INTRODUCTION

Learning Objectives

The student will be able to identify clinical indications and contraindications for flexible bronchoscopy for diagnostic evaluation of respiratory system diseases.

The student will be able to describe the stepwise performance of a diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy, the equipment utilized, and possible complications.

The student will be able to enumerate the types of diagnostic samples obtained by flexible bronchoscopy and their utility in establishing an etiologic diagnosis.

Bronchoscopy adds light and color to the study of diseases of the respiratory system. As one of the most important diagnostic procedures in pulmonary medicine, it enables the physician to visually inspect the tracheobronchial tree and to obtain samples from the lungs, including distal air spaces, in a non-invasive fashion. Clinical bronchoscopic procedures date back to Gustav Killian, who in 1897 performed the first inspection and therapeutic intervention within the human tracheobronchial tree. Reports indicate that he used a rigid bronchoscope to successfully remove a foreign body lodged in the patient’s right mainstem bronchus. During the early twentieth century, a rigid bronchoscope remained the only tool available to thoracic physicians to diagnose and treat diseases of the respiratory system. Such rigid bronchoscopes consisted of a hollow metal tube plus a light source that allowed for passage of suction catheters and various tools to extract aspirated foreign bodies. The rigid bronchoscope did not allow access to smaller lobar airways or to any airway segment that could not be linearly aligned with the oropharynx. In 1967, Ikeda of Japan developed the flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope, enabling procedures to be performed with greater ease and comfort for awake patients using minimal anesthesia, and giving access to segmental and even subsegmental airways.

CONTEMPORARY BRONCHOSCOPY EQUIPMENT

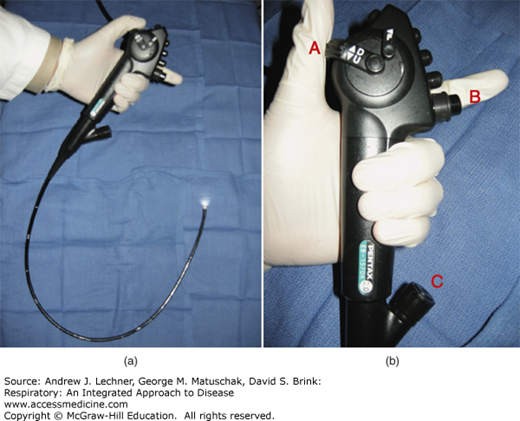

The modern flexible adult bronchoscope has a diameter of 5-6 mm and is 50-60 cm in length (Fig. 18.1). Most flexible bronchoscopes have a fiberoptic light source as well as a lens for viewing, and a hollow channel for suction that also permits the passage of instruments to and beyond the distal tip of the bronchoscope. Such bronchoscopes are maneuvered manually through the patient’s airways by variably deflecting its distal end, using a lever mounted on the proximal portion of the instrument that is held by the physician. Images are generally displayed on a video screen in the bronchoscopy suite or at the bedside of critically ill patients. In addition to providing a means to aspirate tracheobronchial secretions, blood, or other airway debris via suction, the hollow working channel allows for the passage of a wide variety of specially designed tools into the airways. These include small sampling brushes, miniature forceps for obtaining tissue samples and needles for obtaining aspirates. The working channel can also be used to deliver medications such as topical anesthetic and to deliver saline to lavage the airways (see below).

FIGURE 18.1

(a) Adult flexible fiberoptic video bronchoscope, with illumination evident at distal end. (b) Close-up view of bronchoscope handle showing directional lever used to flex or extend its distal tip (A), suction control button (B), and proximal port (C) for accessing the internal channel that extends to the distal tip.

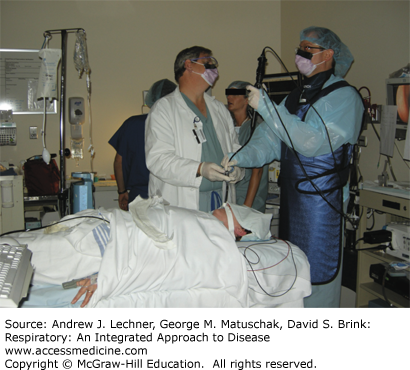

The modern bronchoscopy suite (Fig. 18.2) usually is a room specifically equipped for, and dedicated to, these procedures. In some clinical settings, bronchoscopies may be performed in a common area used for multiple types of endoscopic procedures. Bronchoscopies are also routinely performed in operating rooms and intensive care units (ICUs). The bronchoscopy suite typically utilizes a bed or table that can accept a portable fluoroscopy “C-arm” unit for positioning over the chest region of interest. Radiological imaging using fluoroscopy increases patient safety when obtaining samples from the lung periphery through airways that are too small to permit direct visualization. Always present in the bronchoscopy suite is all equipment needed to automatically monitor a patient’s vital signs including a continuous reading of Sao2, and to provide supplemental O2, suction, and emergency resuscitation.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS FOR BRONCHOSCOPY

The possible indications for flexible bronchoscopy are numerous and will vary with the unique circumstances of each individual patient. In general, indications can be divided into those involving known or suspected abnormalities of the large airways, those involving the lung parenchyma, and abnormalities of extrapulmonary or mediastinal structures (Table 18.1). Indications where inspection and possible sampling of the large airways are the primary objectives include evaluation for suspected tracheal stenosis or excessive tracheal collapse during the respiratory cycles secondary to abnormal inflammatory softening of the tracheal walls known as tracheomalacia (Chap. 37). Likewise, bronchoscopy allows inspections for tracheobronchial obstruction, endobronchial tumors in patients with a known or suspected malignancy (Chap. 31), persistent atelectasis on thoracic imaging studies (Chap. 15), and investigation of hemoptysis. In other conditions such as penetrating or nonpenetrating thoracic trauma or inhalational injury, bronchoscopy is useful to directly assess acute airway damage and altered anatomical integrity. Indications for diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy where the primary objective is to sample the lung parenchyma include evaluating unexplained, recurrent or severe pneumonias, investigating diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), and sampling selected pulmonary nodules and mass lesions. Flexible bronchoscopy has a more limited role in diagnosing diffuse interstitial pulmonary processes (Chap. 24), although excluding infection and malignancy remain important. Indications where sampling of extrapulmonary or mediastinal structures is the goal include evaluating mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy, mediastinal masses and, increasingly, nodal involvement in patients with known or suspected lung cancer (Chaps. 31, 32, 33).

| Evaluation of Large Airway Abnormalities | Evaluation of Parenchymal Abnormalities |

|---|---|

| Tracheal stenosis | Pneumonia |

| Tracheomalacia | Pneumonitis |

| Upper airway obstruction | Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) |

| Hemoptysis | Pulmonary nodules and masses |

| Chronic cough | Diffuse lung disease |

| Endobronchial tumors | Sarcoidosis |

| Tracheobronchitis | Organizing pneumonia |

| Tracheobronchial trauma | Lung transplant rejection |

| Inhalational injury | |

| Evaluation of Extrapulmonary or Mediastinal Abnormalities | |

| Hilar and/or mediastinal lymphadenopathy | |

| Mediastinal masses | |

There are few absolute contraindications to diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy, and as for the indications, most contraindications vary with the unique circumstances of individual patients (Table 18.2). Impending hypoxic or hypercarbic respiratory failure without a secured airway (ie, an indwelling endotracheal tube to permit assisted ventilation and oxygenation) is a common contraindication. Likewise, nonsecured airways in patients with severe OSA, mixed sleep apnea, or OHS (Chap. 25) are contraindications, since sedating patients with these conditions for the procedure may worsen their reduced ventilatory drive and upper airway obstruction, culminating in progressively reduced V̇A, hypercapnea, and hypoxemia.

| Severe hypoxemia or hypercarbia with impending respiratory failure |

| Severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome without a secure airway |

| High grade tracheal obstruction |

| High inspired oxygen requirements |

| High airway pressures during mechanical ventilation |

| Untreated pneumothorax |

| Hemodynamic instability including shock |

| Unstable angina or recent myocardial infarction |

| Coagulopathy or platelet disorders |

| Recent oral intake |

| Inability to obtain informed consent |

| Lack of equipment or adequately trained personnel |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree