INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

In general, the presence of a congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is an indication for repair (Figs. 37.1 and 37.2). Most patients with CDH will present in the first 24 hours of life although, they can present as late as adulthood. The first reported survivor from repair in the first 24 hours of life was by Gross in 1946. It required advances in anesthesia, neonatal critical care, and mechanical ventilation before a number of infants would survive. By the late 1960s, centers were reporting the survival of -50% in infants with CDH. Surgical repair was traditionally performed via a laparotomy or thoracotomy until the advent of minimally invasive surgery in infants. The timing of repair was generally considered a surgical emergency until the late 1980s when reports of delayed repair were first seen. It is now rare that a CDH is repaired in the first 6 to 12 hours of life, and many are repaired after 5 days of life. Contraindications to repair would include fatal chromosomal anomalies such as trisomy 13 and 18. While not an absolute contraindication, survival in infants with single ventricle physiology is so poor that many would not routinely offer surgical correction to these patients.1 Prematurity is not a contraindication and successful repair has been performed on infants who were 26 weeks’ gestational age.2

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Operative repair of a CDH should be performed when the patient is medically stable. This definition varies amongst centers. In the patient who is not on extracorporeal life support (ECMO), we plan for operation when the patient does not require significant ventilator support (peak inspiratory pressures <25, FiO2 < 0.5) with preductal oxygen saturations over 90. Ideally, the pulmonary hypertension has resolved, but this may not always occur. If the patient is on ECMO, we will usually operate within the first 24 to 48 hours on ECMO unless the patient is significantly edematous in which case we delay until the infant is at dry weight.3

Figure 37.1 External view of a congenital diaphragmatic hernia in a newborn. Note the barrel-shaped chest and scaphoid abdomen.

The location for repair will depend on the patient’s stability. If the patient is not on ECMO or high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV), we will often plan for repair in the operating room. If the patient is on ECMO, repair is performed in the intensive care unit as transport on ECMO can be difficult. Patients on ECMO receive aminocaproic acid as a loading dose 1 hour before operation, and this is continued for 36 to 48 hours after repair.4 We also make liberal use of the argon cautery when doing repair on ECMO.

Planning

• Repair on minimal ventilator support

• Repair ideally when pulmonary hypertension is resolved

• Early repair with aminocaproic acid if on ECMO

SURGERY

SURGERY

There are several operative approaches to the repair of a CDH. Repair can be done via an open laparotomy or thoracotomy or using minimally invasive techniques via laparoscopy or thoracoscopy. We approach the open repair via a subcostal incision and a minimally invasive repair via thoracoscopy.

Figure 37.2 Chest x-ray of a congenital diaphragmatic hernia in a newborn. Bowel loops are noted in the left chest (arrow).

Figure 37.3 Retraction of the anterior lip of the diaphragm and mobilization of the posterior lip during manipulation of the bowel back into the abdomen.

Open Repair

Positioning

Patients are placed in the supine position with a small shoulder roll on the side of the defect. It is important to assure the chest is in the sterile field in the rare instance when a thoracotomy may be needed to help reduce the contents. This is more likely to occur with right-sided defects.

Technique

We use a broad subcostal incision approximately 2 cm below the costal margin. Once the abdomen is entered, the bowel is carefully manipulated from the chest into the abdomen. It may occasionally be difficult to get the spleen down. In that instance, using a vein retractor on the anterior edge of the diaphragm and gentle traction on the stomach can be helpful. In patients who are not on ECMO, the posterior lip of the diaphragm is mobilized (Fig. 37.3). This dissection is minimized in patients on ECMO due to the bleeding risk.

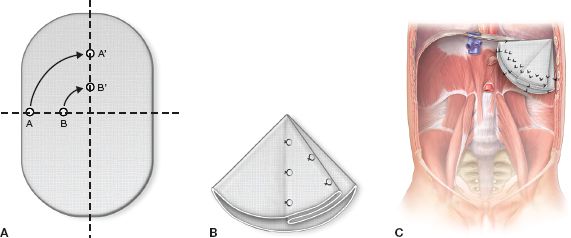

Primary repair can be performed using pledgeted 2-0 polyester suture or silk sutures (Fig. 37.4). We use the 1 mm polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) soft tissue patch for those patients who require a patch repair. We create a cone-shaped patch by taking pleats in the patch as it is sewn to the edges of the diaphragm or ribs (Fig. 37.5). Alternatively, the patch can be preformed and then sewn in place.5 This allows for improved pulmonary compliance postoperatively and a potentially decreased risk of recurrent herniation. The defect size can be quite variable and very larger defects may be a challenge to repair. The defect should be characterized into one of four standardized classes (A to D) (Fig. 37.6).

Figure 37.4 Primary repair using silk suture (pledgeted polyester can be used as well).

Figure 37.5 A: Pleating the PTFE patch. B: Cone folded from PTFE patch and fixed with stitches. C: Cone-shaped patch sewn into CDH defect.