and Paul L. Huang2

(1)

Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA

(2)

MGH Cardiology Metabolic Syndrome Program, Cardiology Division, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Abstract

Diabetes mellitus (DM) significantly increases risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the most frequent cause of death in patients with DM. Coronary disease in diabetic patients is often more complex, more widespread, and more diffuse, making revascularization options complicated. Patients with DM also suffer from an array of microvascular and macrovascular complications. However, the increased cardiovascular risk seen in these patients can be modified by lifestyle interventions, as evidenced by several large clinical trials. The cardiologist needs to be familiar with medical therapy for diabetes, as well as how DM affects management of established cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risks.

Abbreviations

3VD

3 vessel disease

ACS

Acute coronary syndrome

ADA

American Diabetes Association

AHA

American Heart Association

ATPIII

Adult Treatment Panel III

BMI

Body mass index

BS

Blood sugar

CAD

Coronary artery disease

CABG

Coronary artery bypass graft

CHF

Congestive heart failure

Cr

Creatinine

CVD

Cardiovascular disease

DES

Drug eluting stent

DM

Diabetes mellitus

DM1

Diabetes mellitus Type 1

DM2

Diabetes mellitus Type 2

DPP4

Dipeptidyl protease-4

GI

Gastrointestinal

GLP-1

Glucagon-like peptide-1

GTT

Glucose tolerance test

GWAS

Genome-wide association studies

HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

IFG

Impaired fasting glucose

IGT

Impaired glucose tolerance

LM

Left main

MI

Myocardial infarction

NCEP

National Cholesterol Education Program

NHLBI

National Heart Lung Blood Institute

PCI

Percutaneous coronary intervention

PPAR

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

STEMI

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

TG

Triglyceride

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) significantly increases risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the most frequent cause of death in patients with DM. Coronary disease in diabetic patients is often more complex, more widespread, and more diffuse, making revascularization options complicated. Patients with DM also suffer from an array of microvascular and macrovascular complications. However, the increased cardiovascular risk seen in these patients can be modified by lifestyle interventions, as evidenced by several large clinical trials. The cardiologist needs to be familiar with medical therapy for diabetes, as well as how DM affects management of established cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risks.

Definitions and Classifications

Classification of DM

Diabetes can be separated into four major classes based on causes and mechanisms:

Type 1 diabetes (DM1) results from destruction of pancreatic beta-cells, which make insulin. Often, this is due to autoimmune response following a viral infection. Because the cause of diabetes is absolute lack of insulin, type 1 diabetics generally require insulin.

Type 2 diabetes (DM2) results from a combination of insulin resistance and impaired beta-cell function. Historically, insulin resistance had been considered the primary defect in DM2. However, recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified genetic variants associated with DM2 that appear to affect beta cell function, suggesting the importance of the insulin secretory response in DM2.

Gestational diabetes is diagnosed during pregnancy. Gestational diabetes generally resolves following pregnancy, but women who have had it are more likely to develop DM2 later in life than those who have not.

Other medical causes include pancreatic tissue destruction (for example, from cystic fibrosis, pancreatic tumors, or surgery), medications (particularly for HIV-1 infection and organ transplantation), and genetic defects (in beta cell function or insulin secretion or action).

Diagnosis of DM2

According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), a person can be diagnosed with DM2 in any one of four ways [1].

1.

Classic symptoms

Classic symptoms include polyuria, polydipsia, and unexplained weight loss. Because these are nonspecific, these symptoms need to be associated with a random blood glucose >200 mg/dL. Other symptoms include increased appetite, fatigue, and blurry vision.

2.

Fasting glucose (Table 7-1)

Table 7-1

Fasting glucose levels

Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL) | Diagnosis |

|---|---|

≤100 | Normal |

100–125 | Impaired fasting glucose (IFG) |

>125 | Consistent with diabetesa |

A fasting glucose level after at least an 8 h fast >125 mg/dL on more than one occasion

3.

Glucose tolerance test (Table 7-2)

Table 7-2

Oral glucose tolerance test results

2-h glucose (mg/dL) | Diagnosis |

|---|---|

<140 | Normal |

140–200 | Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) |

≥200 | Consistent with diabetesa |

In an oral glucose tolerance test (GTT), fasting blood glucose is measured after an overnight (8 h) fast. 75 g glucose, usually provided in a standardized flavored solution, is administered, and blood sugar is again measured at 2 h. If the 2 h blood sugar is over 200, the result is consistent with DM2.

4.

Hemoglobin A1c (Table 7-3)

Table 7-3

HbA1c levels

HbA1c (%) | Diagnosis |

|---|---|

≤5.7 | Normal |

5.7–6.5 | Prediabetes (by HbA1c) |

≥6.5 | Consistent with diabetesa |

Glycosylated hemoglobin, or hemoglobin A1c, reflects the average blood sugar of the past two to three months. In 2010, the ADA added HbA1c criteria for the diagnosis of DM2. HbA1c of 6.5 % or higher is consistent with DM2.

Generally, the diagnosis of diabetes is not based on a single blood test on one occasion, and is most confidently made when two tests, done on separate occasions, are both consistent with DM2.

Prediabetes

Prediabetes is an imprecise term, which reflects increased risk for diabetes, or an intermediate step in the progression to diabetes. Using the same tests listed above for diabetes, there are diagnostic criteria that can be used to define prediabetes.

1.

Fasting glucose

A normal fasting glucose is ≤100 mg/dL. A fasting glucose >125 mg/dL is consistent with DM2. The intermediate range, 100–125 mg/dL is neither normal nor diagnostic for DM2. The precise term for these intermediate values is impaired fasting glucose (IFG).

2.

Glucose tolerance

On a GTT, a two hour glucose <140 mg/dL is considered normal. A two hour glucose of 200 mg/dL is consistent with DM2. The intermediate range, 140–200 mg/dL is neither normal nor diagnostic for DM2, The precise term for these intermediate values for the two hour glucose in a GTT is impaired glucose tolerance (IGT).

3.

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)

HbA1c of ≤5.7 % is considered normal. HbA1c ≥6.5 % is consistent with DM2. A value between 5.7 and 6.5 % is neither normal, nor consistent with DM2, and may be considered a sign of prediabetes.

These three definitions are based on different tests. A person could have both IFG and IGT, IFG but not IGT, or IGT but not IFG. Similarly, intermediate HbA1c values suggestive of prediabetes may or may not be associated with IFG or IGT. To be precise, the test that indicates someone has prediabetes should be specified.

Metabolic Syndrome

Definition

The metabolic syndrome refers to the co-occurrence of several known cardiovascular risk factors, including hyperglycemia/insulin resistance, obesity, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and hypertension [2]. There are several overlapping definitions for the metabolic syndrome. The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Adult Treatment Panel III (ATPIII) devised a definition for the metabolic syndrome, which was updated by the American Heart Association (AHA) and National Heart Lung Blood Institute (NHLBI) in 2005. According to this definition, metabolic if three or more of the following five criteria are met [3]:

waist circumference over 40 in. (men) or 35 in. (women)

blood pressure over 130/85 mmHg

fasting triglyceride (TG) level over 150 mg/dL

fasting HDL cholesterol less than 40 (men) or 50 (women) mg/dL

fasting blood sugar over 100 mg/dL

Medical therapy for any of the above meets the criteria, even if the current treated value of the patient does not. Thus, a person taking an antihypertensive medication meets the blood pressure criteria, even though his blood pressure may be less than 130/85. Similarly, a person taking gemfibrozil for hypertriglyceridemia meets the TG criteria even if her treated value may be less than 150 mg/dL.

Importantly, atherogenic dyslipidemia is represented twice in these five criteria, once for low HDL and once for high TG. Furthermore, the definition of metabolic syndrome does not include specific values of LDL cholesterol. People with overt DM2 by definition meet the blood sugar criteria, but may not have metabolic syndrome if they do not meet at least two additional criteria.

Epidemiology

Over 50 million in the US have metabolic syndrome

Prevalence increases with age; prevalence is 24 % over age 20, and >30 % over age 50

Clinical importance

The metabolic syndrome is important for several reasons. First, it identifies patients who are at high risk of developing atherosclerotic CVD and overt DM2. Metabolic syndrome increases risk for CVD by twofold [4–6], and risk of DM2 fivefold [7]. Second, by considering the relationships between the components of metabolic syndrome, we may better understand the pathophysiology that links them with each other and with the increased risk of CVD [2, 8].

Prevention of Diabetes

Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS) [9]

Question:effectiveness of lifestyle intervention

Subjects:522 non-diabetic overweight/obese subjects with mean body mass index (BMI) of 31 and IGT

Design:randomization to intervention (dietary and exercise counseling) vs. control

Follow-up:4 years

Result:Incidence of DM2 was 11 % in intervention group as compared with 23 % in control group (p < 0.001), a 58 % reduction

Conclusion:dietary and exercise counseling reduces the development of DM2 (and or slows the progression to DM2) in people at risk (overweight and IGT)

Diabetes Prevention Program [10]

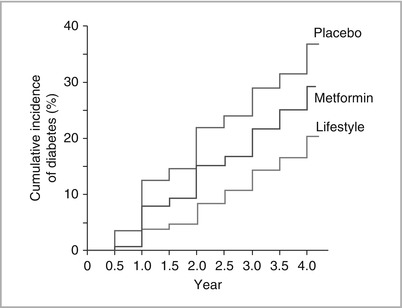

Question:lifestyle intervention vs. metfomin vs. placebo (Fig. 7-1)

Figure 7-1

Lifestyle intervention compared with metformin and placebo in the prevention of DM2.

Subjects:3,234 non-diabetic subjects with mean BMI of 34 and IFG or IGT

Design:randomization to placebo, metformin, or lifestyle modification (>7 % wt loss and >150 min exercise/week)

Follow-up:3 years

Result:Lifestyle modification was associated with 58 % reduction in development of diabetes (4.8 cases per 100 person-years), and metformin was associated with 31 % reduction (7.8 cases per 100 person-years) as compared with placebo (11.0 cases per 100 person-years).

Conclusion:lifestyle modification was more effective than metformin, though both reduced development of DM2 in people at risk (weight and IFG or IGT).

Effectiveness of Medications in Preventing DM2

Several studies show effectiveness of specific medications in preventing DM2.

STOP NIDDM [11] showed that acarbose resulted in a 25 % relative risk reduction in development of diabetes compared with placebo

TRIPOD [12] showed that troglitazone resulted in a 56 % risk reduction in development of DM2

DREAM –Ramipril [13] showed that rosiglitazone was associated with 60 % reduction in new DM2 in subjects with IGT, though ramipril did not have an effect

ACT-NOW [14] showed benefit of pioglitazone.

Treatment of Hyperglycemia

Treatment Targets

HbA1c

The most important endpoint for assessing glycemic control is the HbA1c, since it integrates long term glycemic control, does not vary moment to moment, and does not depend on fasting state. While a normal HbA1c is less than 5.5, most physicians aim for a target HbA1c of 7.0 in patients with DM2. In the ACCORD study (see below), intensive glycemic control targeting a HbA1c of 6.4 or below resulted in higher morbidity and mortality, in part due to hypoglycemia. Thus, HbA1c of 7.0 serves as a reasonable goal for glycemic control in most patients, with the exception of extremely motivated patients and those who are better able to manage possible hypoglycemic episodes.< div class='tao-gold-member'>Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree