significant if paradoxic embolization occurs through the opening.

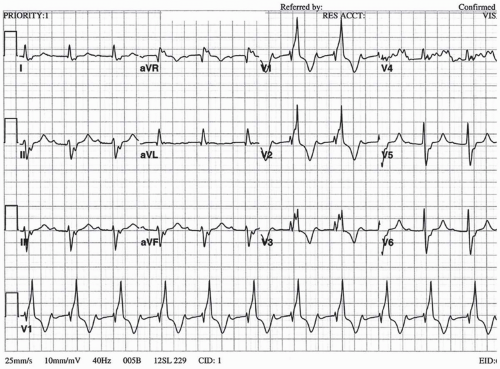

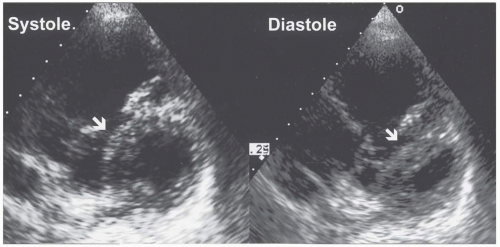

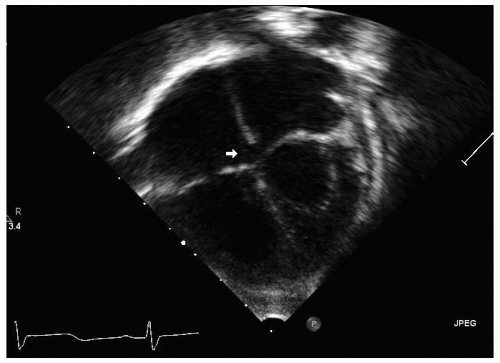

FIGURE 36.1. Apex down apical four-chamber view demonstrates a small primum atrial septal defect (arrow). |

of the right and left ventricles that cause physiologic splitting (2). If pulmonary hypertension is present, the pulmonic component of S2 may be loud and even palpable in the second left intercostal space. Because of increased pulmonary flow, a pulmonic systolic ejection murmur is present and often incorrectly assumed to represent an “innocent” murmur. Although common in children, a tricuspid diastolic flow rumble is rarely appreciated in adults. No murmur is produced by flow directly across the ASD because the interatrial pressure difference is small, and velocity of flow is low (Table 36.1).

TABLE 36.1. Clinical symptoms, signs, and evaluation of the adult with congenital heart disease | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

pulmonary hypertension is not present. However, supraventricular arrhythmias occur more commonly during pregnancy and can complicate the care of these patients (9). Atrial arrhythmias, especially atrial fibrillation, are common in these adults, occurring in 10% of 40-year-olds with unrepaired ASD, and increase the risk of paradoxic embolization. Operation, especially when performed in patients older than 40, may not prevent the later development of atrial fibrillation, perhaps because of scar formation at the atrial incision site (10). In one study, moderate pulmonary hypertension (systolic pulmonary artery pressure, 40 to 60 mm Hg) developed in 26% of patients. Severe pulmonary hypertension (pulmonary systolic pressure, higher than 60 mm Hg) develops only rarely and was present in only 7% of adults, although it may manifest at a very young age, even in patients with small defects (11). In these patients, it is possible that unrelated pulmonary vascular disease (e.g., primary pulmonary hypertension) may coexist with the ASD or may be triggered by relatively small increases in pulmonary blood flow. Interestingly, development of pulmonary hypertension may occur more frequently in patients with sinus venosus ASD than in those with ostium secundum ASD (26% vs. 9%, respectively) (12). In infants with large ASD, the tendency for recurrent upper and lower respiratory tract infections is well documented. Although it is

less well documented in adults, one study of medical management versus surgical closure of ASD in adults suggested that recurrent pulmonary infections were more common in the group whose ASD was not closed (13). In older patients with significant unrepaired ASD (left-to-right shunt blood-flow ratio at least 1.5:1), right-sided heart failure may develop with peripheral edema and even ascites. Endocarditis is uncommon in patients with secundum ASD but is more common in patients with primum ASD and cleft mitral valve (Table 36.2).

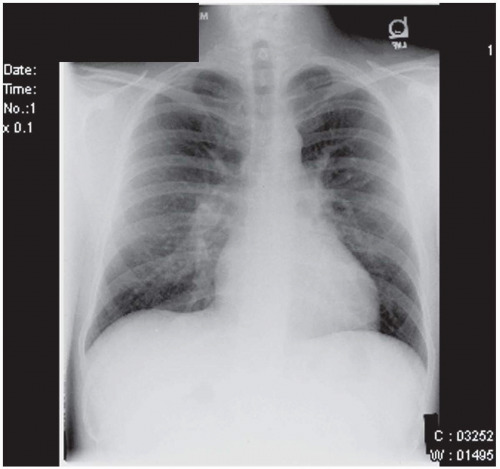

FIGURE 36.3. Chest radiograph of the same patient depicted in Fig. 36.2 with large secundum atrial septal defect, which demonstrates right ventricular enlargement and prominent peripheral pulmonary arteries, consistent with “shunt vascularity.” |

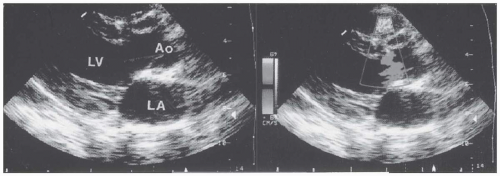

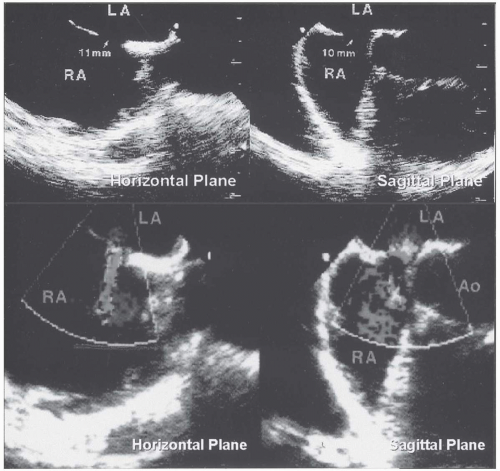

FIGURE 36.5. Transesophageal echocardiography of secundum atrial septal defect in the horizontal and sagittal planes. On color Doppler echocardiography, a left-to-right shunt was demonstrated. |

TABLE 36.2. Treatment, complications, and follow-up of adults with congenital heart disease | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

symptomatic patients with a pulmonary-to-systemic blood-flow ratio (Qp/Qs) of 1.5:1 or higher. Closure of the defect prolongs survival if performed before the age of 40 (10,11,14,15). ASD closure at an earlier age may prevent later occurrence of atrial fibrillation to some degree. However, atrial fibrillation is still frequent after repair and is associated with late stroke (10). Whether simultaneous performance of the Maze procedure for atrial fibrillation in the older patient with ASD prevents later arrhythmias is unknown. ASD closure is also recommended for asymptomatic patients younger than 40 years with a Qp/Qs of 1.5:1 or higher if right-sided heart enlargement is present, primarily for the prevention of right-sided heart failure. Closure of ASDs in asymptomatic older adults is more controversial. In one large study, 521 patients older than 40 years with secundum ASD were randomly assigned to undergo surgical closure or receive medical therapy and were monitored for more than 7 years (15). The risk of the combined end point (death, pulmonary embolism, major arrhythmic event, cerebrovascular embolic event, recurrent pulmonary infection, functional class deterioration, or development of heart failure) was higher in the medically managed group than in the surgical group (hazard ratio of 1.99; p < 0.01). Although no difference was found in mortality rate between medical and surgical groups during this period of follow-up, the authors propose surgical closure in all patients older than 40 with secundum ASD with a Qp/Qs of 1.7:1 or higher who do not have fixed pulmonary hypertension. Some patients with small secundum ASD and a history of paradoxic embolization may benefit from closure.

reduced need for blood products, and less patient discomfort. However, as with any other comparison between a surgical procedure and a transcatheter intervention, these authors acknowledged that the surgeon’s ability to close any ASD regardless of anatomy remains an important advantage of surgery. Similar results were reported in a multicenter nonrandomized study (20). The Amplatzer Septal Occluder has a low incidence of complications (21,22).

beneath the aortic valve when viewed from the left ventricle) in 70%, muscular (either single or multiple in the muscular portion of the septum) in 20%, supracristal or subpulmonic (beneath the pulmonary valve, undermining the aortic valve annulus and associated with aortic valve prolapse and insufficiency) in 5%, and inlet, or “atrioventricular canal,” defects (beneath the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve) in 5% to 8%.

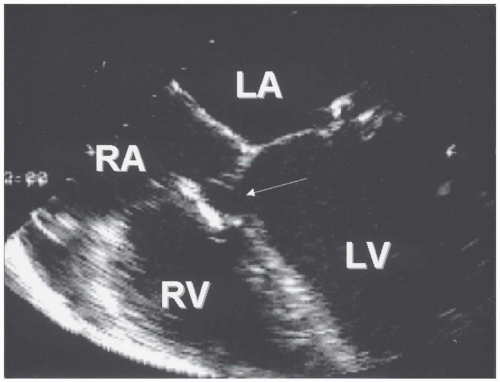

these patients may show cardiomegaly with enlarged left atrium and left ventricle (from the increased flow that returns from the lungs to the left side of the heart) and prominent central pulmonary arteries with “shunt vascularity.” In the patient with shunt reversal due to Eisenmenger physiology, the ECG shows prominent right axis shift with right atrial and right ventricular hypertrophy and possible right ventricular “strain” repolarization abnormality with QRS widening. Frequently, premature ventricular contractions are captured on routine ECG or ambulatory ECG monitoring. On chest radiograph, right-sided heart enlargement is notable, with dilated, sometimes calcified central pulmonary arteries and tapering or “pruning” of the pulmonary vessels in the periphery. On transthoracic color and spectral Doppler echocardiography, the hallmark of VSD is usually high-velocity flow from the left ventricle to the right ventricle at the site of the defect in the interventricular septum (Fig. 36.6). In some patients, a ventricular septal aneurysm forms as a result of partial or complete closure of a perimembranous VSD by portions of the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve (Fig. 36.7). The sonographer must carefully interrogate all regions of the septum from multiple views with color and spectral Doppler imaging to avoid missing small defects. Nevertheless, very small muscular VSDs with characteristic murmurs, especially if multiple, may not be visualized on transthoracic or even the more sensitive transesophageal echocardiogram. Intravenous injection of agitated saline microbubbles is not usually helpful in the diagnosis of small VSDs, because the shunt is left to right. Adults with very large VSDs and Eisenmenger physiology may have no shunt whatsoever or a small right-to-left shunt demonstrated by color or spectral Doppler imaging at the defect site. Echocardiography is also instrumental for the evaluation of additional cardiac lesions, including aortic valve prolapse and insufficiency and subpulmonic obstruction, which may develop in late adolescence or adulthood as a result of hypertrophy of the crista supraventricularis. Cine magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography may elegantly display all types of VSDs.

pulmonary vessels for evidence of irreversible pulmonary vascular obstruction.

closure of the VSD occurred in 19 patients (10%, all between the ages of 17 and 45; mean age, 27 years). Serious complications occurred in 46 patients (25%): infective endocarditis in 11%, progressive aortic insufficiency in 5%, and symptomatic arrhythmias, most commonly atrial fibrillation, in 8.5%. Irreversible pulmonary vascular obstruction (Eisenmenger syndrome) inexorably develops before adulthood in the patient with a large, nonrestrictive VSD and carries the potential for complications such as endocarditis; right-sided heart failure; hemoptysis; erythrocytosis with the attendant risks of hyperviscosity, hyperuricemia, and gout; renal insufficiency; cholelithiasis; and sudden cardiac death. Maternal and fetal mortality rates among pregnant women with Eisenmenger syndrome exceed 50% and are higher in women with pulmonary hypertension due to VSD than with that due to ASD (31). Aortic insufficiency develops in 2% to 7% of patients with VSDs over time, occurs more commonly in adults older than 20 years, and is classically associated with the supracristal or subpulmonic type of defect, although it may occur in perimembranous VSD (32). In 25% of these patients in one study, the severity of aortic insufficiency remained stable over time. Aortic insufficiency is much more common in the Asian population with subarterial VSDs, developing in 64% of 139 asymptomatic patients in one study (33). The authors of this study found that aortic prolapse and insufficiency developed only in patients with a VSD diameter larger than 5 mm and recommended closure in these patients.

with repair and should not undergo operation. At this time, no curative therapy is available for patients with Eisenmenger syndrome. Pregnancy should be strongly discouraged, and sterilization of the patient or, preferably, the sexual partner should be offered, because even minor noncardiac surgery conveys significant risk in these patients. Pregnancy termination may be considered for certain patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree