Diagnosing and Managing Internal Iliac Artery Aneurysms

RAFAEL D. MALGOR and GUSTAVO S. ODERICH

Presentation

A 72-year-old male patient with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, colonic diverticulosis, constipation, and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is referred for evaluation of left lower extremity edema, cyanosis, and left lower abdominal discomfort that have gradually worsened over the past 2 weeks. The patient denied history of traumatic injuries or prior venous thrombosis. When questioned about similar symptoms in the past, he recalled an episode of urinary retention that resolved after urinary catheterization. A month prior to presentation, the patient underwent a transurethral resection of prostate (TURP) and cystoscopy, which was negative for any masses. His last month digital rectal exam was unremarkable for any gross abnormalities except prostate enlargement compatible with BPH; his prostate-specific antigen was within normal limits. The patient also denied any previous episodes of diverticulitis. He had no fever, chills, weight loss, and changes in bowel habitus, blood per rectum, hematuria, or dysuria. His surgical history was notable for open appendectomy, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, left great saphenous vein stripping, open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, and right total knee replacement. The patient states that he only drinks alcohol on special occasions and that he had a 65-pack-year smoking history but has recently quit. He denied intravenous drug abuse. His father and mother had passed away of causes that were unknown to him.

At presentation, the patient is not in any acute distress. Positive findings of physical examination are a left lower quadrant machinery-type bruit radiating to the left groin but no abdominal tenderness to palpation. The abdomen was not distended, and no ecchymosis or mottling was noted. No abdominal pulsatile mass was felt, and lower extremity pulses were easily palpable throughout the lower extremities. Engorged veins were easily seen in the groin and proximal thigh area. There was a palpable thrill in the left groin. Significant edema in the entire left lower extremity along with modest cyanosis was clearly noted compared to his right lower extremity (Fig. 1). Laboratory test results, such as complete blood count, coagulation, and chemistry panel, were within normal limits.

FIGURE 1 72 year-old male with left lower extremity edema and audible left lower quadrant machinery-type bruit.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of left lower extremity edema is broad, but machinery-type bruit and left lower quadrant discomfort are strongly suggestive of an arteriovenous fistula (AVF). The most common causes of acquired AVFs are traumatic injuries, such as penetrating or blunt trauma, prior endovascular procedures, and abdominal, pelvic, or spine surgery. On rare occasions, patients with aortic or iliac artery aneurysms can present with contained rupture of the aneurysm into a large vein causing a spontaneous AVFs. The most common location is an aortic aneurysm associated with aortocaval fistula. Our patient denied any traumatic injuries or spine surgery. His only pelvic procedure was TURP for BPH.

A rare complication of TURP is the occurrence of an AVF associated with the procedure, but this is extremely rare. Lower extremity edema can be found in this particular scenario, but it is often seen in patients with sizeable, high-flow AVFs. Another symptom often associated with AVF secondary to TURP is hematuria. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) should be in the differential diagnosis of any patient with asymmetric lower extremity edema. Often, DVT is associated with lower extremity pain, which is not present in this scenario. Other classic predisposing factors for DVT, such as major surgery, multiple trauma, hip or knee surgery, prolonged immobility, or known malignancy, are not present. Most importantly, the presence of a left lower quadrant bruit favors the diagnosis of an AVF over DVT.

Workup

A duplex ultrasound of lower extremity veins was obtained that revealed no evidence of DVT but arterial waveforms consistent with AVF. A computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the abdomen and pelvis was performed. It is not infrequent that a CT with oral contrast is performed to rule out intra-abdominal inflammatory or infectious disease, such as diverticulitis or infectious colitis, in a patient who presents with abdominal discomfort of unknown cause. In this patient with a bruit suggestive of AVF, a CTA with lower extremity runoff is the most appropriate imaging study, providing detailed imaging for diagnosis and therapeutic planning. In addition, helical CTA provides small cuts (≤3 mm) and delineate the vascular anatomy in preparation for potential endovascular treatment. If a patient with suspected large-volume AVF involving the aorta or iliac arteries, or in those with symptomatic aneurysm disease, a CTA should be obtained.

