Congenital Heart Disease

This book is concerned with adult echocardiography, and so the congenital abnormalities described in this chapter are primarily those that may be encountered in adult patients, often following surgical or percutaneous correction. A detailed discussion of congenital heart disease is beyond the scope of this book, but a number of excellent reference works are available for further reading.

ATRIAL SEPTAL DEFECT

Atrial septal defect (ASD) is the commonest form of congenital heart disease seen in adults. The commonest form of defect is the secundum ASD, accounting for twothirds of cases, in which the fossa ovalis is absent, leaving a defect in the centre of the interatrial septum. Primum ASD is rarer and causes a defect in the inferior interatrial septum, often associated with a cleft anterior mitral valve leaflet. Sinus venosus ASD is also rare and is found near to where the superior or inferior vena cava joins the right atrium (RA). It is associated with partial anomalous pulmonary venous drainage, in which one or more pulmonary veins drain directly into the RA (or one of the vena cavae) instead of the left atrium (LA).

An ASD can also be acquired as a result of deliberate puncture of the interatrial septum during balloon mitral valvuloplasty or left-sided electrophysiological procedures, or accidental puncture during right heart catheterization or pacing.

Clinical features of atrial septal defect

ASD can remain asymptomatic for many years and may present late in adult life. It can also be an incidental finding. The clinical features are summarized in Table 28.1. In advanced cases, the increased pulmonary blood flow with an ASD eventually leads to pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure.

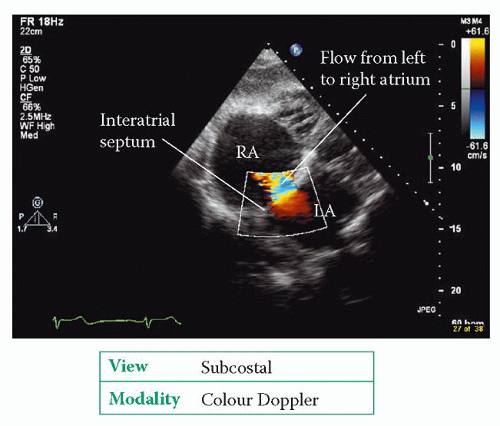

Echo assessment of atrial septal defect

The best transthoracic view of the interatrial septum is obtained from the subcostal window, although the septum can also be seen from the apical window (4-chamber view) and the parasternal window (short axis view, aortic valve level). In each view, use 2D echo to assess the structure of the interatrial septum:

Does the interatrial septum appear normal or is there any aneurysm formation (see box)?

Is there any echo dropout in the septum to indicate a defect? In the apical view, it is not unusual to see areas of ‘apparent’ dropout in the interatrial septum, which is quite a long way from the probe, so be careful not to report dropout as an ASD unless you can also see it in other views and/or you also have further supporting evidence.

Assess right atrial and ventricular size/function – are they dilated as a consequence of a left-to-right shunt? Is there evidence of right heart volume overload (paradoxical motion of the interventricular septum)?

Table 28.1 Clinical features of atrial septal defect | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Use colour Doppler to check for the presence of flow across the defect. Flow across an ASD is normally from left to right, mainly during diastole, and also in systole (Fig. 28.1).

In the subcostal view, use pulsed-wave (PW) Doppler to assess flow across the defect.

If you identify an ASD, comment on its size and location (secundum, primum or sinus venosus), and be sure to check for any associated abnormalities (e.g. cleft anterior mitral valve leaflet). Check also for the presence of tricuspid and/or pulmonary regurgitation and, where possible, assess pulmonary artery pressure in case pulmonary hypertension has developed. Perform a shunt calculation to estimate the shunt ratio (see box).

SHUNT CALCULATIONS

Normally the stroke volume of the right heart equals that of the left. However, the presence of a left-to-right shunt such as an ASD means that a portion of the blood that would normally leave the left heart with each heartbeat instead enters the right heart, and is pumped through the lungs before returning to the left heart again. Thus in the presence of a left-to-right shunt the stroke volume of the right heart is greater than that of the left, and the ratio between the two is a measure of the severity of shunting. The ratio is often referred to as Qp/Qs, where Qp is pulmonary blood flow and Qs is systemic blood flow. To calculate the shunt ratio:

In the parasternal short axis view (aortic valve level), measure the diameter of the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) in cm, then use this to calculate the cross-sectional area (CSA) of the RVOT in cm2:

In the same view, measure the velocity time integral (VTI) of flow in the RVOT (using PW Doppler) to give VTIRVOT, in cm.

In the parasternal long axis view, measure the diameter of the LVOT in cm, then use this to calculate the CSA of the LVOT in cm2:

In the apical 5-chamber view, measure the VTI of flow in the LVOT (using PW Doppler) to give VTILVOT, in cm.

The shunt ratio is the ratio of SVRVOT to SVLVOT which, in the presence of a left-to-right shunt, will be greater than 1. A significant limitation to shunt calculations is that they are heavily dependent on an accurate measurement of RVOT and LVOT diameter – as the calculation involves squaring these measurements, even a small inaccuracy in measurement can lead to a large error in the final result.

If there is doubt about the presence of an ASD, it may be necessary to perform an ‘agitated’ saline contrast study as for patent foramen ovale (PFO) (see box). Although transthoracic echo (TTE) can often detect evidence of an ASD, transoesophageal echo (TOE) will usually be required to assess an ASD in detail (or to rule out an ASD if clinical suspicion remains after a normal TTE). Sinus venosus defects can be very difficult to visualize on TTE.

ATRIAL SEPTAL ANEURYSM

Atrial septal aneurysms are thought to have a prevalence of around 1 per cent. They are defined as a bulge or deformation of the interatrial septum protruding at least 10 mm into the right or left atrium (or, if mobile, swinging by at least 10 mm from side to side) and with a diameter across their base of at least 15 mm. They have been reported to be associated with ASD and PFO (and also with mitral valve prolapse) and are also thought to be a potential cardiac source of emboli.

Management of atrial septal defect

An ASD can be closed percutaneously or surgically. Percutaneous closure is performed for secundum ASDs if there is an adequate rim of tissue around the defect to allow deployment of a septal occluder device without impinging on nearby structures. Surgical closure requires a thoracotomy to open one of the atria and suture a patch (made from Dacron or from the patient’s own pericardium) over the defect.

Echo assessment following repair

Using the same views as for unrepaired ASD:

comment on the presence of a septal occluder device or patch

check for any residual shunt

assess right heart size and function

assess pulmonary artery pressure.

ASD AND 3D ECHO

3D echo can be helpful in the assessment of congenital heart disease and has been of particular value in assessing ASDs, providing information on the morphology of the interatrial septum and the surrounding structures. It has also been used to guide device closure.

PATENT FORAMEN OVALE

In utero, the foramen ovale is a flap-like structure that permits shunting of blood directly from the RA to the LA. The flap normally closes after birth, when LA

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree