5

CHAPTER

![]()

Diffuse Alveolar Damage, Acute Interstitial Pneumonia

Diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) and its clinicopathologic counterpart, acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP), are reviewed in a separate chapter because they represent a unique manifestation of acute lung injury, and their pathologic changes cannot be pigeonholed into interstitial or airspace predominant categories.

TOPICS

Diffuse Alveolar Damage (DAD)

Diffuse Alveolar Damage (DAD)

Acute Interstitial Pneumonia (AIP)

Acute Interstitial Pneumonia (AIP)

DIFFUSE ALVEOLAR DAMAGE (DAD)

Diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) isa purely descriptive term for the spectrum of pathologic changes that follow acute lung injury. Most patients clinically manifest the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Usually, the cause of the lung injury is known, but when it cannot be identified, the resultant idiopathic condition is known as AIP. It is discussed in the subsequent section, “Acute Interstitial Pneumonia.”

Histologic Features

Hyaline membranes and/or fibroblast proliferation

Hyaline membranes and/or fibroblast proliferation

Epithelial hyperplasia and metaplasia, often with cytologic atypia

Epithelial hyperplasia and metaplasia, often with cytologic atypia

Small arterial thrombi

Small arterial thrombi

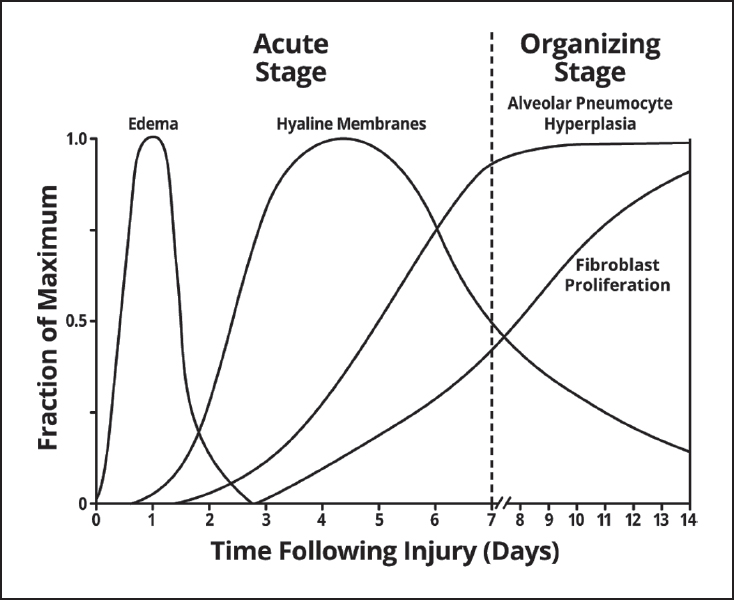

The pathologic changes in DAD comprise roughly two stages: acute (early), occurring within the first week or so following injury, and organizing (proliferative, later), occurring after a week or two. In reality, as illustrated schematically in Figure 5.1, there is no sharp division between the two stages because features of both are often present together in a given case. Nonetheless, the approximate time interval following injury can be estimated from the relative proportion of abnormalities present.

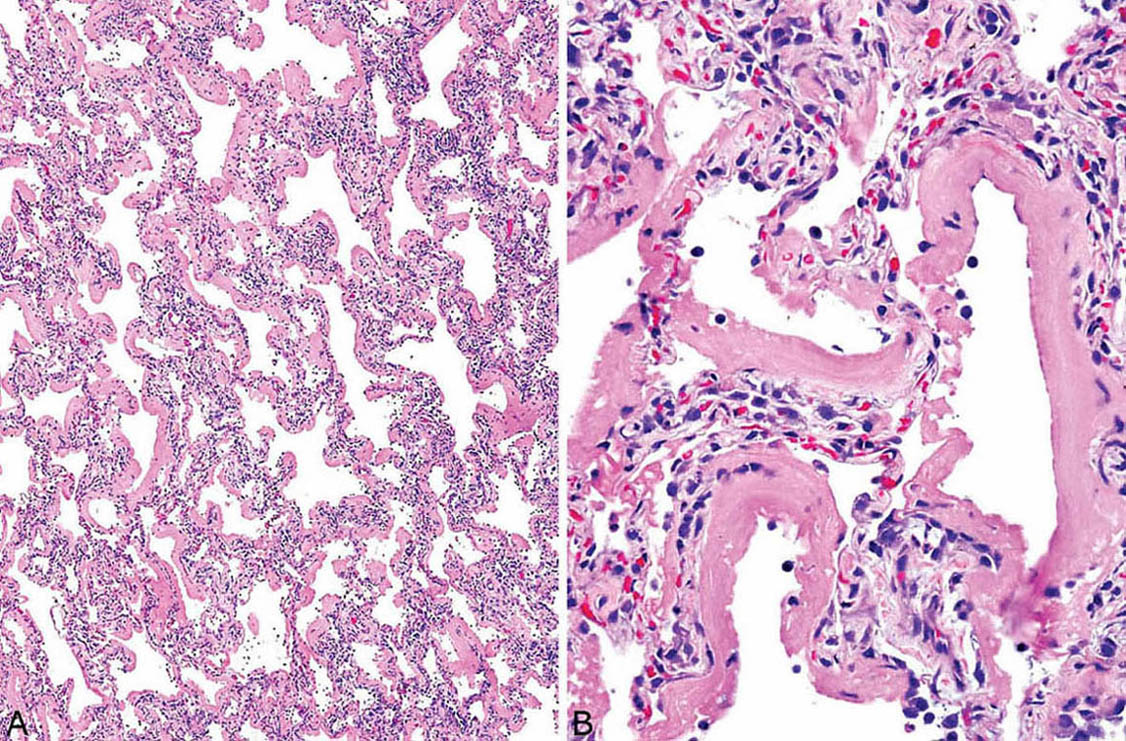

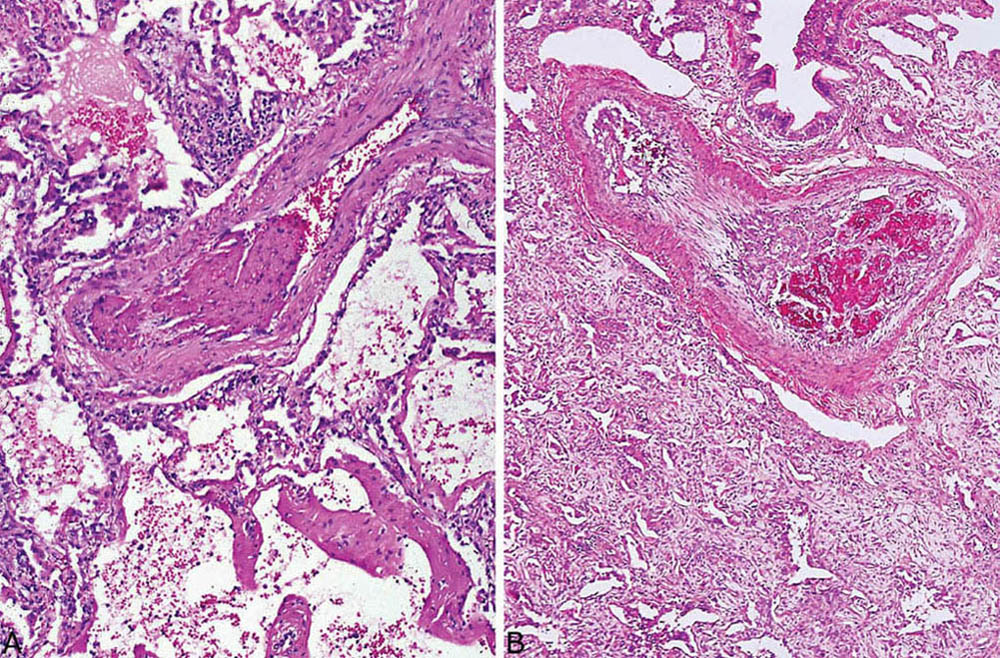

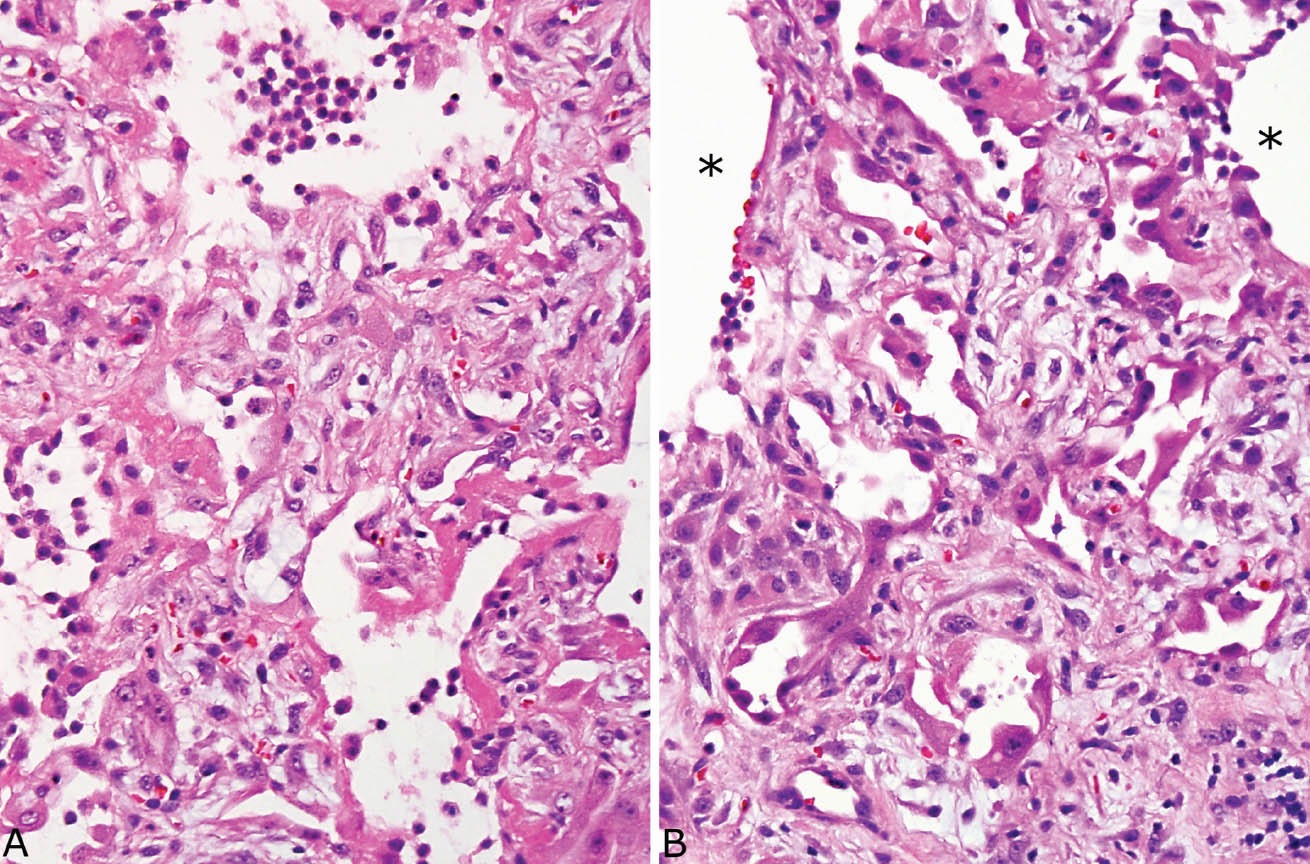

The histologic hallmark of the acute stage is the presence of hyaline membranes. Although edema, both interstitial and intra-alveolar, is the earliest change in DAD, edema is difficult to recognize in routine sections and to separate from biopsy-related artifactual changes. Hyaline membranes develop a day or so following injury and become most prominent in 3 or 4 days. They appear as glassy, eosinophilic structures within airspaces that are plastered along alveolar septa (Figure 5.2). They comprise a mixture of fibrin and other serum proteins and usually appear fairly homogeneous, although they sometimes contain scattered bare nuclei or other cellular debris. Remnants of edema fluid and fibrinous exudates as well as some nuclear debris may be seen in alveolar spaces, but intra-alveolar inflammation is scant if present at all (Figure 5.3).

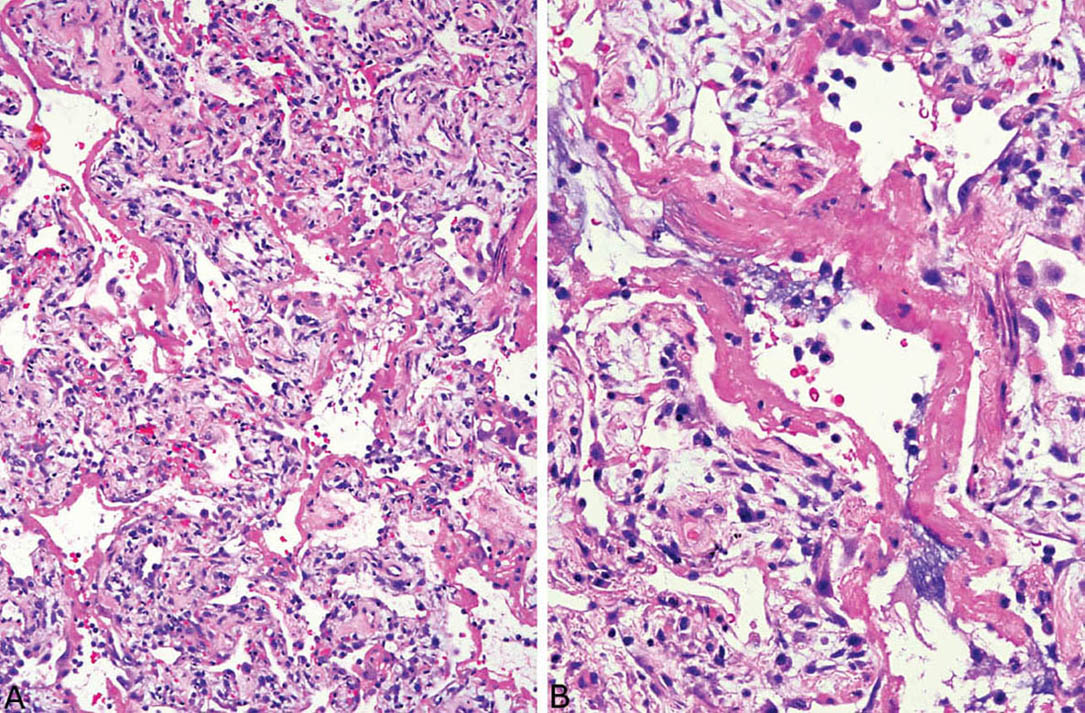

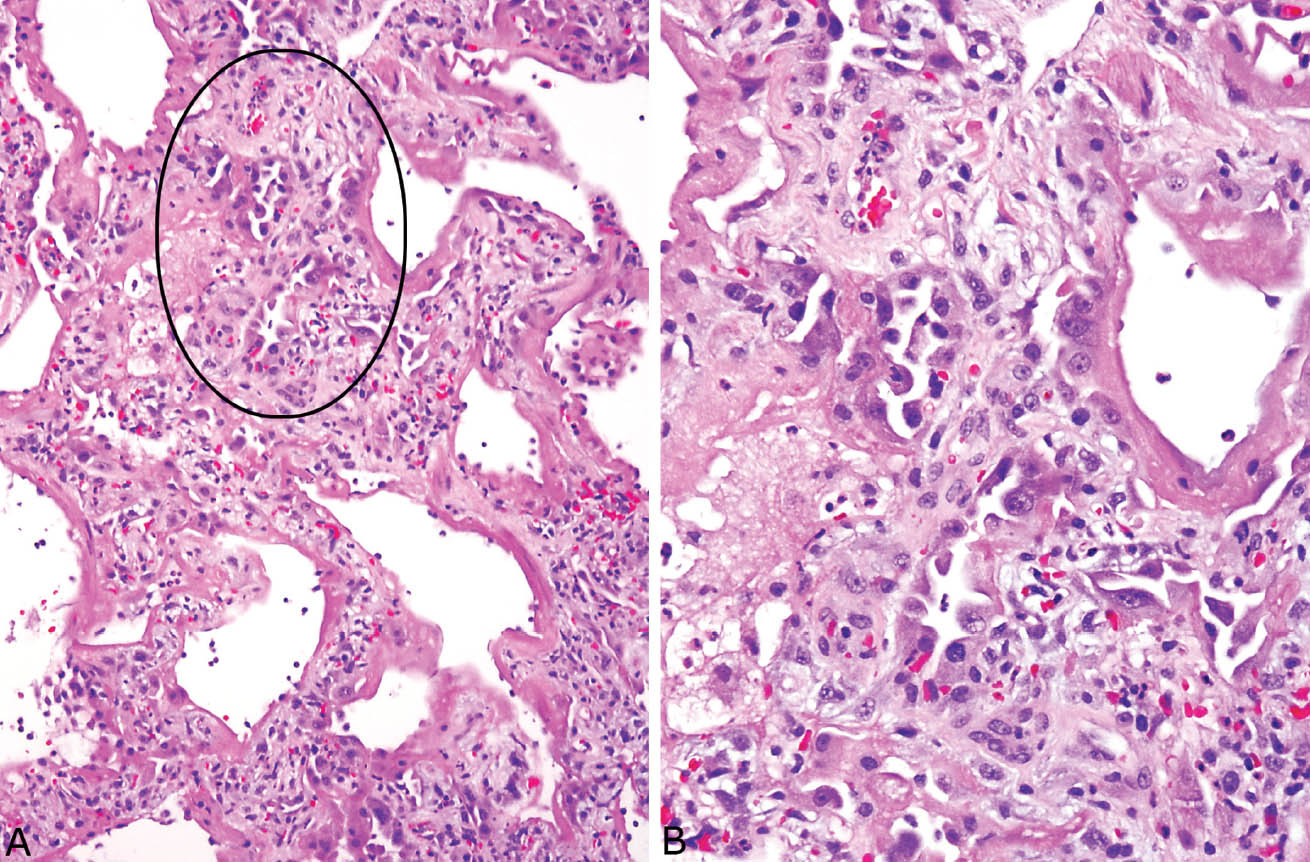

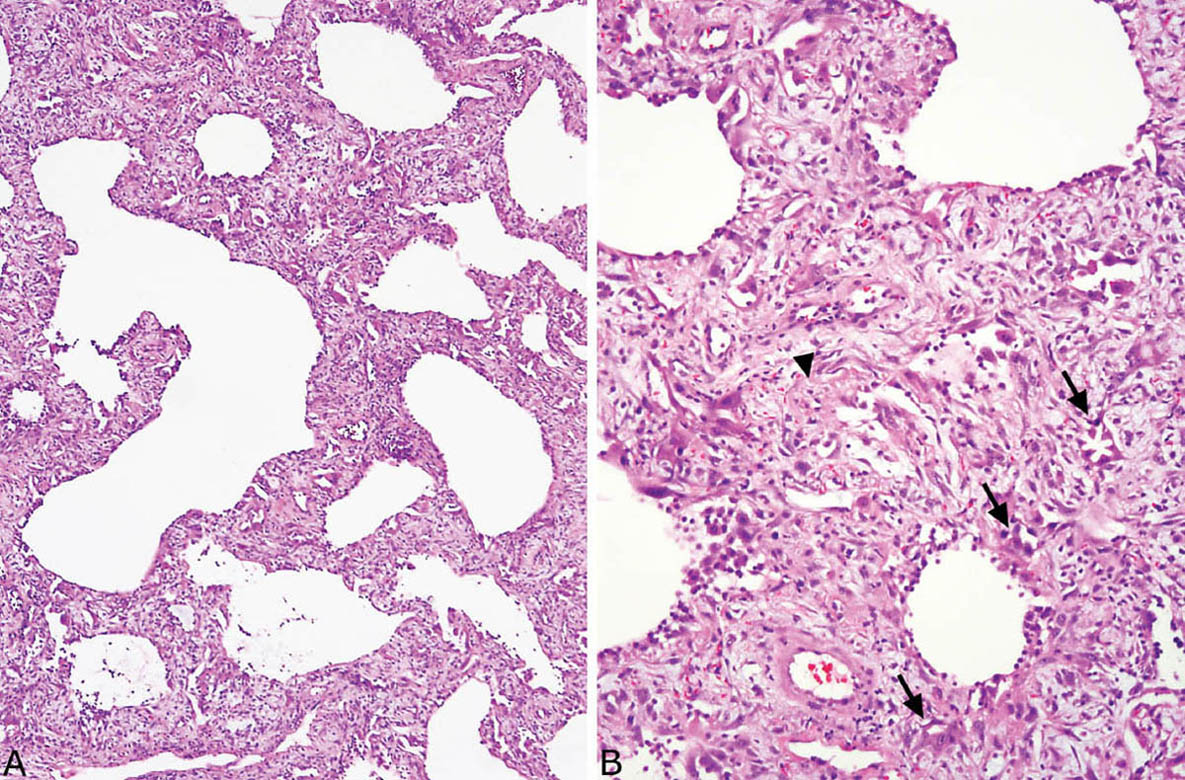

Alveolar septa are mildly thickened by edema or alveolar wall collapse. Occasional acute or chronic inflammatory cells may also be present within alveolar septa, but interstitial inflammation is usually not prominent. Alveolar pneumocyte hyperplasia begins after 3 to 4 days, and becomes most prominent after a week or so (Figure 5.4). Fibrin thrombi often undergoing organization are frequently found in small arteries in both acute and organizing stages, and they may be numerous (Figure 5.5).

FIGURE 5.1 Schematic representation of the time course of the pathologic changes in DAD. Note the overlapping spectrum of the changes over time. DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

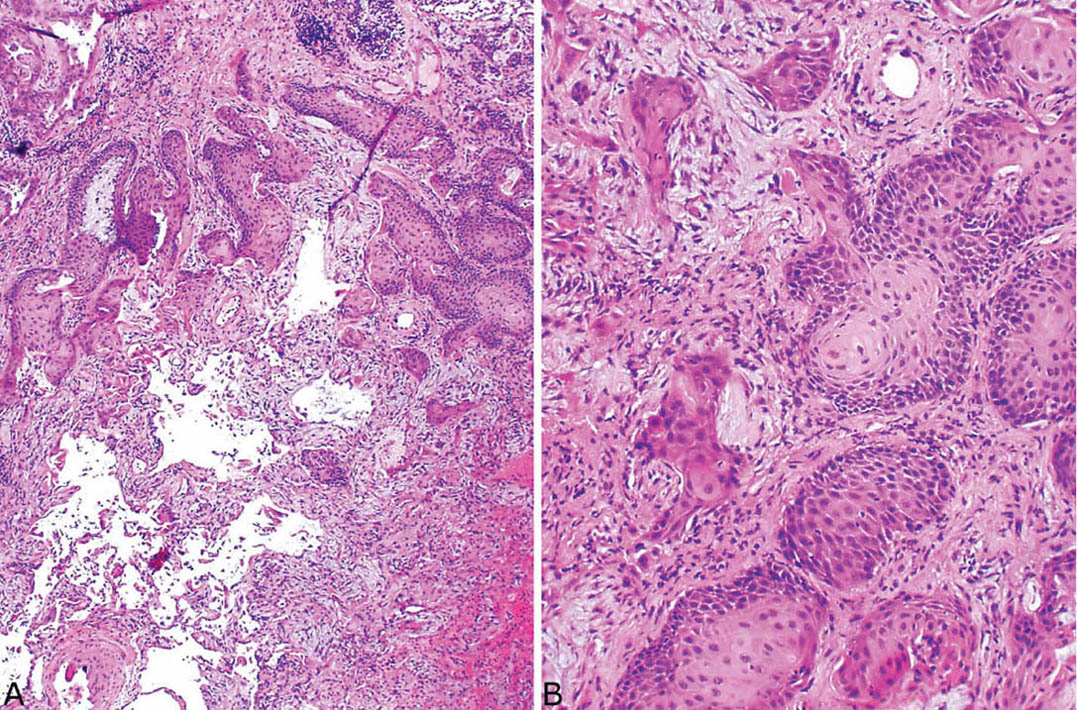

FIGURE 5.2 DAD, acute stage. (A) Low magnification showing prominent hyaline membrane formation along mildly thickened alveolar septa. (B) At higher magnification, the hyaline membranes appear homogeneous and eosinophilic with only scattered entrapped nuclear fragments. The alveolar septal thickening is due mainly to alveolar collapse. The appearance fits with injury occurring 3 to 4 days previously. DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

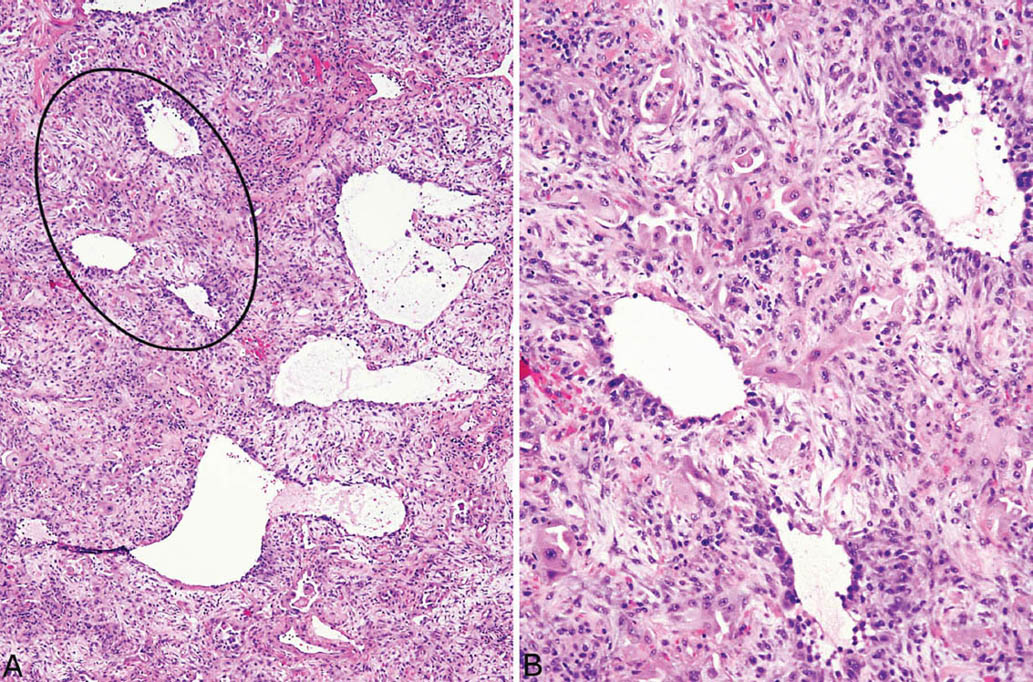

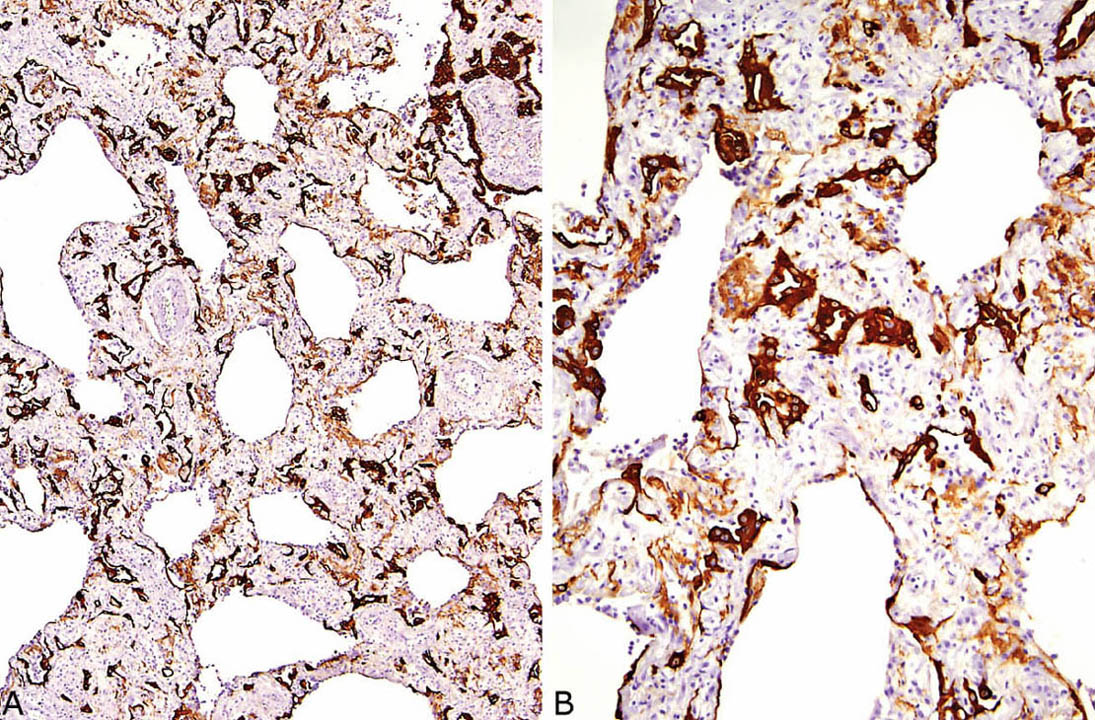

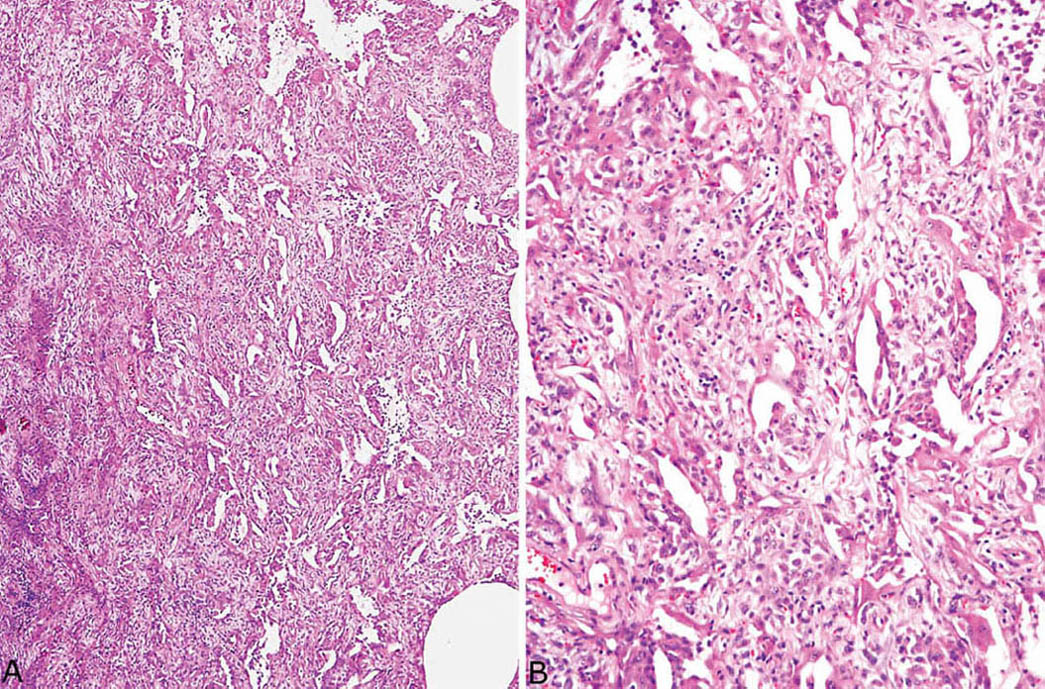

The organizing stage of DAD is a reparative response to the injury and is characterized by interstitial fibroblast and myofibroblast proliferation along with alveolar pneumocyte hyperplasia. At low magnification, the process is characterized by hypercellular, temporally uniform thickening of alveolar septa that varies from mild to marked (Figures 5.6 and 5.7). Spindle-shaped fibroblasts and myofibroblasts embedded within lightly staining, often myxoid stroma are prominent within the thickened alveolar septa and account for much of the cellularity. In addition to the spindled cells, remnants of entrapped, often collapsed alveoli lined by hyperplastic pneumocytes comprise a portion of the interstitial cellularity and contribute to the alveolar wall thickening. The entrapped pneumocytes can be highlighted with cytokeratin immunostaining, which shows more cells than appreciated on hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) stains (Figure 5.8). A mild chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate may be associated with the other changes but is usually a minor component, and collagen deposition is minimal. Remnants of hyaline membranes may still be seen along alveolar septa in places, but are not prominent (Figure 5.9). In advanced cases, the fibroblast proliferation may be so extensive that the parenchyma appears solid with only slit-like lumens of alveolar spaces remaining (Figure 5.10). As in the acute stage, fibrin thrombi are common in small arteries (Figure 5.5B).

FIGURE 5.3 DAD, acute stage. (A) In this example, hyaline membranes are plastered against alveolar septa that are thickened by edema, scattered mononuclear inflammatory cells, and a few fibroblasts. (B) At higher magnification, occasional pyknotic nuclei and cellular debris are seen within the hyaline membranes and in alveolar spaces. The appearance fits with injury occurring 5 to 7 days previously. DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

FIGURE 5.4 Alveolar pneumocyte hyperplasia in DAD. (A) At low magnification, hyaline membranes are seen lining thickened alveolar septa and there are areas of prominent alveolar pneumocyte hyperplasia (circle). These findings indicate injury occurring a week or more previously. (B) Higher magnification of the circled area shows the typical hobnail configuration of the hyperplastic alveolar pneumocytes, some of which are cytologically atypical. DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

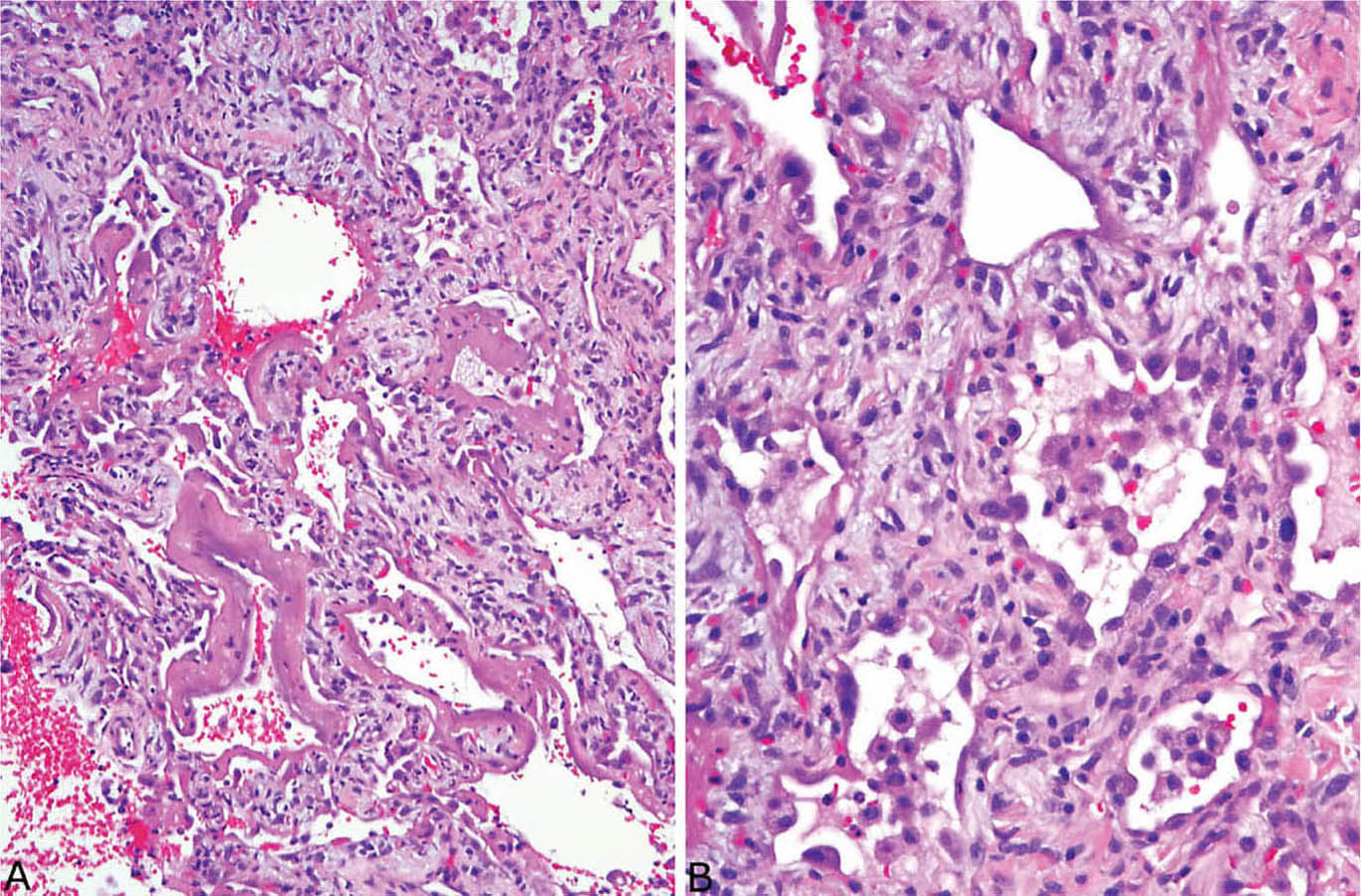

FIGURE 5.5 Thrombi in DAD. Recent and organizing thrombi are present in small arteries in cases of acute DAD (A) and organizing DAD (B). DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

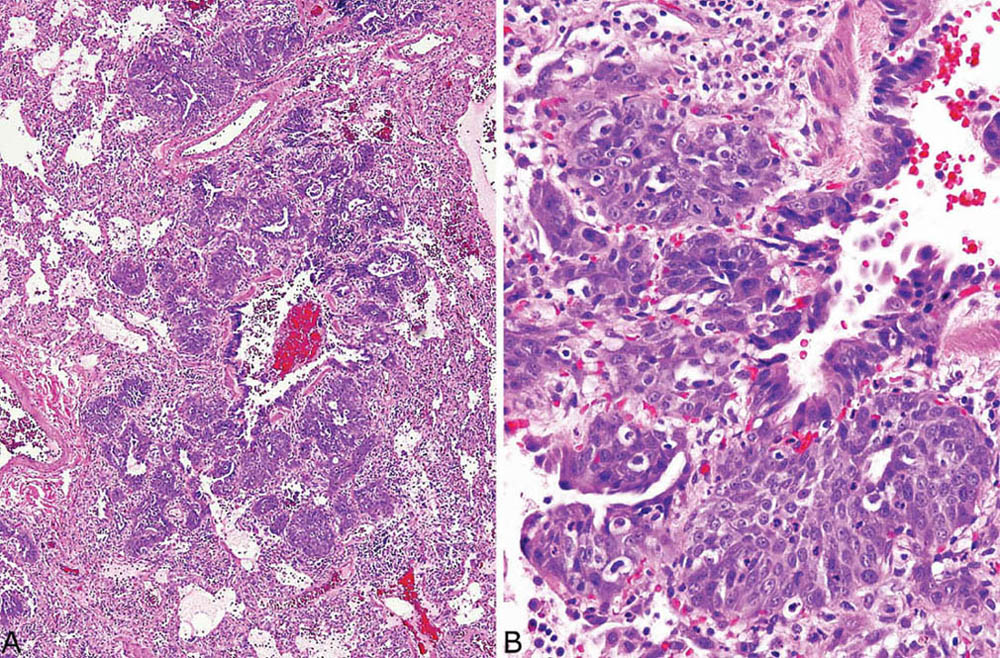

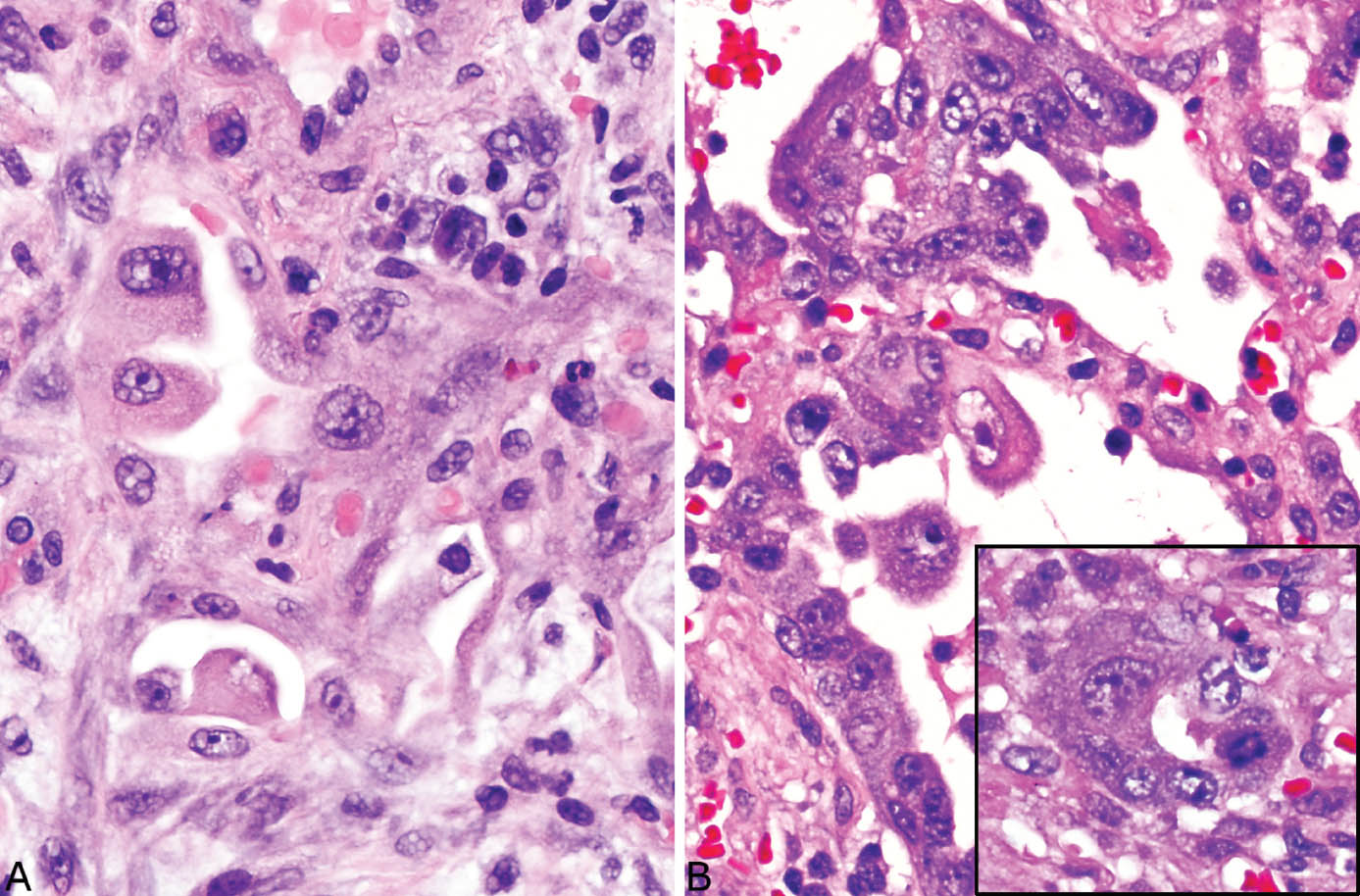

Epithelial hyperplasia is often prominent in the organizing stage and includes squamous metaplasia in and around bronchioles in addition to alveolar pneumocyte hyperplasia (Figures 5.4, 5.9B, and 5.11). Cytologic atypia is common in both the alveolar epithelium and the squamous metaplasia areas, and it may be severe. The hyperplastic lining cells are often enlarged, irregular, and hobnail shaped with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli, and they can cause false-positive cytology diagnoses (Figure 5.12). Mitotic figures are often present, and some may be atypical. Atypia in the squamous metaplasia is frequently present as well and may be so striking as to suggest invasive carcinoma (Figure 5.13). The location of the squamous metaplasia in and around bronchioles along with the associated DAD should indicate the correct diagnosis.

Occasionally, in severely hypoxemic patients, small infarcts are seen, usually in peripheral, subpleural parenchyma. They are likely caused by severe hypoxemia, and the arterial thrombi may also be a contributing factor.

FIGURE 5.6 Organizing DAD. (A) At low magnification, relatively uniform cellular thickening of alveolar septa is noted, and adjacent airspaces appear dilated. (B) At higher magnification, the interstitial thickening is due mainly to fibroblasts within lightly staining stroma. Scattered tiny, partially collapsed airspaces lined by hyperplastic pneumocytes are also present (arrows), and there is a hyaline membrane remnant (arrow head). These findings indicate injury occurring at least 2 weeks earlier. DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

FIGURE 5.7 Organizing DAD. (A) At low magnification, striking interstitial thickening is appreciated with small residual airspaces in some areas and dilated airspaces in others. The thickened interstitium appears cellular. (B) Higher magnification of the circled area in (A) shows prominent entrapped and collapsed alveoli lined by hyperplastic pneumocytes (hobnail-shaped cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, center top) that are present in the thickened interstitium in addition to fibroblasts. Mild chronic inflammation accompanies the changes as well. The findings indicate injury occurring at least 2 weeks previously. DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

FIGURE 5.8 Cytokeratin immunostaining in organizing DAD. (A) At low magnification, numerous entrapped alveolar pneumocytes are highlighted within the thickened interstitium. (B) A higher magnification better illustrates the numerous small and often collapsed alveolar remnants (dark brown) within the background fibroblast proliferation. The light brown stained areas represent hyaline membrane remnants that have also been incorporated into the interstitium. DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

FIGURE 5.9 Hyaline membrane remnants in organizing DAD. (A) Hyaline membrane remnants are seen along alveolar septa thickened by fibroblasts in this area of otherwise typical organizing DAD. A few mononuclear inflammatory cells are also present within airspaces. (B) Nearby, typical organizing DAD is present with prominent, entrapped, partially collapsed alveoli lined by hyperplastic pneumocytes in the thickened interstitium along with fibroblasts. Stars indicate adjacent alveolar spaces. DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

FIGURE 5.10 Organizing DAD. (A) In this case, the fibrosis is so severe that the alveolated parenchyma appears almost solid. (B) A higher magnification shows the marked interstitial fibroblast proliferation with resultant reduction of airspaces to slit-like spaces. This severe fibrosis occurs after several weeks following injury. DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

FIGURE 5.11 Squamous metaplasia in DAD. (A) Low magnification showing prominent epithelial proliferation around a bronchiole. (B) At higher magnification, the squamous differentiation is better appreciated, and there is mild atypia. DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

FIGURE 5.12 Alveolar pneumocyte atypia in DAD. (A) In this example, some alveolar lining cells are enlarged and contain prominent nucleoli. (B) The alveolar pneumocytes in this example are more severely atypical with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli as well as varying size and loss of orientation (top). Inset from another area shows an atypical mitotic figure in addition to cytologic atypia. DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

FIGURE 5.13 Florid squamous metaplasia with atypia in organizing DAD. (A) Low and (B) high magnification of a squamous proliferation that is so marked that it may suggest invasive squamous cell carcinoma. DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

FIGURE 5.14 Combined acute and organizing stages of DAD. (A) In this field, well-formed hyaline membranes are present along alveolar septa that are thickened by fibroblasts, whereas in other areas (B) alveolar septal fibroblast proliferation and alveolar pneumocyte hyperplasia are present without hyaline membranes. DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

It is not uncommon to find areas of acute DAD superimposed on organizing DAD. Although remnants of hyaline membranes may be present in ordinary organizing DAD, combined acute and organizing DAD cases contain areas of well-formed hyaline membranes in a background of organizing DAD (Figure 5.14). The changes are indicative of ongoing or recurrent injury, and they should be diagnosed as acute and organizing DAD. For estimating the time of onset of injury, the most advanced changes should be used.

Differential Diagnosis

Very few entities enter the differential diagnosis of the acute stage of DAD because hyaline membranes are quite specific. As infections in immunocompromised persons, especially viral and pneumocystis, can cause acute DAD, a careful search for organisms should be undertaken in this setting.

The main lesion in the differential diagnosis of organizing DAD is organizing pneumonia (OP; see Chapter 4, Figures 4.1 to 4.5), as both are characterized by prominent fibroblast proliferation. Their main distinguishing features are contrasted in Table 5.1. In most cases, the diagnosis is not difficult, as OP involves predominantly the airspaces in peribronchiolar parenchyma, whereas organizing DAD is predominantly interstitial, involving distal parenchyma unrelated to bronchioles. The diagnosis may be difficult, however, when the OP areas are more diffuse causing loss of the peribronchiolar location and blurring of the distinction between airspace and interstitial involvement. The most helpful feature for identifying DAD in difficult cases is finding other changes indicative of acute lung injury, such as hyaline membrane remnants, alveolar pneumocyte hyperplasia, squamous metaplasia in bronchiolar epithelium, and fibrin thrombi. Knowledge of the clinical situation is also helpful, as most patients with DAD receive mechanical ventilation in contrast to most patients with OP.

The situation is further complicated in that focal areas of OP are frequently found in a background of otherwise typical organizing DAD. Even if OP areas are present in the background of organizing DAD, they are of no significance in this situation, and they do not need to be diagnosed. The prognosis in such cases, unfortunately, is that of DAD (see subsequent section, “Clinical Features”), which is considerably worse than that of OP.

TABLE 5.1 Contrasting Features of Organizing DAD and OP

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree