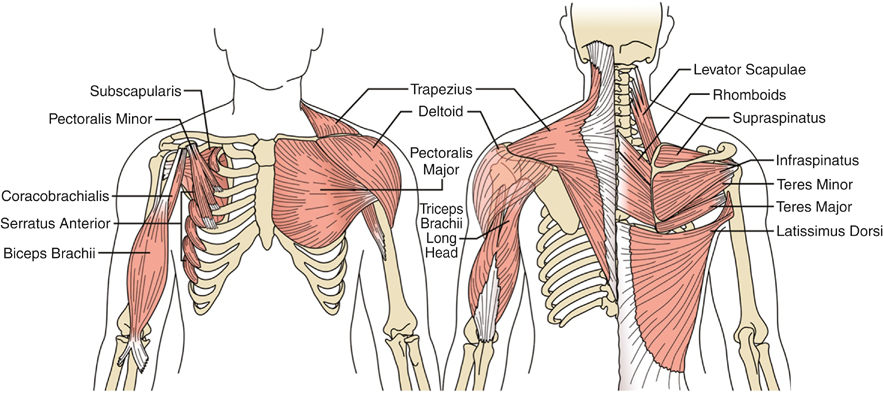

After completing the history and physical examination it is best to observe the patient’s posture with sitting and standing. Many forms of thoracic outlet syndrome manifest with asymmetry of scapular position and function. The shoulder girdle is a complex integrated system that holds the shoulder joint stable while positioning the upper extremity. For the shoulder to move back, up, or down there are balancing muscles in opposing directions (Figure 1). If one muscle is not functioning, other muscles are recruited to perform abnormal functions, which can result in many of the patient’s symptoms. A consistent finding in many patients is a depressed scapula that is rotated anteriorly. Here the pectoralis minor muscle is foreshortened and pulls the scapula down and forward. Large breasts or heavy chest walls can produce the same effect. Other muscles that are recruited in these cases include the rhomboids, the levator scapulae, and the pectoralis minor.

Many patients who are observed in the office have no loading on the upper extremity, and therefore symptoms might not be present. Gentle resistance of external rotation can bring out the additional symptoms of muscle dysfunction. If scapular dysfunction does exist, the aim in the early phase of treatment is to reestablish normal scapular function and movement. Early strengthening is not generally recommended because it can exacerbate the symptoms. Cervical, thoracic, and first rib mobilizations along with scalene and pectoralis minor stretches are important.

There are other remote causes of thoracic outlet syndrome, wherein the structure of the thoracic inlet becomes modified to compensate for changes in movement patterns. Physical therapy must be tailored to alleviate the net effect of these changes. In the authors’ experience, 49 of 55 patients evaluated for physical therapy for thoracic outlet from 2010 to 2013 had at least one of the following seven findings: (1) widespread hypermobility, (2) heightened nociceptive response, (3) abdominal scars, (4) lower extremity abnormalities, (5) lumbar dysfunction, (6) significant dental history, or (7) whiplash injury.

Physical therapy should address how the accumulation of repeated trauma has modified the patient’s posture and related movement patterns. Manual therapy may include myofascial release for manipulation, muscle energy techniques, and movement patterns before initiating any specific strengthening or stretching program. Without structural changes, strengthening and stretching just exaggerate the compensatory movement patterns.

Hypermobility is common in these patients. Stretching and soft tissue mobilization are sometimes appropriate. However, if the body senses movement outside its comfort zone, the patient’s symptoms are exacerbated and protective muscle responses such as tightening or splinting occur. Mechanically releasing tight muscles might feel good temporarily, but it can ultimately make the patient’s shoulder less stable. A heightened nociceptive response is a physical presentation of the trigger startle response. A positive result includes heightened sensitivity to palpation of a specific muscle group, some of which include the quadratus lumborum, sternocostal joints, pectoralis minor, rotator cuff muscles, scalenes, rectus capitis, posterior minor, masseter, and temporalis muscles. Until this response is down-regulated, the patient will not respond appropriately to soft tissue work.

Neurogenic TOS can develop from abnormal postures, in which the head is anterior to the thorax and the scapulas are abducted and the shoulders are internally rotated. This can increase the compression on the nerves between the scalene and the first rib and beneath the pectoralis and coracoid muscles (Figure 2). Such abnormal postures are associated with muscle shortenings that exacerbate the problem. Similarly, a patient with abdominal scars might pull the torso forward, having the head and shoulders compensate in an abnormal way. Likewise, a slight flexion of the chest can create this abnormality.

Only gold members can continue reading.

Log In or

Register to continue

Related

![]()