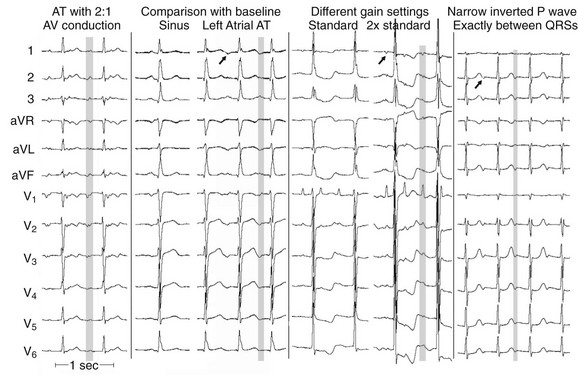

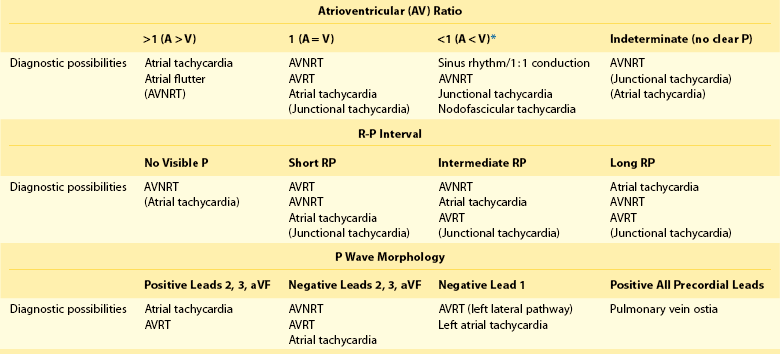

59 The major categories of NCTs include those that are primarily atrial in origin (atrial tachycardia, flutter, fibrillation); those that are based in the atrioventricular (AV) junction; and those that incorporate atrium and ventricle in a large circuit (accessory pathway medicated AV reentry). In this chapter, atrial fibrillation will not be considered further, but flutter and atrial tachycardia (AT) deserve consideration. Classic electrocardiographic atrial flutter is now understood to be a continuous wave front propagating either clockwise or counterclockwise around the tricuspid annulus. Other atrial arrhythmias are termed flutter on electrocardiogram (ECG) but are mechanistically distinct; these can be focal in origin or reentrant (usually large circuits bounded by natural barriers such as valves or scar tissue). ATs can be focal (true focus or microreentry that appears focal in its propagation pattern) or macroreentrant, incorporating significant amounts of atrial tissue in the circuit. The latter are noteworthy in that the P wave makes up a relatively large portion of the tachycardia cycle, as opposed to focal ATs (and all other types of SVT, during which atrial activation begins at a discrete point as though it were a focus).1 A major limitation of discerning P-wave morphology is the need to determine what is a P wave and what are ST segment, T wave, and QRS complex. Helpful aids include finding periods of NCT with 2 : 1 AV conduction; comparing the complex in question with a sinus rhythm P-QRS-T cycle; and increasing ECG gain (Figure 59-1). Among NCTs, the differential diagnosis is based on the A : V ratio; among those with 1 : 1 AV ratio, the timing of the P wave relative to a QRS complex; and P-wave morphology (Table 59-1). Although individual variability is noted, some patterns are relatively constant. Table 59-1 Narrow Complex Tachycardia Diagnostic Features AVNRT, Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; AVRT, atrioventricular reentry tachycardia. *All four items in this group are rare. Diagnostic possibilities are listed in order of frequency. Terms in parentheses denote rare situations. 1. NCTs with A : V ratio >1 include AT and flutter, as well as rare cases of AVNRT with 2 : 1 block, usually in the His bundle (Figure 59-1, far right). 2. NCTs with A : V ratio = 1 comprise a large and heterogeneous group, among which are AVNRT, AVRT, AT, and the uncommon automatic junctional tachycardia. ATs at times may have a 1 : 1 AV ratio, but the timing relationship between QRS complex and the subsequent P wave is not fixed. 3. NCTs with A : V ratio <1 are rare and include sinus rhythm with simultaneous conduction over fast and slow AV nodal pathways, nodofascicular pathway–based reentry, and either AVNRT or junctional tachycardia with retrograde block. B R-P interval in cases with 1 : 1 A : V ratio 1. Absence of a visible P wave (subsumed in the QRS complex) is common in AVNRT (anterograde slow, retrograde fast pathways) but can occur in AT with a long AV conduction time. 2. NCTs with a short R-P interval (P wave in the first one-third of the R-R interval) include AVRT, AVNRT (especially in patients >50 years old), and AT, with junctional tachycardia a rare diagnosis. 3. Intermediate R-P interval NCTs (P wave in middle one-third of the R-R interval) are of the same types as short R-P NCTs, but AVNRT (“slow-slow”) and AT are more common than AVRT. 4. Long R-P NCTs are an interesting group with the same diagnostic possibilities as are seen in the other R-P subsets, but ATs predominate; AVNRT is of the less common “fast-slow” variety, and accessory pathways are of the very uncommon slowly conducting type. 1. Atrial activation in NCTs with positive P waves in the inferior leads begins near the top of the atria, including the upper crista terminalis, superior vena cava, and appendage in the right atrium, and the pulmonary veins and appendage in the left atrium, as well as cephalad portions of the tricuspid and mitral annuli. Evaluation of precordial leads (anteroposterior) and lead 1 (left-right) further refines the site of origin in the other two planes. As such, ATs account for many of these, but AVRT with pathway atrial insertions on the tops of mitral or tricuspid annuli are also part of this group. 2. Negative P waves in the inferior leads denote onset of atrial activation in the lower portion of the atria (low crista terminalis, coronary sinus os, low septum, and tricuspid annulus in the right atrium, and low septum or mitral annulus in the left atrium). All varieties of AVNRT as well as AVRT using posterior AV pathways fall into this group, as do some ATs. 3. An inverted P wave in lead 1 is a reliable indicator of left-to-right atrial activation, either from AT arising in the left atrium or pulmonary veins, or from AVRT using a left lateral pathway. 4. When all precordial leads show positive P waves, a left atrial or pulmonary venous source should be suspected.

Differential Diagnosis of Narrow and Wide Complex Tachycardias

Narrow QRS Tachycardias

Diagnostic Possibilities

Electrocardiographic Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis of Narrow and Wide Complex Tachycardias