and Alessandra Cancellieri2

(1)

Department of Radiology, Bellaria Hospital, Bologna, Italy

(2)

Department of Pathology, Maggiore Hospital, Bologna, Italy

Radiology | Nicola Sverzellati Mario Silva |

EHE | Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma | Page 114 |

FB | Follicular bronchiolitis | Page 116 |

Hemorrhage | Endometriosis | Page 118 |

HP, subacute | Hypersensitivity pneumonitis, subacute | Page 120 |

HTL | Hot tub lung | Page 122 |

Infection, miliary TB | Tuberculosis, miliary | Page 124 |

LCH, early | Langerhans cell histiocytosis, early | Page 126 |

LIP | Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia | Page 128 |

Metastases, hematogenous | Metastases, hematogenous | Page 130 |

MPC | “Metastatic” pulmonary calcification | Page 132 |

PCH | Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis | Page 134 |

RB-ILD | Respiratory bronchiolitis-ILD | Page 136 |

Sarcoidosis | Sarcoidosis | Page 138 |

Silicosis | Silica-induced pneumoconiosis | Page 144 |

Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma (EHE)

Definition

Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma is a rare neoplasm (prevalence <1/1,000,000) of vascular endothelial origin with low-to-intermediate malignant potential that can arise in the lung, liver, bones, and soft tissue. Pulmonary epithelioid hemangioendothelioma mainly affects young women (median age of onset is 36 years) and is usually asymptomatic.

EHE

Shao J (2014) Clinicopathological characteristics of pulmonary epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: a report of four cases and review of the literature. Oncol Lett 8(6):2517

High-Resolution CT: HRCT

Key Signs

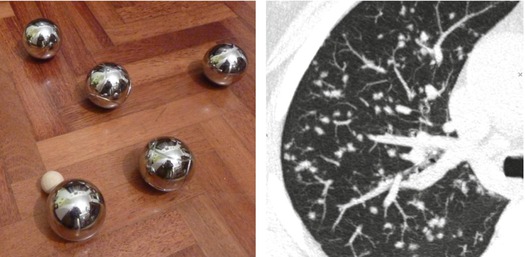

Multiple small solid ( ) and subsolid pulmonary nodules (<1 cm), also with irregular margins. More rarely, nodules can be up to 5 cm.

) and subsolid pulmonary nodules (<1 cm), also with irregular margins. More rarely, nodules can be up to 5 cm.

Distribution

Mostly bilateral, however, unilateral distribution was reported in 25 % of cases. Nodules are frequently subpleural (e.g., < 2 cm from the pleura), with perivascular distribution, namely, adjacent to small- and medium-sized vessels and bronchi.

The nodules detected in EHE usually show clear boundaries, although in case of infiltration of vessels and bronchi, the margins can be irregular or ill-defined.

EHE is a neoplasm of mesenchymal origin characterized by the presence of multiple, usually bilateral, small nodules, mainly distributed in the subpleural space; the main differential diagnosis is represented by metastatic lesions.

Liu K (2014) The computed tomographic findings of pulmonary epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Radiol Med 119(9):705

Kim M (2015) Pulmonary epithelioid hemangioendothelioma misdiagnosed as a benign nodule. World J Surg Oncol 13:107

Ancillary Signs

Punctate calcification and ossification inside the nodules may be observed.

Reticulonodular opacities are a rare pattern of presentation.

Non-parenchymal Signs

Thickening of the pleural layers (►) is a consequence of the pleural invasion, despite pleural effusion being quite rare.

Enlargement of mediastinal lymph nodes ( ).

).

Bone metastases are usually osteolytic (➨) and show homogeneous enhancement after injection of contrast agent.

Small nodules are usually negative at 18 F-FDG-PET, while the bigger ones may show an uptake (SUV ≥ 2.5), thus suggesting more malignant behaviors.

Sardaro A (2014) Pulmonary epithelioid hemangioendothelioma presenting with vertebral metastases: a case report. J Medl Case Reports 8:201

Sakamoto N (2005) High resolution CT findings of pulmonary epithelioid hemangioendothelioma unusual manifestations in 2 cases. J Thorac Imaging 20:236–238

Course and Complications

The prognosis is extremely variable, from long/indolent to cases of partial spontaneous regression. Therefore, life expectancy may range from 1 to 30 years.

A wedge or anatomical resection is possible in case of a single lesion, while multiple nodules are treated with chemotherapy.

Mizuno Y (2011) Pulmonary epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 59:297–300

Follicular Bronchiolitis (FB)

Definition

Follicular bronchiolitis (FB) represents a nonneoplastic pulmonary lymphoid disorder characterized by lymphoid hyperplasia of the bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT). Hyperplastic lymphoid follicles and well-defined reactive germinal centers distributed along bronchovascular bundles characterize the histological pattern of FB.

FB is mainly secondary to collagen vascular disease – CVD (particularly, rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren), AIDS, or hypersensitivity reaction – whereas the primary (idiopathic) form is rare. Follicular bronchiolitis usually affects middle-aged people. Dyspnea with insidious onset, cough, and weight loss are the main symptoms, which usually show insidious and unspecific onset.

FB

Tashtoush B (2015) Follicular Bronchiolitis: a literature review. J Clin Diagn Res 9(9):OE01

High-Resolution CT: HRCT

Key Signs

Small bilateral centrilobular nodules, usually 3 mm in size (diameter ranges 1–12 mm)

Nodules which mimic a tree-in-bud pattern (peribronchiolar distribution), more visible on MIP images (please see the sagittal MIP image below)

Distribution

The nodules are distributed throughout the lung, with possible slight basal predominance.

MIP image highlights the visibility and the profusion of the diffuse small nodules. The sagittal plane also confirms the centrilobular distribution of the nodules (nodules “pavid of pleura”).

FB seldom represents the sole abnormality on HRCT as it often coexists with other lung abnormalities (e.g., interstitial lung disease and other lymphoid tissue disorders).

FB overlaps imaging features of other types of bronchiolitis. Indeed, the radiological diagnosis is very difficult if not impossible without any knowledge of the clinical background (e.g., collagen vascular disease).

Pipavath SJ (2005) Radiologic and pathologic features of bronchiolitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 185(2):354

Kang EY (2009) Bronchiolitis: classification, computed tomographic and histopathologic features, and radiologic approach. J Comput Assist Tomogr 33(1):32

Ancillary Signs

Bronchial dilatation or bronchial wall thickening (►).

Lymphoid follicles in the bronchiolar wall narrow the bronchiolar lumen with obstruction to airflow variably associated with mosaic attenuation pattern on inspiratory CT; therefore, expiratory CT is granted to assess and quantify the air trapping.

Mild ground-glass opacity, mostly reflecting coexisting interstitial lung disease.

Cystic changes ( ).

).

Non-parenchymal Signs

Absent

Thin-walled cysts, randomly distributed and ranging from 3 mm to 1 cm, represent a finding also of lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP), which is itself associated with FB and represents a pathophysiological continuum of lymphocytic infiltration from hyperplasia of BALT to cellular expansion of the interstitium with fibrosis.

The cystic pattern associated with Sjögren’s syndrome typically shows septa within cysts with heterogeneous size, parenchymal thinning into the so-called dissolving lung appearance (mainly basal and perivasal), and frequent association with ground-glass opacities and nodules.

Gupta N (2015) Diffuse cystic lung disease. Part II. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 192(1):17

Gupta N (2016) Diffuse cystic lung disease as the presenting manifestation of Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Am Thorac Soc 13(3):371

Howling SJ (1999) Follicular bronchiolitis: thin-section CT and histologic findings. Radiology 212(3):637

Course and Complications

Follicular bronchiolitis secondary to connective tissue diseases or AIDS are usually treated with pharmaceutical approach for the underlying disease.

Burgel PR (2013) Small airways diseases, excluding asthma and COPD: an overview. Eur Respir Rev 22(128):131

Carrillo J (2013). Lymphoproliferative lung disorders: a radiologic-pathologic overview. Part I: reactive disorders. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 34(6):525

Hemorrhage in Endometriosis

Definition

Thoracic endometriosis syndrome (TES) encompasses a variety of symptoms and signs determined by migration of endometriosis foci through diaphragmatic defects (pleural implant) or microembolization from pelvic veins (parenchymal implant). TES is associated with pelvic endometriosis, with median age of presentation about 35 years (approximately 5 years later than pelvic symptoms onset). Catamenial pneumothorax and hemoptysis reflect pleural and pulmonary involvement, respectively. In parenchymal involvement, recurrent alveolar damage is caused by episodes of alveolar hemorrhage during the menstrual cycle. Pulmonary nodules represent the rarest form of presentation (6 %).

TES, Catamenial hemorrhage

Joseph J (1996) Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: new observations from an analysis of 110 cases. Am J Med 100(2):164

Alifano M (2006) Thoracic endometriosis: current knowledge. Ann Thorac Surg 81:761

High-Resolution CT: HRCT

Key Signs

Low-density (subsolid) nodules (snowflake nodules)

Small solid nodules with halo sign ( )

)

Distribution

Bilateral. The right lung is involved in about 70 % of nodular presentation.

Halo sign refers to a ground-glass opacity that surrounds circumferentially pulmonary solid nodules due to hemorrhagic involvement. It may present both in hemorrhagic and nonhemorrhagic diseases (please also refer to halo sign in the chapter “Nodular Pattern” and in the “Case-Based Glossary with Tips and Tricks”).

Temporal heterogeneity of parenchymal findings is the CT hallmark of this rare presentation of TES. In the acute phase, atelectasis can be seen as consequence of endobronchial clots. In the chronic phase, band-like opacities reflect linear fibrosis from chronic hemorrhage.

Rousset P (2014) Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: CT and MRI features. Clin Radiol 69(3):323

Huang Q (2015) Clinical and radiographic characteristics in pulmonary endometriosis: based on five cases. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 42(3):336

Ancillary Signs

Macronodules (➨).

Focal ground-glass opacities and consolidation reflecting alveolar filling from periodic bleeding ( ) (image courtesy of Angelo Carloni, Terni).

) (image courtesy of Angelo Carloni, Terni).

Cavitation can happen in nodules and pulmonary hematomas.

Non-parenchymal Signs

Catamenial and non-catamenial pneumothorax

Catamenial hemothorax with pleural thickening, notably right-sided

Pulmonary endometriosis is a rare presentation of TES which shows nodules on HRCT. The diagnosis is achieved on clinical ground; in particular catamenial hemoptysis and cyclical wax and wane of HRCT findings is hallmark of this rare abnormality. Pneumothorax and hemothorax are the most frequent symptoms of TES; they can coexist and are variably associated with the pulmonary involvement.

Pleural and diaphragmatic hemorrhagic lesions may be diagnosed by MRI, which shows typical signal features.

Korom S (2004) Catamenial pneumothorax revisited: clinical approach and systematic review of the literature. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 128(4):502

Haga T (2014) Thoracic endometriosis-related pneumothorax distinguished from primary spontaneous pneumothorax in females. Lung 192(4):583

Cassina PC (1997) Catamenial hemoptysis. Diagnosis with MRI. Chest 111(5):1447

Course and Complications

Nodules may vary in size according with the menstrual cycle, up to resolution in some cases.

Patients can report hemoptysis, which may be controlled by either surgical (e.g., VATS) or medical treatment (e.g., hormone therapy); chemoembolization of bronchial artery may be considered among therapeutic options.

Pneumothorax is better treated by pleuroscopy and pleurodesis, rather than with medical therapy. Nevertheless, relapse is common despite either treatment.

Legras A (2014) Pneumothorax in women of child-bearing age: an update classification based on clinical and pathologic findings. Chest 145(2):354

Kervancioglu S (2008) Bronchial artery embolization in the management of pulmonary parenchymal endometriosis with hemoptysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 31(4):824

Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis (HP), Subacute

Definition

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis is caused by inhalatory exposure to organic particles, which engage an exaggerated immune response at the level of small airways and alveoli in susceptible individuals. Recognized antigens include proteins from different species (e.g., animals, insects, bacteria, and protozoa), fungi, and low-molecular-weight chemical compounds. The radiological findings are influenced by the stage of the disease.

The subacute form of hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) typically presents a prevalent nodular pattern.

HP, extrinsic allergic alveolitis (EAA – this term has been largely used in the past, currently it is obsolete).

Clinical presentation may be also acute or chronic (please refer to HP, Chronic in the chapter “Fibrosing Diseases”).

Selman M (2012) Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: insights in diagnosis and pathobiology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186(4):314

Spagnolo P (2015) Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: a comprehensive review. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 25(4):237

High-Resolution CT: HRCT

Key Signs

Low-density centrilobular nodules (snowflake nodules) no larger than 5 mm

Lobular areas of air trapping ( )

)

Distribution

HP-related abnormalities are seen with homogeneous distribution to both lungs throughout the lung; although a mid-to-lower lung zone predominance has been variably reported.

Silva CI (2007) Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: spectrum of high-resolution CT and pathologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 188(2):334

Ancillary Signs

Patchy ground-glass opacity may be present, though more commonly observed in acute phase.

Headcheese sign with lobular air trapping easily visible on expiratory CT.

Cysts in up to 12 % of cases.

Non-parenchymal Signs

Pneumomediastinum can occur in case of subpleural cyst rupture.

The “headcheese sign” results as the combination of ground-glass opacity, decreased attenuation areas (reflecting air trapping at expiratory CT scanning), and normal lung. Please also refer this sign to the “Case-Based Glossary with Tips and Tricks”.

HRCT features of HP may overlap those of several disorders. Notably, the combination of features of infiltrative (ill-defined nodules and ground-glass opacity) and small airways disease (sporadic lobular areas of air trapping appearing as patches of black lung) may be useful for the differential diagnosis with RB-ILD. The distinction can usually be made also with knowledge of the smoking history.

HP has been described also in patients undergoing chemotherapy (e.g., docetaxel). Acute dyspnea and respiratory failure should prompt HRCT investigation. Discontinuation of chemotherapy and high-dose corticosteroid administration prevent worsening of the respiratory performance.

Genestreti G (2015) A commentary on interstitial pneumonitis induced by docetaxel: clinical cases and systematic review of the literature. Tumori 101(3):e92

Course and Complications

In the subacute phase, the nodules usually regress with removal from exposure.

Possible progression to the chronic form of HP. It is characterized by progressive fibrotic changes, with either UIP or NSIP pattern. Of note, air trapping and headcheese pattern should help in the differential between HP and idiopathic interstitial pneumonitis. At this stage, mixed restrictive and obstructive functional abnormalities are seen.

Elicker BM (2016). Multidisciplinary Approach to Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis. J Thorac Imaging;31(2):92

Definition

Hot tub lung (HTL) is a diffuse granulomatous lung disease affecting immunocompetent individuals, caused by inhalation of hot tub water containing nontuberculous mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). MAC is commonly found in natural water and tap water and is resistant to most water decontaminants. Moreover, whirlpool and jets in hot tubs drizzle hot vapor, which is an extremely favorable medium for MAC growth. A recent report mentions occupational associations among possible causes of HTL. There is debate whether HTL should be classified as an independent disease or it should be included among hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP), infections, or a crossing point of these two conditions. Of note, the histology of HTL shows the dominance of well-formed granulomas, as opposed to HP where interstitial inflammation is more represented. Granulomas in HTL can be randomly distributed in bronchioles, airspace, and interstitium.

According to the American Thoracic Society, HTL can be diagnosed by typical HRCT findings without histopathology, in case of subacute onset of symptoms (e.g., dyspnea, fatigue, low-grade fever, and unintentional weight loss) associated with hot tub exposure and positive mycobacterial culture from respiratory samples and water.

HTL

The pathogenesis of HTL consist in a hypersensitivity reaction toward mycobacterial cell wall antigens. The hypothesis of a hypersensitivity pneumonitis is supported by the complete recovery following antigen withdrawal and corticosteroid therapy.

Hanak V (2006) Hot tub lung: presenting features and clinical course of 21 patients. Respir Med 100(4):610

Fjällbrant H (2013) Hot tub lung: an occupational hazard. Eur Respir Rev 22(127):88

Cheung OY (2003) Surgical pathology of granulomatous interstitial pneumonia. Ann Diagn Pathol 7(2):127

Cancellieri A, Dalpiaz G (2010) Granulomatous lung disease. Pathologica 102(6):464

High-Resolution CT: HRCT

Key Signs

Small centrilobular low density (snowflake nodules) (please see the axial CT image below).

Possible tiny solid nodules randomly distributed (please see the sagittal and coronal MIP images below).

Ground-glass opacities may coexist with the nodules (please see all images below).

Distribution

Both nodules and ground-glass opacity are usually bilateral, homogeneously distributed in throughout the lungs.

The HRCT findings of HTL may overlap HP.

Hartman TE (2007) CT findings of granulomatous pneumonitis secondary to Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare inhalation: “hot tub lung”. AJR Am J Roentgenol 188(4):1050

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree