Concomitant Renal and Aortic Pathology

TIMOTHY K. WILLIAMS and W. DARRIN CLOUSE

Presentation

A 65-year-old male presents to his primary care physician for complaints of recent onset of lower extremity edema, mild shortness of breath, and severe headaches. He has a medical history significant for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and a smoking history of 50 pack-years. He quit 5 years ago. There is no history of coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, or diabetes. Upon further interrogation, the patient reports new-onset dyspnea on exertion and generalized fatigue but denies chest pain.

His current medications include a statin and three antihypertensive medications, including a beta-blocker, diuretic, and angiotensin receptor blocker. Physical exam in the office is notable for a blood pressure of 210/140 mm Hg, whereas previous outpatient encounters have shown good blood pressure control. There are fine crackles at the bilateral lung bases. Auscultation of the abdomen reveals a harsh bruit. The aortic pulsation is easily palpated and seems widened despite mild truncal obesity. There is moderate bilateral lower extremity pitting edema. Peripheral pulses are easily appreciated.

Differential Diagnosis

This patient’s presentation is consistent with hypertensive crisis and hyperaldosterone state manifesting with headaches, evidence of pulmonary edema, and volume overload. In this clinical scenario, it is imperative to recognize the acute severity of this condition and need for immediate blood pressure control and expedited evaluation. Hospital admission is appropriate and essential to minimize the risk of end organ dysfunction.

While patients with essential hypertension commonly require several medications for appropriate control, the presence of severe and abruptly worsening hypertension raises concern for secondary etiologies, particularly in the context of continued medication compliance. The differential diagnosis for secondary hypertension includes adrenal cortical tumors, pheochromocytoma, hyperthyroidism, acute cocaine or amphetamine intoxication, and a variety of intrinsic renal pathologies in addition to renovascular disease.

While endocrine diseases and intrinsic renal cortical entities, such as polycystic kidney disease and the spectrum of nephritides and small-vessel vasculitides, are important causes of secondary hypertension, the vascular surgeon’s focus in assessing these patients should be the identification of reversible renovascular pathologies requiring intervention. These include atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis, fibromuscular dysplasia, and renal artery dissection, with the former being the more commonly encountered pathology.

In this patient with clear atherosclerotic risk factors, additional physical exam findings suggest complex and/or concomitant vascular pathology. The finding of a harsh abdominal bruit in conjunction with this clinical history strongly suggests the presence of renal artery stenosis. Furthermore, with a strong history of smoking and the presence of an easily palpable aortic pulsation, an abdominal aortic aneurysm should be suspected as well.

Workup

The patient is admitted to the hospital on the medicine service and is placed on intravenous antihypertensive agents, with adequate reduction in his blood pressure. His headache resolves and overall feels better. Echocardiography indicates normal ventricular function with a mildly hypertrophic left ventricular wall. He is managed with volume restriction and gentle diuresis for his pulmonary edema. However, laboratory analysis reveals an elevated serum creatinine at 2.5 mg/dL, increased from his previous baseline of 0.9 3 months ago. Serum and urine markers for various endocrine etiologies of secondary hypertension are obtained, which are unremarkable. Given suspicion for vascular pathology, the vascular surgery service is consulted to evaluate the patient. As the vascular consultant, you are asked to recommend additional diagnostic tests.

There are multiple diagnostic modalities that are useful in the evaluation of patients with suspected renal arterial and aortic pathology. As an initial evaluation, duplex ultrasound has been shown to be both highly sensitive and specific in identifying renal and aortic pathologies, including both aneurysm formation and arterial stenosis. To ensure the highest diagnostic yield, the patient should ideally be fasting overnight prior to evaluation, as bowel gas can easily obscure the images. Direct measurements of the aorta and evaluation of velocities in both the aorta and renal arteries are obtained. Aneurysms are easily identified and diagnosed by size measurements alone.

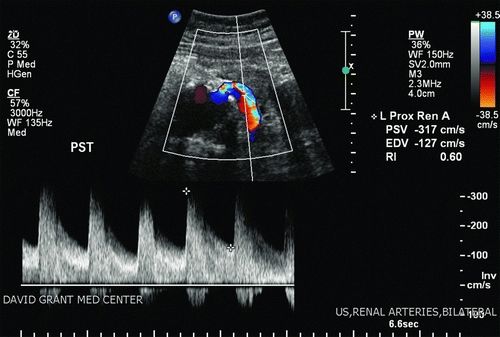

The presence of renal artery stenosis greater than 60% is based upon an elevation in peak systolic velocity (PSV) on spectral Doppler examination above 180 cm/s, along with a velocity ratio of the renal artery as compared to the aorta of greater than 3.5. In circumstances where the aorta and proximal renal arteries are obscured, the aorta is aneurysmal at the renal origins or has occlusive disease present (PSV ≥100 cm/s), useful data can still be obtained by spectral Doppler waveforms more distally in the renal artery. Blunting of the waveform, increased acceleration times above 100 ms, and spectral broadening/poststenotic turbulence patterns suggest more proximal stenosis. Resistive indices should be obtained, particularly in patients with declining renal function. Generally, a resistive index greater than 0.8 suggests renal parenchymal disease as a potential etiology for impaired renal function.

Computed tomographic angiography (CTA) with intravenous iodinated contrast is commonly utilized in the diagnosis of arterial pathology and serves an important role in case planning, particularly for patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) and/or aortoiliac occlusive disease. Today’s available reconstruction software tools make image interrogation much more accurate than in the past. Yet, CTA’s major limitation remains dense arterial wall calcification, producing artifact that degrades image quality and accuracy.

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is also commonly utilized in contemporary practice for aortic and renal artery pathologies. While it does have certain advantages over CTA, particularly the lack of ionizing radiation, it does have several notable limitations. As can be seen in other vascular beds, particularly the carotid arteries, MRA tends to overestimate the true degree of stenosis. It also does not demonstrate calcium within lesions, which makes it less useful for operative planning. Even though MRA does not require intravenous contrast through use of specialized protocols such as time-of-flight, the best images are obtained with adjunctive use of gadolinium. This is unfortunately contraindicated in patients with advanced renal dysfunction, as it can cause a severe and life-threatening condition known as nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, making its widespread use limited for patients with suspected renal artery stenosis.

Additional functional and physiologic tests have been described for assessing renal artery stenosis, such as renin selective venous sampling and captopril scintigraphy. These modalities are not commonly utilized in contemporary practice. They are limited by local expertise in the performance and interpretation of these studies, the demanding preparation required, as well as the lack of evidence regarding their impact on renal function and blood pressure outcomes following intervention.

While conventional angiography remains the gold standard diagnostic modality for renal artery stenosis, it is more commonly performed in conjunction with a planned interventional procedure based on results of another noninvasive test. For suspected aortic aneurysms, digital subtraction angiography (DSA) can commonly underestimate the true size of the aorta, given the presence of mural thrombus/atheroma. As such, it is not used as an initial diagnostic modality. Recent interest in catheter-based tools to interrogate hemodynamic significance of renal artery lesions during arteriography has mounted. Technologies such as intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), pressure gradients by wire or catheter, hyperemic gradient induction, and functional flow reserve calculations have all been evaluated. While no absolute consensus exists, it does appear these adjuncts may provide more sensitive and specific renal lesion description than digital subtraction arteriography alone and is the focus of ongoing clinical study.

The patient underwent a screening aortic and renal artery duplex on the ward. Notably, the maximal infrarenal aortic diameter was 7.5 cm. There was a PSV of 400 on the right and 317 on the left (renal artery-to-aorta ratio of 5.3 and 4.2, respectively). Resistive indices were normal bilaterally (Fig. 1). There was notable blunting of bilateral distal renal artery Doppler waveforms with poststenotic turbulence. Following initiation of nephroprotective measures including administration of N-acetylcysteine and infusion of sodium bicarbonate solution, a CTA of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained. This demonstrated favorable anatomy for endovascular aortic repair and again suggested high-grade bilateral renal artery stenosis.

FIGURE 1 Left renal artery duplex evaluation indicating severe renal artery stenosis with poststenotic turbulence. A normal resistive index does not suggest significant parenchymal disease.