Diagnostic Evaluation of Anterior Mediastinal Masses and Clinical and Surgical Approach to Thymic Tumors via Sternotomy

Usman Ahmad

Frank C. Detterbeck

INTRODUCTION

Mediastinal tumors are relatively rare and can be of various origins. Their appearance is often variable, and there is overlap among different tumors. Therefore, it takes many years before one has seen enough of most types to be able to recognize patterns and develop an efficient clinical approach. This chapter presents a practical and logical approach for the workup of anterior mediastinal masses with a focus on thymic tumors, which are the most common and are the primary focus for thoracic surgeons.

The incidence of mediastinal tumors is difficult to define. This is due in part to the inclusion of benign cysts and lesions in some series and not in others. Probably most important, it is due to the inclusion of varying numbers of patients with lymphomas. Although about 50% of Hodgkin disease (HD) and 20% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) involve the mediastinum, only about 3% of HD and 6% of NHL involve the mediastinum exclusively. While inclusion of the latter groups as mediastinal tumors seems legitimate given the diagnostic issues they present, inclusion of the former group seems inappropriate if there are enlarged lymph nodes elsewhere, such as in the neck or axilla, which are more easily accessible for biopsy.

CLASSIFICATION OF THE MEDIASTINUM

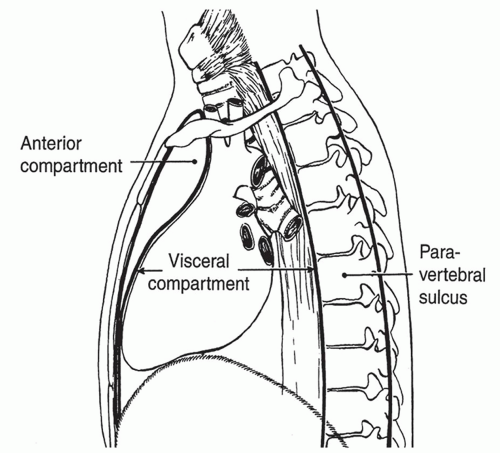

Several classification schemes for mediastinal compartments have been used. The scheme proposed by Shields is recommended and is currently used most frequently. It is based on anatomic landmarks and is easiest to translate to a computed tomography (CT) scan. This definition describes an anterior compartment, a visceral compartment, and a bilateral paravertebral compartment (Fig. 13.1). The anterior compartment extends between the posterior aspect of the sternum and the anterior surface of the pericardium and the great vessels. The visceral compartment includes the heart, great vessels, trachea, and esophagus, and is bounded posteriorly by the anterior spinal ligament (anterior surface of the vertebral bodies). The paravertebral compartment extends from this boundary to the posterior ribcage.

GENERAL APPROACH TO PATIENTS WITH ANTERIOR MEDIASTINAL TUMORS

Most of the literature regarding mediastinal tumors has been in the form of retrospective series of patients with a specific known diagnosis, and reported on characteristics of the patients. This is contrary to the clinician’s needs, who already knows about the clinical characteristics of an individual patient in question and is trying to ascertain the diagnosis. This chapter therefore starts with clinical features that are clearly defined (age, gender, location of the lesion), and some features that may be well defined (duration of symptoms, associated conditions or features, particular radiographic characteristics). Additional features may be clinically occult, but can be brought out by appropriate testing (laboratory results).

The approach begins with a history and physical exam. The degree and duration of symptoms and the presence of associated diseases can provide important clues to the diagnosis. This is supplemented with a CT scan of the chest. For mediastinal masses the CT scan should always be done with intravenous contrast in order to better define the relationship of the mass to the normal (vascular) mediastinal structures. The chest radiograph (CXR) and CT allow the tumor to be assigned to one of the mediastinal compartments. Although many tumors may overlap somewhat and not be completely restricted to a single compartment, in general the epicenter of the lesion or the bulk of the mass clearly falls within one of the mediastinal areas.

The anterior mediastinum is the most common site of mediastinal tumors, and generally presents the greatest clinical challenges in making a presumptive diagnosis. Overall, data from large series show the approximate relative proportion of tumors that occur in the anterior mediastinum to be thymoma 35%, benign thymic lesions 5%, lymphoma 25% (HD 13%, NHL 12%), benign teratoma 10%, malignant germ cell 10% (seminoma 4%, nonseminomatous germ cell tumor [NSGCT] 7%), and thyroid and other endocrine tumors 15%.

Assessing the clinical characteristics and presentation and defining which mediastinal compartment a tumor is in is an important step in the strategy of how to approach these patients. Despite the variety of tumors, a reliable clinical diagnosis often can be made using the combination of demographic factors, symptoms, and radiologic findings. In many cases, a presumptive clinical diagnosis can be made with sufficient confidence to justify proceeding with a treatment plan without further confirmation.

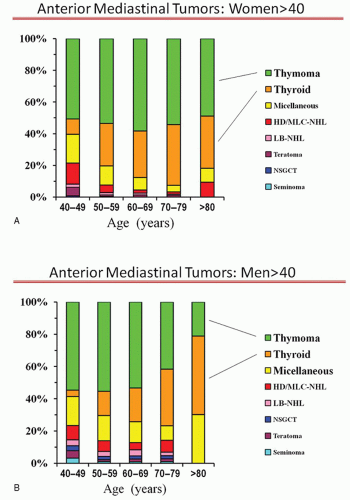

Patients over Age 40

The proportion of anterior mediastinal tumor types by decades of age for men and women over age 40 is shown in Figure 13.2A and 13.2B. Small differences by age and gender exist, but overall thymoma is the most likely tumor type. With increasing age, substernal thyroid goiters also account for a substantial proportion. Thyroid masses are generally easily and reliably recognized by a characteristic radiographic appearance (high density), continuity with the thyroid gland, and extension posterior to the great

vessels. In rare instances, an iodine 133 scintigraphy scan can be useful, although it must be remembered that an iodine scan is likely to have decreased sensitivity when performed within approximately 4 weeks of a CT scan involving iodinated contrast.

vessels. In rare instances, an iodine 133 scintigraphy scan can be useful, although it must be remembered that an iodine scan is likely to have decreased sensitivity when performed within approximately 4 weeks of a CT scan involving iodinated contrast.

Many patients (30% to 50%) with a thymoma will have an associated parathymic condition (e.g., myasthenia gravis [MG], hypogammaglobulinemia, pure red cell dyscrasia), which is virtually pathognomonic that an anterior mediastinal mass is a thymoma. In general, tissue confirmation of a thymoma or substernal goiter is not needed prior to resection.

The small remaining subset of patients (especially men and those aged 40 to 49) includes a variety of relatively rare tumors that require histologic confirmation for diagnosis. Preferably, the initial approach is a needle biopsy, but because of the variety and rarity of these tumors this may or may not be sufficient to reliably establish the diagnosis.

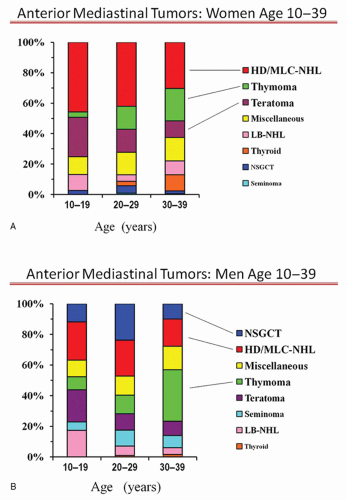

Women Aged 10 to 39

In women aged 10 to 39, the most prevalent tumor is HD or mediastinal large cell NHL (MLC-NHL) lymphoma (Fig. 13.3). Many have constitutional symptoms suggestive of lymphoma. In addition, although the epicenter of the mass is in the anterior mediastinum, there is often a fairly characteristic enlargement of multiple lymph nodes in the middle mediastinum and neck. Therefore, a clinical diagnosis of HD or MLC-NHL can be made quite reliably in a large proportion of women aged 10 to 39. However, this must be confirmed by a tissue biopsy. Although one may attempt a needle biopsy first, in most institutions this will be insufficient for full lymphoma characterization and a surgical biopsy will be needed (see later section on biopsy procedures).

A substantial portion of the remaining patients have a thymoma, especially those over age 20. Once again, due to the frequent occurrence of parathymic conditions that are essentially pathognomonic for thymoma, many of these patients can be very reliably identified on clinical and radiographic grounds.

The other tumor seen relatively infrequently compared to thymoma or lymphoma is a benign teratoma that can be easily identified based on radiographic and clinical features. Most are asymptomatic and when present, symptoms are typically long-standing (29% chest pain, 25% cough, 22% dyspnea, 9% pleural effusion, 1% superior vena cava [SVC] syndrome in 305 patients). The key radiographic feature is a focus of fat density, which is present in about 50%. These tumors are usually rounded with sharp margins, appear well encapsulated and cystic, and contain material of variable density, especially fat, soft tissue, and cartilage. Although 25% have calcification, less than 10% have areas resembling a bone or a tooth. Only 5% of benign teratomas are not in the anterior mediastinum (usually posterior).

Among the remaining patients, a small percentage has substernal thyroid goiter (easily recognized on a CT). In the 20 to 29 age group, about 5% of tumors in women are primary mediastinal germ cell tumors and in this group checking for elevation of alpha fetoprotein (AFP) and β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG) can be worthwhile (especially if the presentation is atypical for the more common lesions). Especially in the 10 to 19 age group, lymphoblastic NHL must be considered. These typically exhibit fulminant growth, rapid onset of symptoms, present with a large inhomogeneous mediastinal mass and often a pleural effusion. Cytologic findings are quite characteristic and sufficient to establish the diagnosis.

Men Aged 10 to 39

For men aged 10 to 39 there is no dominant tumor type (Fig. 13.3B); however, strong clues can usually be obtained from a clinical history. The rapidity of the onset of symptoms is usually the best marker. Features that are truly pathognomonic, however, are limited to a markedly elevated serum AFP or β-HCG levels, which are quite consistently found only in NSGCT and MG and establish an anterior mediastinal mass as a thymoma.

A rapid onset of symptoms (over days to several weeks) strongly suggests either NSGCT or lymphoblastic non-Hodgkin lymphoma (LB-NHL). Radiographically a bulky, inhomogeneous mass is usually seen in both, sometimes with areas of necrosis or hemorrhage. LB-NHL is more common in ages 10 to 20, and is often accompanied by a pleural effusion, “B” symptoms (fever, night sweats, weight loss), and an elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level. With NSGCT, however, pulmonary metastases are often seen but pleural effusions are uncommon.

The diagnosis of NSGCT is made easily and reliably by demonstrating markedly elevated serum AFP or β-HCG levels. This is present in 90% of NSGCT. A needle biopsy to confirm the diagnosis is not needed in experienced centers when the presentation is typical, as further subtyping of the tumor does not alter the treatment approach. The diagnosis of lymphoblastic NHL is usually easily made from a fine-needle aspiration of the primary mass or a pleural effusion due

to the presence of characteristic cytologic features. In addition, approximately 50% of patients have bone marrow involvement.

to the presence of characteristic cytologic features. In addition, approximately 50% of patients have bone marrow involvement.

An intermediate onset of symptoms (over many weeks to months) suggests a seminoma, HL or MLC-NHL. Radiographically, these two lymphoma types usually involve multiple enlarged lymph nodes or a multilobulated mass. Frequently nodal enlargement is also seen in cervical, hilar, or upper abdominal nodes in HD, whereas the vast majority of MLC-NHL involves only the mediastinum (sometimes with pleural or pericardial effusion). In both lymphoma types, B symptoms are often present. Seminomas, on the other hand, are usually homogeneous or slightly inhomogeneous with smooth pushing margins and only rarely are accompanied by a pleural effusion but often have associated pulmonary metastases.

About 10% of seminoma patients have a low grade elevation of serum β-HCG, whereas AFP is almost always normal. An elevated LDH level is common, but this is found in lymphoma as well. A core needle biopsy usually establishes the diagnosis of seminoma and is sometimes sufficient to establish the diagnosis of lymphoma, but usually more tissue is needed (i.e., a surgical biopsy) in order to complete the subtyping that is important in selecting the appropriate therapy. Both HD and MLC-NHL often have prominent sclerosis, so that a needle biopsy typically yields only a small amount of actual tumor tissue.

In general, when symptoms are present, teratomas should be resected, although they are benign. So-called malignant degeneration of a benign teratoma has only been reported in secondary benign teratomas (residual after chemotherapy for a malignant germ call tumor), and marked growth resulting in mediastinal compression has also only been reported in this context. Therefore, an asymptomatic benign primary teratoma may be left alone. A discrete mediastinal mass suggestive of thymoma should be resected, especially in young patients. Thymic hyperplasia does not necessarily need to be resected but in the presence of MG thymectomy often is the treatment of choice. Making the distinction between a discrete thymic mass and thymic hyperplasia is often difficult. No biopsy is needed prior to resection of these lesions.

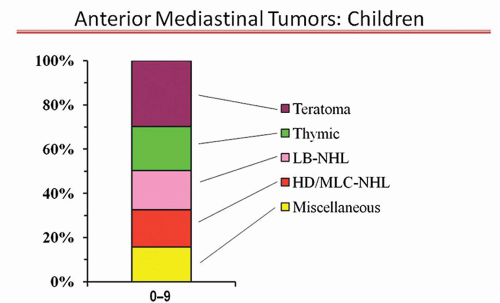

Children Aged 0 to 9

The proportion of anterior mediastinal tumor types in children aged 0 to 9 are shown in Figure 13.4. There is no dominant tumor type. A rapid onset of symptoms suggests a LB-NHL, an intermediate onset suggests HD/MLC-NHL, and more chronic symptoms a thymoma or teratoma. The same specific clinical symptoms, radiographic features, and laboratory tests as discussed in the previous section also apply to this age group. The selection of what confirmatory test to pursue is also the same.

THYMIC TUMORS

Clinical Presentation

Thymomas are relatively rare and usually indolent tumors that present with vague and subtle symptoms. Thymomas have been reported from ages 8 to 94 years. A broad peak is noted from 35 to 70 years. Patients with MG tend to present at a slightly younger age. While one-third of patients with thymoma present with MG, another one-third are asymptomatic. Approximately 40% of patients with thymoma present with local symptoms, while 30% have systemic symptoms. Cough, dyspnea, and chest pain are the most common symptoms. Dyspnea can result from local compression as well as from the neuromuscular effects of MG. Parathymic syndromes are common and aid in diagnosis (e.g., MG in 30%, pure red cell aplasia, and hypogammaglobulinemia in 2% to 5% each).

Imaging Characteristics

Radiographically, CT scan has high sensitivity (97%) in detecting these tumors. Intravenous contrast is helpful in determining vascular anatomy and relationship with the tumor. Thymomas typically appear as well-defined round or oval masses, generally anterior to the great vessels but can wrap around these structures. Curvilinear calcifications are seen in 10% to 20% of patients. Extension into mediastinal fat or pleura can be suggested on CT, however, is unreliable. The presence of smooth or lobulated contour, homogeneous enhancement, absence of areas of low attenuation, absence of pericardial or pleural effusion, and absence of calcification in the tumor favor the presence of a thymoma or a well-differentiated thymic carcinoma. A recent study showed that tumors that are greater than 7 cm in greatest diameter, infiltrate mediastinal fat, and have lobular appearance are more likely to be stage III/IV thymomas. Tumor size had the most robust association with advanced stage. In addition, pleural nodules were associated with stage IV disease.

Diagnosis

Using the combination of symptoms, associated conditions and radiologic findings, most thymomas can be reliably differentiated from other anterior mediastinal masses. A clinical diagnosis of thymoma is sufficient to plan operation for localized tumors. Tissue diagnosis is recommended for extensive tumors that require neoadjuvant chemotherapy or if anonoperative approach is planned. Sometimes it is difficult to differentiate thymoma from lymphoma due to lack of symptoms and equivocal radiologic findings; in this case open surgical biopsy is recommended.

Tissue diagnosis can be achieved through FNA or open biopsy (anterior parasternal mediastinotomy, thoracoscopy). The success rate is higher with open biopsy (90%), as compared to FNA (62%). Standards for performance and reporting of microscopic findings of needle biopsies of suspected thymomas have been established and should be followed. The suspicion of tumor seeding at biopsy site or needle tract is not substantiated by evidence or the experience at major centers where this has been commonly performed.

Histologic and Stage Classification

Despite their indolent behavior, and frequent lack of malignant cytologic features, all thymomas (regardless of initial stage or histologic type) have been noted to develop extrathymic invasion, local recurrence, and metastasis after resection, and therefore should not be labeled as “benign” tumors. The majority of thymic tumors have nonmalignant-appearing thymic epithelial cells mixed with variable proportions of lymphocytes. A small proportion of cases has cells with malignant features and is labeled as thymic carcinoma. These tumors account for less than 10% of cases in surgical series and about 15% overall and have more aggressive local and systemic behavior and worse prognosis. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies thymic tumors as type A, AB, B1, B2, B3, and thymic carcinoma. However, tumor heterogeneity is common, and application of the WHO classification has been found to be associated with significant interobserver variability.

Multiple staging schemes have been proposed; the Masaoka classification with Koga modification is endorsed as the current international standard by the International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group (ITMIG). The scheme (Table 13.1) is focused on local extension of the primary tumor with less emphasis on nodal involvement (this is the natural history of majority of thymomas, while thymic carcinomas can have nodal spread).

In general, approximately 40% of thymomas present as stage I lesions, 25% each at stages II and III, 10% at stage IVa, and 1% to 2% at stage IVb. Invasion into mediastinal tissue (stage II, III) is present in 50% of thymomas, with pleural invasion being most commonly followed by pulmonary and pericardial invasion. Approximately 30% of these cases have involvement of the innominate vein or SVC and 20% have phrenic nerve involvement. Direct extension is also seen into the aorta and pulmonary artery (11%) and chest wall (8%).