Compartment Syndrome

MARK R. HEMMILA

Presentation

A 31-year-old man with no significant past medical history presents to the emergency department 3 hours following an altercation. He has multiple gunshot wounds in his left anterior thigh from a handgun, and a small amount of blood is emanating from these wounds. On physical examination, he has an obvious left femur deformity with swelling in the region of the wound and associated long bone instability. Examination of bilateral lower extremities reveals a cool, mottled left lower extremity with numbness and weakness in the foot. The right femoral, popliteal, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial pulses are all easily palpable and normal. The left femoral pulse is 2+, and the left popliteal, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial pulses are absent on both palpation and Doppler interrogation.

Differential Diagnosis

Potential injured neurovascular structures in this patient include the superficial femoral artery, popliteal artery, superficial femoral vein, popliteal vein, and sciatic nerve. The neurologic changes can be associated with direct trauma to the peripheral nerves or secondary injury from ischemia. Concern for compartment syndrome should be entertained secondary to potential vascular injury with ischemia and the presence of long bone fractures with associated swelling.

Compartment syndrome develops when tissue expansion in a rigidly confined space generates pressure that exceeds the capillary perfusion pressure of the tissue residing in the closed space.

Noncompliance of the fascial envelope leads to a rapid increase in the compartmental pressure, which may exceed the capillary perfusion pressure. This causes further ischemia, added tissue injury, more edema, and increased pressure—a cycle that eventually results in severe and permanent tissue damage. Traditionally, compartment syndrome has been considered a disease of the fascial compartments that enclose muscle and neurovascular structures within the extremities. However, compartment syndrome can occur in other fascial compartments of the body, such as the abdomen. The development of compartment syndrome is usually an unavoidable process associated with trauma or acute vascular occlusion and ischemia. However, permanent damage to the compartmental contents is preventable and in most circumstances represents a delay in diagnosis or inadequate treatment.

Compartment syndrome should be considered in every patient with an injured extremity or acute vascular compromise. Conditions that are associated with a high incidence of compartment syndrome include fractures, crush injuries, large volume resuscitation, acute arterial compromise, and acute venous occlusion. Less common potential causes of compartment syndrome are a tight dressing or cast, eschar from a circumferential burn, soft tissue swelling from envenomation, and application of military antishock trousers.

The five Ps (pain, paresthesias, paralysis, pulselessness, and pallor) are a common mnemonic for signs and symptoms consistent with compartment syndrome. Pain out of proportion to the severity of injury is a sensitive symptom in an awake patient. Stretching of the muscle group involved often exacerbates the pain caused by excessive pressure in the compartment. The appearance of paresthesias can be early, and sensory abnormalities are indicators of nerve compression and ischemia. Paralysis is typically a late finding due to prolonged nerve compression or irreversible muscle damage. Pulselessness from compartment syndrome alone is a late event and indicates a delay in diagnosis. Often, pulselessness results from acute occlusion of the artery from emboli, thrombus, or trauma and initiates the tissue ischemia leading to compartment syndrome. Early discovery of pulselessness and paralysis, which are typically late findings in the setting of compartment syndrome, should raise the possibility of neurovascular injury. As pressure builds in the compartment, it causes compression of the capillaries, leading to decreased skin perfusion and localized pallor. Physical examination revealing a tense, firm extremity during palpation of the tissue is worrisome and can be easily compared to the contralateral fascial compartment.

Open long bone fractures with extensive soft tissue injury is an unusual setting in which compartment syndrome can occur. A common pitfall is to assume that the open nature of injury provides complete decompression. This rationale is false and can lead to catastrophic results. Initial treatment should be triggered when suspicion arises for compartment syndrome based on clinical findings. Orthopedic casts or tight dressings are removed; escharotomies are performed in burn patients. If the patient’s symptoms do not improve, a decompressive fasciotomy is indicated. In equivocal cases, measurement of the compartment pressure may be helpful. No established benefit has been proven in humans from the administration of pharmacologic agents such as antioxidants or mannitol.

Workup

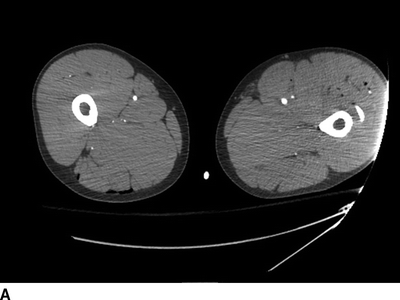

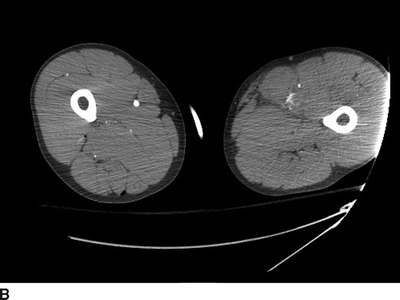

The patient undergoes performance of a pelvic x-ray and plane film examination. To evaluate for vascular injury, a computed tomography angiogram is obtained of the left lower extremity. Findings are a severely comminuted fracture of left proximal femur diaphysis and left medial femoral condyle extending into the distal femoral metadiaphysis with possible extension to the articular surface. Soft tissue changes with adjacent foreign bodies consistent with history of gunshot wound (Fig. 1). There is a high-grade laceration of the left superficial femoral artery with associated pseudoaneurysm and thrombosis (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 1 Computed tomography scan scout film.

FIGURE 2 Selected cuts of CT angiogram through bilateral thighs (A, proximal; B and C, mid; D, distal).

Diagnosis and Treatment

The patient is taken emergently to the operating room where he undergoes rigid sigmoidoscopy to rule out rectal injury. This is followed by left medial thigh exposure of the superficial femoral and popliteal artery, debridement of the damaged arterial tissue, thromboembolectomy of the popliteal and both tibial arteries, and placement of a temporary arterial shunt. Orthopedic surgery stabilizes his femur fracture by placing a spanning external fixator and performs arthroscopic irrigation and debridement of the left knee. Definitive vascular repair is performed by placing a 6-cm segment of saphenous vein graft to replace the damaged artery. It is now 7 hours since his injury and 1 hour since his left lower extremity was revascularized.

This extremity has been ischemic for 6 hours. Arterial circulation has been reestablished, and the patient is currently in the reperfusion period. Concern for compartment syndrome of the left lower leg should be extremely high based on the injury sustained, duration of ischemia, and the preoperative neurologic examination. Three options exist: (1) assume presence of compartment syndrome based on the history of the case and immediately perform four-compartment fasciotomies, (2) measure compartment pressures and proceed with fasciotomy if values greater than 25 to 30 mm Hg are obtained, and (3) observe the patient postoperatively for signs and symptoms of compartment syndrome and return to the operating room for fasciotomy if clinically indicated. You choose option 1 as the safest approach for the patient in this case. Option 3 requires an awake, cooperative patient, with the ability to perform hourly neurovascular examinations. To safely pursue option 3, the patient must have no neurologic deficits preoperatively or postoperatively and must have the ability to return promptly to the operating room should the need for fasciotomy arise.

Surgical Approach

Release of pressure in the compartment is performed by longitudinally incising the fascia in one location per compartment in the affected extremity. In general, all compartments of the involved portion of the extremity should undergo fasciotomy. The calf has 4 compartments, the thigh 2, the foot 10, the arm 3, and the forearm 2. Following release of the compartment, the exposed muscle should be assessed clinically for tissue damage and viability. Does it bulge through the fascial incision? Is it beefy red or dusky, purple, gray, black, or brown? Does the muscle contract when stimulated with the electrocautery? All clearly nonviable tissue should be debrided. Equivocal tissue should be reassessed for viability with serial examinations, and the patient returned to the operating room for debridement if marginal tissue progresses to nonviability.

The standard incisions for a four-compartment lower leg fasciotomy are lateral and medial through the skin of the calf (Table 1). The lateral incision is placed slightly anterior to the fibula and lateral to the anterior tibial crest. This provides access to the anterior and lateral compartments of the lower leg. Creating a short transverse incision through the leg fascia can aid in locating the intramuscular septum between the two compartments. The superficial peroneal nerve lies posterior to this membrane in the lateral compartment. When longitudinally dividing the fascia of the lateral compartment, care must be taken to avoid dividing or injuring this nerve. The medial incision is created 2 cm posterior to the posterior crest of the tibia, which is midway between the anterior and posterior calf borders. The surgeon should avoid injuring the saphenous nerve and vein. Another transverse incision is made to identify the intramuscular septum between the superficial and deep posterior compartments. Using Metzenbaum scissors, longitudinal fasciotomies are performed to open the two posterior compartments. Generous skin incisions should be made and usually run at least 15 to 20 cm in length. If any doubt is present about the adequacy of fasciotomy, the incisions in the skin and fascia should be extended until this uncertainty is eliminated.

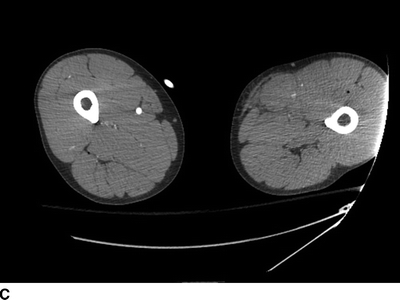

TABLE 1. Key Technical Steps and Potential Pitfalls