Lower extremity venous duplex ultrasound in patients with lower extremity edema is an excellent screening study. Advantages include low cost, portability, safety to use, ease of repetition, and noninvasive features. In this patient, a DU was obtained, confirming the diagnosis of AVF and no evidence of DVT. However, the study is limited in its ability to provide enough anatomical information for definitive diagnosis and therapeutic planning. It can be limited in some patients because of bowel gas and body habitus. In this particular scenario, there was no contraindication for CTA that is a more complete and detailed study especially to rule out an AVF in the pelvis. Further, CT is not operator dependent, and it can be obtained in a very expeditious manner.

Workup (CTA of the Abdomen and Pelvis)

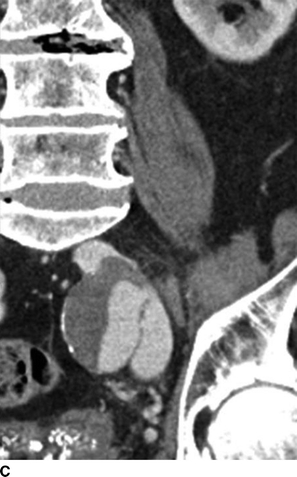

A CT of the abdomen showed an AVF between a 4-cm left internal iliac artery (IIA) aneurysm and the left internal iliac vein (Fig. 2). The right CIA and IIA were patent and nonaneurysmal. Colonic diverticulosis, but no inflamed diverticula, was also noted.

FIGURE 2 A: This CTA of the abdomen shows simultaneous contrast enhancement of both common iliac artery and vein. B and C: An arteriovenous fistula is suspected between a 4cm-IIAA and the iliac vein. The communication between the IIAA and the vein can be clearly identified.

Diagnosis and Treatment

The diagnosis is a symptomatic AVF between a left internal iliac artery aneurysm (IIAA) and left internal iliac vein. Nonetheless, the majority of IIAAs are first diagnosed incidentally by abdominal imaging (CT or ultrasound) performed for other reasons. Up to one third of patients with AAAs have an iliac artery aneurysm. On the other hand, 70% to 80% of patients with iliac artery aneurysms have AAAs. The estimated incidence of isolated iliac artery aneurysms, which most commonly involves the common iliac artery, is only about 2% of all intra-abdominal aneurysms. Of those isolated iliac artery aneurysms, approximately 20% are confined to the IIA. Overall, isolated IIAAs occur in approximately 0.3% to 0.5% of patients with intra-abdominal aneurysms. The majority of patients with IIAA are male with a mean age of 72 years, which is compatible with our case.

The natural history of IIAAs still remains unknown. The vast majority of patients remain asymptomatic. In contemporary reports, most patients with IIAAs are asymptomatic and treated in conjunction with concomitant aortic or common iliac artery aneurysms. Nonetheless, IIAAs can cause complications by rupture or local compression of adjacent organs. Patients with IIAAs can present with urinary symptoms, renal failure, lumbosacral, groin, hip or buttock pain, rectal bleeding, constipation, or DVT. Similar to our case, urinary symptoms are often obstructive in nature due to compression of the bladder by the aneurysm or caused by ureteric compression with subsequent hydronephrosis, pyelonephritis, and renal failure. Intermittent hematuria secondary to a ruptured IIAA into the bladder has been reported associated or not with scrotal ecchymosis. Left lower quadrant discomfort is usually secondary to compression or deviation of the sigmoid colon and rectum by the aneurysm causing worsening of constipation, tenesmus, and rectal pain. Due to its pelvic location, neurologic symptoms related to nerve compression, such as ipsilateral leg pain, paresis, sciatic neuralgia, and lumbosacral pain secondary to compression of the pelvic and lumbosacral nerve roots, have also been reported.

There are several potential treatment options for patients with IIAAs. The relationship between IIAA size and rupture has not been well established. Current recommendations for repair include presence of rupture, symptoms, or a size diameter of 3 to 4 cm in asymptomatic patients. In the patient herein described, treatment is recommended independent of the size of the aneurysm. Nonetheless, most patients with symptoms have large aneurysm, as exemplified by this case. Treatment selection should take into consideration the size, extent of disease in the contralateral IIA, involvement of other aortic segments, and patency of IIA branches. A critical question is the presence of bilateral IIA involvement or adequacy of the contralateral IIA. Preservation of pelvic flow is important to prevent ischemic complications. In patients with unilateral IIAAs, surgical ligation or more frequently IIAA catheter embolization can be performed with low rate of severe ischemic complications because of rich cross-pelvic collateral network. In these patients, embolization of distal branches is more frequently associated with ischemic symptoms as compared to exclusion of the main trunk of the IIA. One exception is patients with aortic disease affecting the thoracic or thoracoabdominal segments. In these patients, preservation of any IIA flow is critical to help prevent spinal cord injury; embolization of IIA should therefore be avoided whenever possible.

Bilateral involvement of the IIA can be challenging, particularly if the aneurysm involves the distal branches. Exclusion of both IIA can be performed but carries a higher risk of serious ischemic complications, such as ischemic colitis, buttock muscle, or pelvic ischemia. More frequently, patients may notice erectile dysfunction and/or buttock claudication. In these patients, preservation of at least one of the IIAs is recommended.

Endovascular interruption of the IIA can be performed using several techniques. Most often this is done with coil embolization, placement of endovascular plugs, stent graft coverage, or a combination of these. In this patient with AVF, it is critical to eliminate inflow into the fistulous communication. Because the right IIA was patent, exclusion of the left IIA was the least invasive and most straightforward alternative. This was done by placement of coils and Amplatzer plugs into the distal branches of the IIA along with coverage of the proximal IIA inflow by placement of a stent graft from the left CIA to the EIA.

Open repair remains an option but carries higher risk of complications in a patient with AVF and large collateral veins adjacent to the aneurysm. Other more advanced endovascular and hybrid techniques are available if preservation of IIA flow is indicated or warranted (see below).

Case Continued

All potential risks including, but not limited to major bleeding, buttock claudication, erectile dysfunction, colonic ischemia requiring colectomy and colostomy creation, myocardial infarction, stroke, and death and the benefits of excluding the left common and IIAAs were discussed at length with the patient. Three units of pack red blood cells were typed, and prophylactic antibiotics were ordered to be given within an hour prior to starting the procedure.

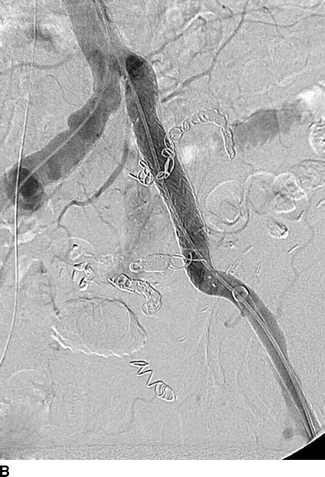

The patient was then taken to a hybrid operating room that is equipped with wall-mounted fluoroscopy unit. Ultrasound-guided puncture of the right common femoral arteries (CFAs) was performed. A 5-French Omni-flush catheter was positioned in the abdominal aorta. An aortogram with iliac angiography was obtained to delineate the anatomy and obtain measurements of proximal and distal landing zones in the common and external iliac artery anatomy. Using contralateral right femoral access, a 45-cm long, 6-French sheath was advanced up an over the aortic bifurcation into the left IIA. Selective catheterization of the IIA divisional branches was performed using a 100-cm, 5-French angled catheter. After selective angiography of each branch, coil embolization was performed using 0.035-inch coils to exclude the IIAAs outflow (Fig. 3A). Access from the left CFA was obtained and a 12-French sheath was advanced over an Amplatz wire into the left common iliac artery. After exclusion of the IIAA, a Gore Excluder stent graft limb was deployed from the left common to the external iliac artery covering the origin of the left IIA (Fig. 3B). Both femoral punctures were closed using a preclose technique with Perclose devices with no complications (Table 1).

FIGURE 3 Endovascular repair of left IIAA. A: Selective coil embolization of left IIAA via contra-lateral (up-and-over) approach. B: Iliac artery stenting with a 16x18x124 mm endograft limb across the IIA takeoff. Completion angiogram showing complete resolution of AVF.