INTRODUCTION TO ABNORMAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE RESPIRATORY TRACT

Learning Objectives

The student will be able to describe the anatomical and/or physiological abnormalities underlying major congenital malformations of the lungs.

The student will be able to identify useful indices of pulmonary function to assess severity of impairment based upon a history and description of the patient.

The student will be able to tabulate the relative values of the history, physical exam, bronchoscopy, and imaging modalities to establish the likelihood of specific anomalies at different locations within the respiratory system.

Accurate and timely identification of congenital anomalies often makes the difference between an infant’s survival and death. Such respiratory system defects also illustrate how physicians must carefully choose among many diagnostic modalities available to most effectively and appropriately arrive at a diagnosis and treatment plan. History obtained from caregivers, and a physical exam tailored to the very young patient (Chap. 14), often only point to the need for more advanced diagnostic procedures. While direct visualization is possible with some lesions, diagnostic imaging is often essential. Each diagnostic modality carries with it a unique risk/benefit assessment. Radiography can be helpful, particularly when contrast studies are feasible (Chap. 15), but the latter creates risks of aspiration injuries. Endoscopy or bronchoscopy are often the definitive modalities in specific anatomical regions, notably in the trachea and upper airways (Chap. 18), but these may not be necessary before an operative assessment and intervention. Marked advances in computerized imaging such as CT have led to improved diagnostic accuracy of lesions found at all levels of the respiratory tract. They are most useful in delineating the scope of suspected parenchymal anomalies (Chap. 15), including those in which the traditional boundaries between the conducting and respiratory zones are blurred by the presence of unanticipated structures. Throughout this chapter, the relative values of these diagnostic tests will be emphasized for each type of anatomical deviation from the normal pattern of lung development.

CONGENITAL DEFECTS OF THE LARYNX

Suspicions regarding defective laryngeal anatomy often arise during the physical exam with stridor, chest retractions, and respiratory distress readily visible. Direct visualization may reveal the lesion during attempted intubation to secure the child’s airway, whereas imaging modalities often add little unless contrast is used to confirm aspiration events or a para-laryngeal mass is suspected. Use of a rigid endoscope is the preferred means of confirming laryngeal clefts (see below).

Bifid epiglottis is a rare lesion characterized by a midline cleft in the epiglottis. Patients may be asymptomatic or have feeding difficulties with aspiration. Direct visualization of this lesion is the only means of diagnosis. Specific therapy is rarely needed.

Laryngeal atresia is the most catastrophic anomaly of the airways in the newborn. This extremely rare lesion results from failed recanalization of the laryngeal orifice in utero. There is usually no specific cause identified. Depending upon the time of the developmental arrest, both the subglottic and supraglottic structures may be involved. At birth, the neonate has immediate, severe respiratory distress with sternal and costal retractions, and may exhibit extreme respiratory efforts but no detectable airflow. Emergent tracheostomy is required for survival. Diagnosis is most often made at postmortem examination, but may be recognized during attempted laryngeal intubation.

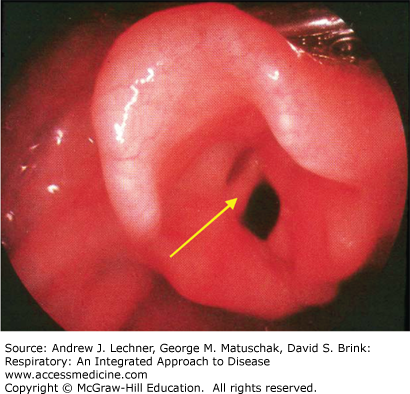

Laryngeal webs result from partial failure of recanalization of the larynx (Fig. 37.1). A web is usually a relatively thin and incomplete membrane, with the posterior aspect of the glottis open. The presentation of a laryngeal web depends upon its extent. Most patients present in the neonatal period with stridor, weak or absent cry, and respiratory distress. However, patients with a larger glottic opening may present much later, with symptoms only seen at exercise or simply with hoarseness. Diagnosis is made by laryngoscopy. Treatment varies with the extent, position, and thickness of the web.

Laryngotracheoesophageal (LTE) clefts are rare lesions in which there is direct communication between the trachea and esophagus starting at the larynx. A type 1 lesion involves only the inter-arytenoid musculature, and presents with weak cry and stridor that may be indistinguishable from laryngomalacia (see below). If the type 1 lesion renders the larynx incompetent, the affected child may aspirate or have feeding difficulties. Type 2 lesions extend through the cricoid cartilage, and type 3 lesions extend into the trachea. The latter render the larynx incompetent, with infants presenting with a weak cry and stridor that are usually accompanied by massive aspiration. Early diagnosis of any LTE cleft is important to prevent the serious respiratory complications of aspiration. The radiological demonstration of a “high” aspiration during a barium swallow exam leads to more specific diagnostic testing. Direct laryngoscopy with the ability to manipulate the arytenoids is the primary diagnostic technique. A cleft may be missed if only a flexible endoscope is used to inspect the larynx, since the cleft may not be readily apparent without separating the arytenoids. Associated anomalies occur in about 60% of cases, usually involving the gastrointestinal tract or other levels of the respiratory tract. The presence of these abnormalities may lead to the evaluation of airway abnormalities, such as in the child with Opitz G/BBB syndrome (hypertelorism, prominent occiput and forehead, posteriorly rotated ears, stridor, hoarse cry, and genital anomalies) who should be suspected of having an LTE cleft until proven otherwise. Treatment is surgical and may require temporary tracheostomy. LTE clefts that extend to the carina or beyond are difficult surgical cases but have been successfully repaired when supported by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

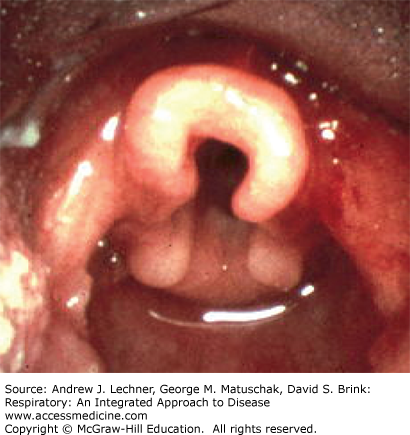

Laryngomalacia (congenital laryngeal stridor) is the most common laryngeal abnormality. It is considered to be more of a functional than an anatomic abnormality of the larynx as supraglottic structures prolapse into the airway during inspiration. The epiglottis often has a characteristic omega shape (Fig. 37.2), or the arytenoids may be large, with short arytenoid-epiglottic folds but are most notable for the tendency to prolapse over the vocal folds. The most common clinical presentation is that of an otherwise healthy child in no respiratory distress making a characteristically harsh inspiratory noise that varies with activity. This noise is often high-pitched with a fluttering character. If severe, laryngomalacia may result in failure to thrive due to feeding difficulties or cyanotic episodes due to airway obstruction. The diagnosis is most often made on clinical grounds, that is, by history and exam, and in the otherwise thriving child this is often sufficient. The natural history of laryngomalacia is variable, but most children outgrow the abnormality in their second year of life. If airway obstruction is severe, surgical therapy may be necessary.

TRACHEAL ANOMALIES

As the greatest length of the trachea is intrathoracic, the most common finding on physical exam is wheezing. However, less compliant abnormalities may only become apparent when the child is exertional with crying or a bowel movement. In this situation, airflow may cease and the child becomes cyanotic. Tracheal lesions are seen well by bronchoscopy, which provides useful information about their dynamic properties during breathing. Imaging by CT or MRI with reconstruction of serial airway sections is very useful in assessing the distal extension and caliber of tracheal stenosis and/or the position of surrounding structures that may be impinging on the trachea.

Tracheal agenesis presents as immediately and catas-trophically as laryngeal atresia. It is extremely rare, with fewer than 50 cases reported. One may detect the absence of a trachea below the larynx in the neck by palpation, and intubation will be impossible. The etiology of this lesion is unknown but there is a high incidence of associated severe anomalies. At present there is no effective treatment that ensures long-term survival.

Congenital tracheal stenosis is an uncommon lesion of intrinsic narrowing of the trachea (Fig. 37.3). It is most often due to the absence of the posterior membranous portion of the trachea, resulting in tracheal walls completely encircled by cartilaginous rings. Stenosis may involve short tracheal segments, or involve the entire extent of the trachea. Its etiology is unknown since there is no period in normal development when complete tracheal rings are present. Patients may present throughout the first years of life, typically with symptoms of recurrent wheezing unresponsive to bronchodilators, depending on the severity of the stenosis. The narrower the stenosis, the younger is the age (hence size) when symptoms present. Symptoms are nonspecific and require a high index of suspicion to proceed to further diagnostic evaluation. The diagnosis may be suggested by plain chest radiograph, with CT and bronchoscopy further defining the abnormality. Short segment stenosis can be successfully treated by excision, but longer stenoses are more problematic. Increasing the tracheal lumen has been attempted by inserting a variety of graft materials to act as stents, including cartilage and pericardial tissue. However, a more recently developed surgical technique called the “slide tracheoplasty” that preserves the native trachea, has become the standard surgical intervention with good success in less extensive lesions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree