Diaphragmatic Injuries

Julian Guitron

John Howington

Joseph LoCicero III

In 1541, Sennertus41 first described diaphragmatic injury. In 1578, Ambrose Paré17 described two cases that resulted in death. In 1886 the first surgical repair in the trauma setting was reported by Riolfi.20 Since the diaphragm does not heal spontaneously, even small tears must be repaired surgically. If the diaphragmatic wound is missed, one or more of the abdominal viscera will eventually herniate into the thoracic cavity, resulting in significant morbidity and potential mortality. Traditionally, injuries to the diaphragm occur in 5% of patients with thoracoabdominal trauma patients; missed tears are reported to affect as many as 50% of the cases.

Virtually all the patients who suffer a diaphragmatic rupture sustain multiple additional injuries that obscure any specific signs or symptoms. Even small injuries such as those caused by stab wounds may progress to dangerous visceral herniation.

Patients with diaphragmatic wounds fall into two broad categories: those recognized in the acute setting after trauma, and those missed initially and recognized after the original hospitalization, grouped under late setting after trauma.

Acute Setting After Trauma

In the acute setting, the mechanism of injury makes a big difference in incidence, laterality, and diagnosis. These are discussed separately below.

Blunt Diaphragmatic Trauma

Hanna and associates18 state that the typical mechanisms that result in diaphragmatic rupture are motor vehicle accidents (80%), falls from great height (10%), and crushing injuries (10%). In patients experiencing severe blunt trauma who survived long enough to be admitted to the hospital, the incidence of diaphragmatic rupture was at least 3%.4,43 Shah and colleagues42 found the following distribution of rupture: left diaphragm, 68.5%; right diaphragm, 24.2%; bilateral, 1.5%; pericardial, 0.9%; and unclassified, 4.9%. Since the right hemidiaphragm, which cushions blunt force trauma, is in proximity to the liver, the liver ruptures much less frequently than the diaphragm.45 Right-sided injuries are usually posterolateral to the central tendon, but the pericardial or central portion of the diaphragm may also tear.

Anatomic Considerations

Herniation through the acute rupture is about 66% more common after blunt injury than after penetrating injury. The most commonly herniated organs on the left side are the stomach (50%), spleen (26%), and small bowel (13%). Liver, colon, and omentum also herniate through the diaphragm, but the incidence of these events is difficult to quantify.

When herniation occurs on the right, the liver is always at risk, while the second most common organ to be affected is the colon.7 Rupture of the right hemidiaphragm is frequently associated with vascular injuries, particularly of the vena cava and hepatic veins.

Clinical Presentation

Only a minority of patients present with the signs and symptoms of diaphragmatic rupture, which typically include respiratory distress, cardiac abnormalities, deviated trachea, and bowel sounds in the chest. Although these may be present, most patients present with signs and symptoms related to other organ system injuries resulting from high-energy trauma. Because of the associated injuries and the common finding of hypovolemic shock, these symptoms are obscured.

Diagnosis

The widely adopted FAST (Focused Assessment by Sonography in Trauma) examination in the initial assessment of the trauma patient has prompted several reports that recommend its use to assess diaphragmatic injury.2,5 Immobile diaphragm or abnormal diaphragmatic motion is diagnostic of rupture. In patients requiring emergency exploration for any other life-threatening injuries, the diagnosis should be made at surgery. Therefore both leaves of the diaphragm must be thoroughly inspected as part of any exploratory laparotomy.

Radiographic Examinations

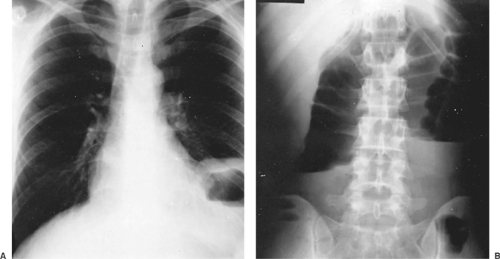

Routine radiography of the chest is the best initial study. Gelman and colleagues14 found that the chest radiograph was diagnostic in 46% of the cases and was considered suspicious enough to warrant further workup in 18% of the patients who suffered a left-sided rupture. For right-sided tears, they found only 17% of the initial radiographic exams suspicious enough to warrant further workup. Common findings depicted in Figure 77-1

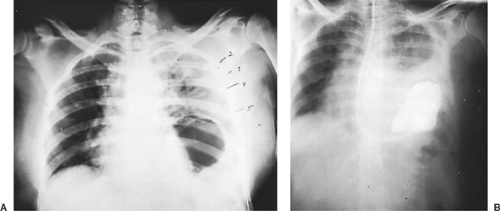

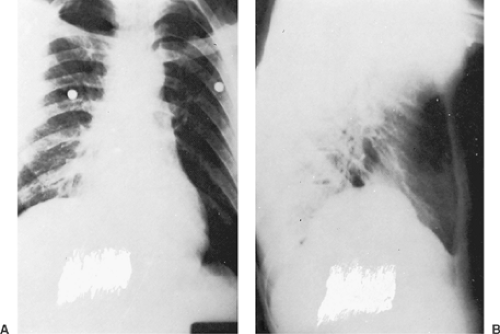

include an elevated, obscured, or irregular diaphragmatic dome on the affected side, and a blunted costophrenic angle. One or more air–fluid levels and radiolucency may be seen in the lower lung field (left side), as well as shifting of the mediastinum away from the side of the hernia. Figure 77-2 demonstrates the diagnostic finding of a nasogastric tube turned upward into the chest. Occasionally a rounded shadow protruding above the right hemidiaphragm appears on the lateral film, which is highly diagnostic for right-sided rupture (Fig. 77-3). Nondiagnostic findings such as pneumothorax and hemithorax are frequently present.

include an elevated, obscured, or irregular diaphragmatic dome on the affected side, and a blunted costophrenic angle. One or more air–fluid levels and radiolucency may be seen in the lower lung field (left side), as well as shifting of the mediastinum away from the side of the hernia. Figure 77-2 demonstrates the diagnostic finding of a nasogastric tube turned upward into the chest. Occasionally a rounded shadow protruding above the right hemidiaphragm appears on the lateral film, which is highly diagnostic for right-sided rupture (Fig. 77-3). Nondiagnostic findings such as pneumothorax and hemithorax are frequently present.

In patients who do not require emergency operation, the diagnosis may be confirmed with barium contrast images of either the upper or lower gastrointestinal tract. Computed tomography (CT) likewise can demonstrate the herniation.22,46 Killeen and colleagues26 found that the sensitivity was 78% and specificity 100% for left-sided injuries; for right-sided injuries, the sensitivity was 50% and the specificity 100%.

Options that further examine the possibility of a diaphragmatic tear on the right side include fluoroscopic and radionuclide liver scan imaging, as well as ultrasound (US) and CT. Prior reports have shown that US has excellent sensitivity in detecting diaphragmatic pathology, albeit in nontrauma situations.15 The use of diagnostic pneumoperitoneum and bronchography is of historic interest only.

Role of Thoracoscopy

Thoracoscopy as a tool for the evaluation of chest injuries was first reported by Jackson and Ferreira in 1976.24 They used a rigid-tube scope in 11 patients, finding 2 diaphragmatic disruptions. In 1981, Jones and colleagues25 reported their series of 36 patients, sparing 44% of their patients an open exploration. It was not until 1993 that the use of modern video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) was reported by Ochsner and his group.38 Since then, several authors have confirmed the validity of this diagnostic and potentially therapeutic procedure,28,33,39,44 including Mouroux and his group,35 who presented their experience over 12 years in 12 patients who underwent VATS plication of the diaphragm for symptomatic eventration, with excellent results.

Treatment

Diaphragmatic ruptures should be repaired surgically as soon as possible, given the risk of developing respiratory and even circulatory compromise—in addition to bowel obstruction once the herniated portion of gastrointestinal tract incarcerates or strangulates. The surgical options to treat diaphragmatic injuries include laparoscopy, thoracoscopy, laparotomy, and thoracotomy.

Although either hemidiaphragm may be best exposed through the chest, the type of approach should be customized for each patient. A source of massive bleeding is usually a lacerated abdominal organ; therefore an abdominal approach is more desirable.4 During the acute postinjury period, the diaphragmatic injury should be repaired through the incision required for the repair of other organ injuries. Symbas and associates45 were able to treat all diaphragmatic injuries through a laparotomy incision.

Left hemidiaphragmatic ruptures are most often repaired transabdominally because of frequent associated injuries. When an abdominal exploration is not indicated, a left thoracotomy is favored. Right-sided tears are traditionally repaired through a right thoracotomy.11 However, even on that side, the optimal approach is determined on a case-by-case basis; for instance, a midline incision can be extended to a median sternotomy to place an atriocaval shunt to control massive retrohepatic bleeding.10 Once all associated visceral injuries are repaired, the diaphragmatic tear is closed with interrupted figure-of-eight large-caliber nonabsorbable sutures. Prosthetic material is rarely needed with acute blunt trauma injuries.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree