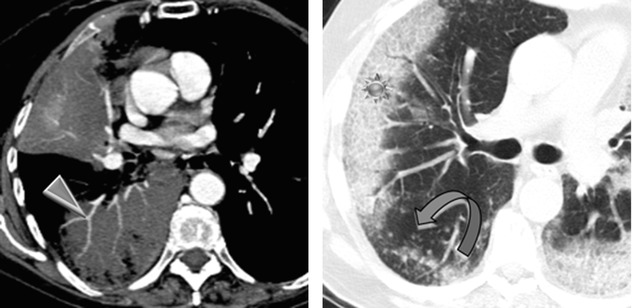

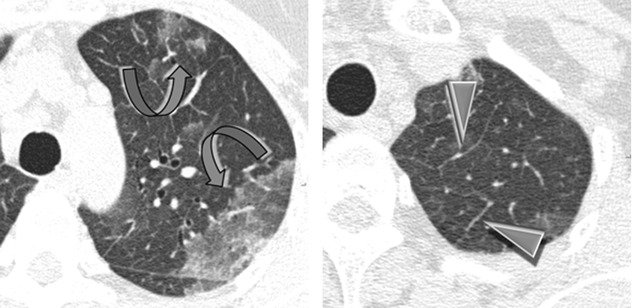

Signs of fibrosing lung disease ( ): fibrosing subpleural reticulation, traction bronchiectases, and honeycomb change typical of UIP pattern.

): fibrosing subpleural reticulation, traction bronchiectases, and honeycomb change typical of UIP pattern.

Distribution

Often bilateral and diffuse with possible multifocal and peripheral distribution. The consolidations tend to involve mainly the dorsal half of the lung.

Acute exacerbation is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion. Differential diagnoses include concomitant infection (such as P. jirovecii pneumonia or cytomegalovirus infection), pulmonary edema due to left ventricular failure, pulmonary embolism, and pneumothorax.

When it is necessary to exclude the diagnosis of pulmonary thrombo-embolic disease with a CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA), intravenous contrast enhancement increases the attenuation of the background lung parenchyma, which can complicate the evaluation of whether the lungs are of abnormally increased attenuation. In this situation, interspaced HRCT sections should be obtained prior to the acquisition of the contrast-enhanced CTPA.

Akira M (2008) Computed tomography findings in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 178(4):372

Lloyd CR (2011) High-resolution CT of complications of idiopathic fibrotic lung disease. Br J Radiol 84(1003):581

Ancillary Signs

Crazy paving

Non-parenchymal Signs

Lymph node enlargement (►).

Pulmonary arterial hypertension: enlargement of the main ( ) and proximal pulmonary arteries; however, normal-sized pulmonary arteries do not exclude the diagnosis.

) and proximal pulmonary arteries; however, normal-sized pulmonary arteries do not exclude the diagnosis.

Antoniou KM (2013) Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiration 86(4):265

Luppi F (2015) Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a clinical review. Intern Emerg Med 10(4):401

Course

Patients with acute exacerbation have a poor prognosis with mortality exceeding 50 % despite therapy.

Survival may be related to the degree of CT involvement. The extent of disease is a more important determinant of outcome than the distribution of disease.

AE represents the most frequent cause of rapid deterioration requiring hospitalization of IPF patients.

AE have been reported in ILDs other than IPF, including nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP), and ILD associated with connective vascular disease (CVD), particularly rheumatoid arthritis.

Fujimoto K (2012) Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: high-resolution CT scores predict mortality. Eur Radiol 22(1):83

Park IN (2007) Acute exacerbation of interstitial pneumonia other than idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 132(1):214

Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia (AEP)

Definition

Acute eosinophilic pneumonia is an acute severe febrile illness associated with rapidly increasing respiratory failure. The diagnosis is based on clinical findings and the presence of markedly elevated numbers of eosinophils in BAL fluid. The majority of cases are idiopathic; occasionally, it may result from drug reaction or toxic inhalation. Patients respond rapidly to high doses of corticosteroids, usually within 24–48 h. The principal histologic finding in AEP is diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) associated with interstitial and alveolar eosinophilia.

AEP

Philit F (2002) Idiopathic acute eosinophilic pneumonia: a study of 22 patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166(9):1235

High-Resolution CT: HRCT

Key Signs

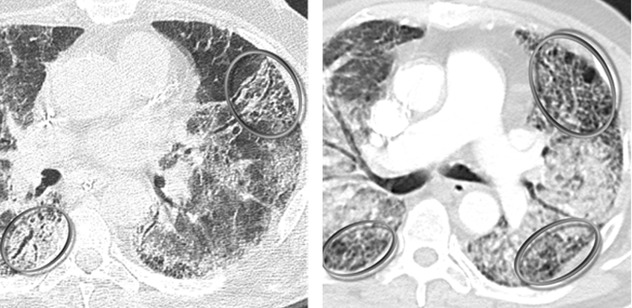

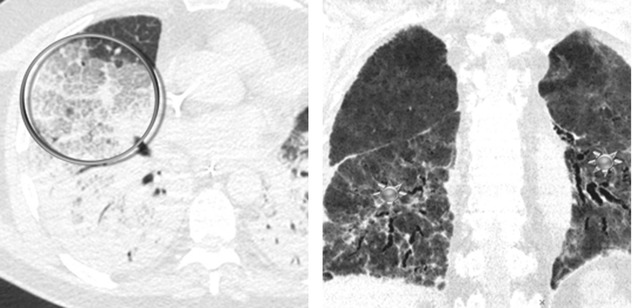

Areas of ground-glass opacity (GGO) ( )

)

Smooth interlobular septal thickening (►)

Distribution

Bilateral, patchy in a random or peripheral distribution, no zonal predominance

Given that initial peripheral blood eosinophil counts are usually normal, therefore developing a clinicoradiologic differential diagnosis for AEP is often difficult.

The radiologic differential diagnosis for AEP includes hydrostatic pulmonary edema (PE), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP), and atypical bacterial or viral pneumonia. In contrast to these forms, patients with AEP usually have a dramatic response to corticosteroids, with rapid resolution of clinical signs and symptoms and radiographic abnormalities.

Obadina ET (2013) Acute pulmonary injury: high-resolution CT and histopathological spectrum. Br J Radiol 86 20120614

Jeong YJ (2007) Eosinophilic lung diseases: a clinical, radiologic, and pathologic overview. Radiographics 27(3):617

Ancillary Signs

Possible crazy paving (➨) and consolidations

Poorly defined centrilobular nodules and thickening of bronchovascular bundles

Non-parenchymal Signs

Small pleural effusion is present in the majority of patients (►), absent cardiomegaly.

Peripheral blood eosinophilia is often absent in contrast to chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Eosinophilia on BAL (>25 % eosinophils) or lung biopsy is the key for diagnosis; however, eosinophils are exquisitely sensitive to corticosteroids and may disappear from blood-stream and BAL fluid within few hours after administration of corticosteroids.

Cottin V (2016) Eosinophilic lung diseases. Clin Chest Med 37:535

Daimon T (2008) Acute eosinophilic pneumonia: thin-section CT findings in 29 patients. Eur J Radiol 65(3):462

Course

Complete response to corticosteroids: no relapse after discontinuation of corticosteroids

Acute Interstitial Pneumonia (AIP)

Definition

Acute interstitial pneumonia is a term used for an idiopathic form of acute lung injury characterized clinically by acute respiratory failure with bilateral lung infiltrates and histologically by diffuse alveolar damage (DAD). The acute, exudative phase shows edema, hyaline membranes, and acute interstitial inflammation. In the subacute, proliferative (organizing) phase, the fibroblast proliferation mainly becomes prominent. In the chronic, fibrotic phase, 2 weeks or more after the injury, there is progressive fibrosis. The acute presentation and the histologic features are identical with those of DAD, so AIP has also referred to as idiopathic DAD. The average age at presentation is 50–60 years. It has no gender predominance and no association with cigarette smoking. It is classified among the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias.

AIP, Hamman–Rich syndrome, idiopathic DAD

The general term idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs) includes various diseases. The major IIPs include idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP), acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP), respiratory bronchiolitis–interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD), and cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP). Rare idiopathic interstitial pneumonias include idiopathic lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP) and idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (PPFE).

Travis WD (2013) An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188(6):733

High-Resolution CT: HRCT

Key Signs

The HRCT findings are strictly correlated to the pathologic phases of DAD:

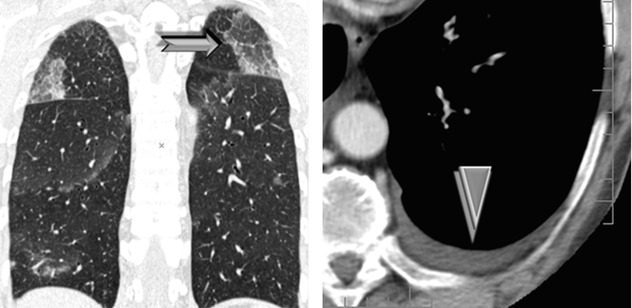

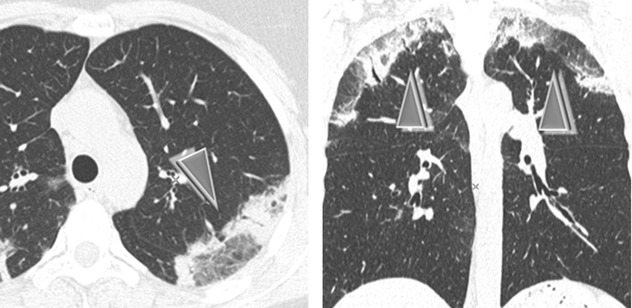

Acute or exudative phase (first week): extensive ground-glass opacities (➨) and/or airspace consolidation with air bronchogram (7)

Proliferative phase (second week): within areas of GGO and consolidation, the appearance of distortion of the architecture, volume loss, traction bronchiectases ( ), and bronchiolectases

), and bronchiolectases

Distribution

Patchy (geographic) or confluent and tends to involve mainly the dependent lung

Traction bronchiolectases or bronchiectases within areas of increased attenuation on HRCT scan is a sign of progression from the exudative to the proliferative and fibrotic phase.

Patients with greater extent of ground-glass attenuation or airspace consolidation without traction bronchiectases or bronchiolectases on HRCT scan have been shown to have a better prognosis than patients with greater extent of increased attenuation with traction bronchiectases or bronchiolectases.

Mukhopadhyay S (2012) Acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP): relationship to Hamman-Rich syndrome, diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Semin Respir Crit Care Med 33(5):476

Ichikado K (2014) High-resolution computed tomography findings of acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute interstitial pneumonia, and acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 35(1):39

Ancillary Signs

Smooth septal thickening

Crazy paving (7)

Non-parenchymal Signs

Absent

Although the HRCT findings of AIP and ARDS reflect the presence of DAD and therefore overlap, patients with AIP are more likely to have a symmetric lower lobe distribution of abnormalities and a greater prevalence of honeycombing.

Tomiyama N (2001) Acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute interstitial pneumonia: comparison of thin-section CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr 25(1):28

Course

The prognosis is poor, with the majority of studies reporting a mortality ranging from 50 to 100 %.

In the surviving patients, HRCT may show mild residual fibrotic features (fibrosing reticulation, architectural distortion, fibrotic GGO) (please see the figure above ) and possible mild honeycombing.

) and possible mild honeycombing.

Akira M (1999) Computed tomography and pathologic findings in fulminant forms of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. J Thorac Imaging 14:76

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)

Definition

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a syndrome characterized by diffuse lung injury and progressive dyspnea and hypoxemia over a short time. The clinical criteria of acute lung injury or ARDS defined by the American-European Consensus Conference in 1994 have been revised as the Berlin definition in 2012. According to this latest definition, the diagnosis is based on the onset of hypoxemia and of bilateral chest opacities within 1 week of a known risk factor. From the radiological point of view, the presence of bilateral opacities remains one of the hallmarks for diagnosis. However, it was explicitly recognized that these findings could be detected by computed tomography (CT) instead of radiography.

Pathologically, ARDS is characterized by diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) and evolves over 2 or 3 weeks through exudative, fibroproliferative phases.

ARDS

ARDS Definition Task Force (2012) Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA 307(23):2526

High-Resolution CT: HRCT

Key Signs

The HRCT findings closely correlate to pathologic phases of DAD:

Acute or exudative phase (first week): HRCT may be normal in the early phase of DAD but is usually abnormal within 12 h with extensive ground-glass opacities (7) and/or airspace consolidation with air bronchogram (➨).

Proliferative phase (second week): distortion of the architecture, volume loss, fibrosing reticulation, traction bronchiectases or bronchiolectases ( ), and honeycombing represent signs of early fibrosis.

), and honeycombing represent signs of early fibrosis.

Distribution

Bilateral, diffuse with a gravity-dependent gradient, with larger areas of consolidation in the posterobasal regions, as a result of compressive gravitational forces

Ichikado K (2014) High-resolution computed tomography findings of acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute interstitial pneumonia, and acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 35(1):39

Zompatori M (2014) Overview of current lung imaging in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Eur Respir Rev 23(134):519

Ancillary Signs

Reticular opacities

Crazy paving ( )

)

Non-parenchymal Signs

Small pleural effusion (less representative than decompensated heart failure)

In the early stage of disease (exudative phase), reticular opacities and crazy paving correspond histologically to alveolar collapse adjacent to interlobular septa and subsequent organization or correspond to edematous thickening.

In the proliferative and fibrotic phase (see Course below), reticulation is fibrosis (see figure with  above) with associated distorted parenchyma.

above) with associated distorted parenchyma.

above) with associated distorted parenchyma.

above) with associated distorted parenchyma.The differential diagnosis of ARDS includes cardiogenic pulmonary edema, acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP), diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), and acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP); however, the most challenging differential diagnosis is still between ARDS and cardiogenic edema, especially in the acute phase.

Ellen L (2014) Detection of fibroproliferation by chest high-resolution CT scan in resolving ARDS. Chest 146(5):1196–1204.

Course

In surviving patients in the later stages, CT may usually demonstrate progressive regression of opacities with complete healing of lesions.

A rarer evolution is progressive lung fibrosis (fibrotic phase): fibrosing reticulation, architectural distortion, fibrotic GGO (please see the figure above ), and possible mild honeycombing.

), and possible mild honeycombing.

Early signs of barotrauma often correspond to interstitial emphysema and subpleural cystic airspaces. Subsequently, imaging studies can demonstrate the development of pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax (often hypertensive in mechanically ventilated patients), and subcutaneous emphysema.

Superimposed cardiac failure, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, ventilator-induced lung injury, malposition of tubes, central venous catheters, and drainages or other conditions may suddenly worsen the clinical evolution.

Obadina ET (2013) Acute pulmonary injury: high-resolution CT and histopathological spectrum. Br J Radiol 86(1027):20120614

Desai SR (1999) Acute respiratory distress syndrome: CT abnormalities at long-term follow-up. Radiology 210:29

Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia (CEP)

Definition

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) is an idiopathic condition characterized by an abnormal accumulation of eosinophils in the lungs. The clinical course lasts more than 1–3 months. Most patients are middle aged, and approximately 50 % have asthma.

CEP is almost always associated with increased numbers of eosinophils on BAL fluid and in peripheral blood. Radiologically, CEP is characterized by peripheral unresolving or migrating pneumonia.

CEP

Alam M (2007) Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia: a review. South Med J 100(1):49

High-Resolution CT: HRCT

Key Signs

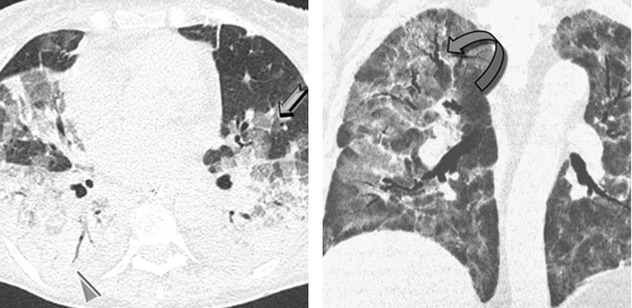

Non-resolving airspace consolidations and ground-glass opacities are often associated (7) with changing in location over a matter of weeks.

Distribution

Peripheral in almost all cases (so-called reverse batwing sign or photographic negative shadow of pulmonary edema), mainly the upper lobes, patchy or confluent

In CEP, the distribution of opacities is identical to that in Löffler syndrome, although in the latter, the lung opacities are self-limited. Also in COP, alveolar sarcoidosis, infarcts, and contusions consolidations can be seen in peripheral airspace (please also refer to Reverse batwing sign in the “Case-Based Glossary with Tips and Tricks”).

Spontaneous migration of the opacities can be present in both CEP and OP.

Yeong YJ (2007) Eosinophilic lung diseases: a clinical, radiologic, and pathologic overview. Radiographics 27(3):617

Ebara H (1994) Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia: evolution of chest radiograms and CT features. J Comput Assist Tomogr 18(5):737

Ancillary Signs

Crazy paving ( )

)

Low-density (subsolid) nodules (20 %) with hazy contours (20 %) ( )

)

Reversed halo sign (atoll sign), rarely (➨)

Linear bandlike opacities seen during resolution (7)

Non-parenchymal Signs

Pleural effusion (<10 %)

Mediastinal lymph node enlargement

The diagnosis of eosinophilic pneumonia relies on both characteristic clinical imaging features and demonstration of alveolar eosinophilia. Lung biopsy is generally not necessary for the diagnosis of eosinophilic pneumonia.

An identical appearance to that of CEP may be seen in patients who have simple pulmonary eosinophilia (Löffler syndrome) and in patients with Churg–Strauss syndrome (CSS).

An identical appearance of peripheral consolidations can be seen in OP. In this disease, the lesions are not only confined to the lung periphery but are also bronchocentric and often predominate in the lower lobes. In addition, a macronodular appearance or a pattern of round opacities is frequent. Septal thickening or parenchymal bands are uncommon.

Sano S (2009) Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia: a case report and review of the literature. Cases J 2:7735

Cottin V (2012) Eosinophilic lung diseases. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 32(4):557

Course

Response to steroid treatment is generally dramatic with improvement of symptoms within 24 h and clinical and radiological remission within 3 weeks.

Progression to diffuse lung fibrosis is rare.

The disease tends to recur frequently after discontinuation of steroid treatment (75 %).

During regression, consolidation tends to disappear centrifugally and may be temporarily followed by subpleural curvilinear bands. If the disease is left untreated, the opacities may progressively increase in number and even migrate.

Oyama Y (2015) Efficacy of short-term prednisolone treatment in patients with chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Eur Respir J 45(6):1624

Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia (COP)

Definition

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) is the idiopathic form of organizing pneumonia. OP is a well-known histopathologic pattern characterized by loose plugs of proliferating fibroblasts and myofibroblasts within the alveolar ducts and airspaces, accompanied by varying degrees of bronchiolar involvement. COP is classified among the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs). Patients with COP typically present with a 2–4-month history of nonproductive cough, low-grade fever, malaise, and shortness of breath. The mean age of presentation is 50–60 years.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree