LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Learning Objectives

The student will be able to conduct a basic chest exam on standardized or real patients using modalities of inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation.

The student will be able to make valid diagnostic inferences from the findings of a basic chest exam, including interpretation and application of likelihood ratios.

Physical examination of the patient’s chest adds valuable information to direct clinicians toward a correct diagnosis when symptoms suggest a lung disease or disorder. This chapter summarizes first the key elements of a basic chest exam, using the four modalities of inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. It then gives guidance on interpreting those findings, using estimates of the discriminatory power of certain results, or their absence, by means of positive likelihood ratios (+LR) or negative likelihood ratios (−LR). It is important to note that students must practice the chest exam on standardized patients and real patients. Such practice should be augmented with breath sound simulators, a valuable way to become familiar with abnormal lung and adventitious sounds that standardized patients usually do not have.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Although this chapter focuses on the basic chest exam, assessing all vital signs is crucial in patients who present with symptoms that suggest a lung disease or disorder. Here, four modalities are discussed in succession. In practice, most physicians first evaluate the patient for any signs of respiratory distress including use of accessory muscles of respiration, then examine the posterior chest and lung fields using all four modalities, and finally examine the anterior chest wall and lung fields using all modalities. The posterior chest wall is best examined with the patient sitting erect on an exam table or hospital bed. Even frail, bedridden patients can generally be safely held in a sitting position by assistants, while the physician examines the posterior chest and lung fields. Some experts recommend examining the anterior chest wall with the patient sitting, while others prefer that the patient be supine for the anterior chest exam, so that a female patient’s breasts may be gently displaced.

The lungs are nearly symmetrical structures, and except for the lower anterior chest wall where the heart intervenes, each side serves as a natural control to the other. Indeed, a proper chest exam carefully evaluates any side-to-side asymmetries. The exam should not be made through a hospital gown, since this can alter the findings of all four modalities. Physicians can learn to respect patient modesty while completing a thorough exam.

INSPECTION

There are four questions to be answered during the inspection phase of the chest exam:

Is the patient using the accessory muscles of respiration?

Is the trachea deviated from a midline position?

Are there any chest wall structural abnormalities such as kyphosis or scoliosis?

Is chest expansion of the two hemithoraces symmetric, or asymmetric?

Observe the patient’s neck during several breathing cycles, especially the sternocleidomastoid and scalene muscles, noting whether these muscle groups are participating in inspiration. Under normal circumstances, patients do not manifest inspiratory contraction of the accessory muscles.

Use of accessory muscles is a sign of acute respiratory distress and/or significantly reduced pulmonary reserve, correlating with an FEV1 <70% of predicted values. Hence, accessory muscle use is usually accompanied by an increased respiratory rate (ie, tachypnea). Even so, accessory muscle use is not specific to the type of underlying respiratory system disorder.

Using a ruler and the medial ends of the clavicles as reference points, determine whether the trachea is equidistant between the ends. If it is not midline, observe whether there is a visible neck mass.

Normal tracheal position is from exact midline up to 4 mm to the right of midline. A trachea even 1 mm to the left of the midline is left-deviated. A trachea that is more than 4 mm to the right of midline is right-deviated. Tracheal deviation is due to a neck mass, a superior mediastinal mass, or significant unilateral chest pathology. This differential diagnosis is resolved as follows. If there is no visible neck mass, proceed with completing the chest exam. If further exam demonstrates no major unilateral abnormality, then imaging studies of the superior mediastinum are indicated to confirm and delineate the process.

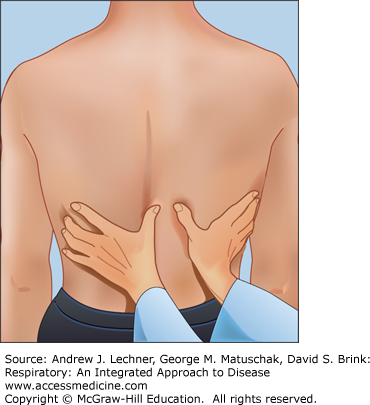

While standing behind the patient, the physician’s hands are placed at the level of the patient’s 10th ribs, with fingers pointed laterally and parallel to the ribs, and thumbs placed medially (Fig. 14.1). Then the physician’s hands are slid medially to raise a small amount of loose skin between them, while keeping the thumbs 2-4 cm apart on the respective hemithoraces. The patient is instructed to take several deep breaths as the physician’s thumbs are noted for symmetric or asymmetric movement.

While standing behind the patient who is looking straight ahead, the physician places her left and right hand on the patient’s left and right lateral chest walls. The patient is instructed to take several deep breaths, while the physician observes both the motion of her hands and the force exerted on them by the patient’s chest wall. Asymmetry in either the extent of hand movement, or the force exerted upon them, is an abnormal finding.

Asymmetric movement indicates a unilateral pathology on the side with less movement. Symmetric expansion has no diagnostic value, since it occurs in normal persons, patients with diffuse lung diseases, and many with unilateral pathologies. Thus this test is specific for unilateral pulmonary pathology, but it lacks sensitivity.

PALPATION

There is one question being asked during palpation of the chest: Is fremitus in this patient symmetric?

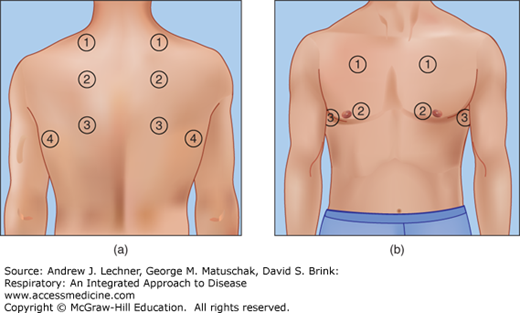

Fremitus, also called tactile fremitus or vocal fremitus, refers to vibrations produced by the patient’s speech that are detected when the physician’s hands are placed on the patient’s chest wall. The examiner instructs the patient to repeat a brief expression, such as “ninety-nine”, or “toy boat”. As the patient complies, the examiner systematically surveys the chest wall for vibrations, always comparing one side to the other for evidence of asymmetry. For optimal detection of vibrations, some physicians use the ulnar surface of their hand or fifth digit, while others employ the palmer surface that overlies the distal end of metacarpal bones 2-5. Some clinicians test for fremitus using both hands simultaneously to compare the two sides, whereas others prefer a systematic survey of the chest wall with one hand. If using the one-handed technique, a sequential ladder pattern (Fig. 14.2) ensures that comparisons at each site are immediately preceded or followed by their mirror images from the opposite hemithorax.

There is considerable variation in the prominence of detected fremitus among healthy subjects and patients, and thus it is not a useful modality when comparing individuals. The method is more sensitive to lower-frequency vibrations than to those of higher frequency, and so fremitus tends to be more prominent in men than women. Diagnostically, physicians expect fremitus to be symmetric in an individual patient, and any detected asymmetry is an abnormal finding. An area of asymmetry is then evaluated to determine whether its fremitus is increased or decreased relative to a presumptively normal area on the patient’s other side. This distinction is best made by comparing the asymmetric regions to other adjoining regions. Decreased fremitus can occur in any disease that places a material other than normal lung against the inner chest wall, thus decreasing transmission of vibrations to the physician’s hands. Thus, decreased fremitus is associated with an ipsilateral (same-side) pneumothorax, pleural effusion, pleural scarring, or tumor mass adjacent to the chest wall. Increased fremitus, in most cases, indicates the presence of the consolidation of pneumonia.

PERCUSSION

Three questions need to be answered during the percussion phase of the chest exam:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree