On March 11, 2011, a huge tsunami attacked the northeastern coast of Japan after a magnitude 9 earthquake. No reports have investigated the impact of tsunamis on the incidence of cardiovascular disease, especially heart failure (HF). We investigated the number and clinical characteristics of hospitalized patients with acute decompensated HF (ADHF) in the east coast of Iwate hit by the tsunami (tsunami area) for a 12-week period around the disaster. For comparison with previous years, numbers of ADHF were surveyed in the corresponding area in 2009 and 2010. In addition, to elucidate the impact of the tsunami, a similar study was performed in a remote area where the tsunami had minimal effect (control area). After the disaster, the number of patients with ADHF in the tsunami area was significantly increased compared to the predisaster period (relative risk 1.97, 95% confidence interval 1.50 to 2.59). The peak was found 3 to 4 weeks after the disaster. In contrast, in the control area, no significant change in ADHF events was observed (relative risk 1.29, 95% confidence interval 0.94 to 1.78). There was a significant correlation between changes in the number of ADHF admissions and percent tsunami flood area (r = 0.73, p <0.001) or the number of shelter evacuees (r = 0.83, p <0.001). In conclusion, these findings suggest that large and sudden changes in daily life and the trauma associated with a devastating tsunami have a significant impact on the incidence of ADHF.

On March 11, 2011, a massive magnitude 9.0 earthquake occurred off Japan’s Pacific coast and hit the northeast of the country. The earthquake was followed by a devastating tsunami that struck the coastal area and destroyed many coastal communities including the east coast of Iwate (San-riku region). Although large-scale tsunamis have the potential to cause an enormous impact on environmental conditions and mental health in populations living near coastlines, no reports have investigated the impact of tsunamis on the incidence of any cardiovascular disease, specifically acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF). The purpose of our study was to investigate the effects of the tsunami on the onset of ADHF and to determine the associated clinical characteristics within the eastern part of the Iwate prefecture.

Methods

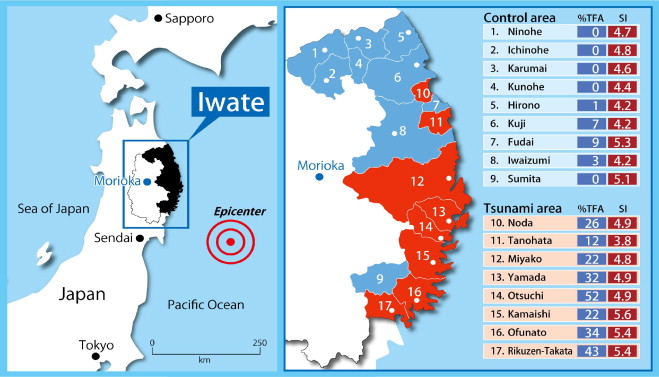

To elucidate the effects of tsunami on health problems, we defined 2 areas ( Figure 1 ) : the coastal area in the southern San-riku region damaged by the huge tsunami (tsunami area) and the northern San-riku region and inland of Iwate where minimal tsunami damage occurred (control area). The definition was based on the percent tsunami flood area per built-up area (%TFA) in each coastal municipality. This ratio represented the degree and extent of damage caused by the tsunami in the residential area of each town. The tsunami-affected area was defined as %TFA >10%. The control area was defined as a percentage <10% or a remote area without a coastline. As shown in Figure 1 , median %TFA in the tsunami area was 29% (range 12 to 52). Seismic intensity in each municipality was determined according to officially published data from the Japan Meteorological Agency. For municipalities where this information was unavailable, data for the nearest town were used as a substitute. Mean values for seismic intensity were 4.6 ± 0.4 in the control area and 5.0 ± 0.6 in the tsunami area ( Figure 1 ). There was no significant difference in seismic intensity between the 2 areas (p = 0.154). The number of evacuees in shelters on April 10, 2011 (1 month after the disaster) in each municipality was determined from officially published data from the Iwate prefecture government. The percentage of evacuees in shelters was significantly larger in the tsunami area than in the control area (26% vs 0.3%, p <0.001). The percentage of elderly subjects (>65 years old) was comparable between the control area and the tsunami area (31% vs 32%).

The control area consisted of 9 municipalities (Ninohe, Ichinohe, Karumai, Kunohe, Hirono, Kuji, Fudai, Iwaizumi, and Sumita) located in the northeast and inland area of the Iwate prefecture ( Figure 1 ). There were 6 public general hospitals in the control area, and 2 of the 6 had a cardiology department (Ninohe and Kuji hospitals). The tsunami area consisted of 8 municipalities (Noda, Tanohata, Miyako, Yamada, Otsuchi, Kamaishi, Ohfunato, and Rikuzen-Takata). There were 6 public general hospitals, with 2 having a cardiology ward (Kamaishi and Ohfunato hospitals). In the 2 areas, patients with ADHF were admitted mostly to the hospitals that had a cardiology department. Other hospitals without full-time cardiologists and local general practitioners did not provide care for patients with ADHF on a regular basis.

The study team including trained research nurses retrospectively checked medical charts and registered all events that might have met the Framingham diagnostic criteria in all hospitals in the tsunami and control areas. Subjects with ADHF were enrolled only if they had been hospitalized and fulfilled the following conditions: (1) were residents of a study district, (2) were ≥20 years old, and (3) were admitted during a 12-week period around the disaster from 4 weeks before (February 11 to March 10, 2011) to 8 weeks after (March 11 to May 5, 2011). Patients were excluded if they had been hospitalized (1) within 4 weeks after onset of acute myocardial infarction or typical apical ballooning (takotsubo) syndrome, (2) with advanced-stage malignant tumor and/or preceding apparent pneumonia, (3) to undergo elective cardiac catheterization, (4) for the introduction of β-blocker therapy, or (5) with end-stage renal failure and no apparent cardiac dysfunction. Patients hospitalized with ADHF for the corresponding periods in 2009 and 2010 were also surveyed to act as a time control. To capture cases transferred from the study area to inland medical centers in Iwate, the survey was extended to 2 teaching hospitals in Morioka including our university hospital and a Red Cross hospital.

To ensure that nearly all appropriate cases had been identified, we reviewed medical charts and/or discharge summaries from admissions to cardiology and internal medicine wards of all general hospitals within the study district. Patients who had been transferred to another hospital were counted on the index admission only. After the disaster, echocardiographic evaluation such as left ventricular ejection fraction assessment was performed in 92% of patients in the control area and 80% patients in the tsunami area.

Approval was obtained from the ethics review board of each participating hospital before commencement of the study.

The primary goal of the present study was to compare numbers of patients with ADHF who were admitted to all hospitals located in the study area during the 8-week period (March 11 to May 5, 2011) in the predisaster (2009 and 2010) and postdisaster (2011) years.

For comparison to predisaster years, the relative risk of ADHF incidence and its 95% confidential interval (CI) were calculated from a 2-by-2 table as follows:

| Events | Nonevents | |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | a | b |

| 2009–2010 | c | d |

The adult population (≥20 years old) of the study areas was assumed by population statistics at October of each year (control area 115,369 in 2009, 111,683 in 2010, 111,475 in 2011; tsunami area 169,742 in 2009, 170,733 in 2010, 160,965 in 2011).

The secondary goal was analysis of demographic and clinical data including outcomes in these patients. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD. Group comparisons before and after the disaster are based on Student’s t test or chi-square test, as appropriate. Comparison for median duration of hospital stay before and after the disaster was made using Mann–Whitney U test. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to examine associations between changes in ADHF numbers before and after the disaster and %TFA or the number of evacuees in shelters. In these analyses, mean values for ADHF admission in the previous 2 years were used for the predisaster data. A significant difference was defined as a p value <0.05.

Results

In the tsunami area during the 8 weeks after the disaster, 97 patients with ADHF were admitted. Compared to the number of the previous 2 years (n = 104), the relative risk of ADHF incidence in the tsunami area was 1.97 (95% CI 1.50 to 2.59). In contrast, in the control area, the number of hospitalized ADHF cases for the corresponding periods were 96 (sum of 2009 and 2010) and 61 (2011). There was no significant increase in ADHF numbers in the control area (relative risk 1.29, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.78).

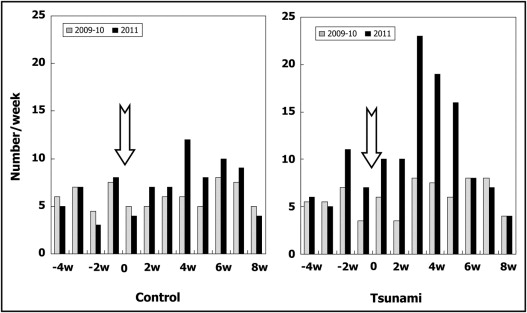

Weekly changes in numbers of hospitalized cases of ADHF before and after the disaster in the 2 areas are shown in Figure 2 . In the tsunami area, the number of hospitalized patients with ADHF was comparable to previous years for the first 2 weeks after the disaster, peaking at 3 to 4 weeks and then decreasing to levels seen in the preceding years. In contrast, in the control area, there were no significant differences in numbers before and after the disaster.

As shown in Figure 3 , changes in the number of hospitalized patients with ADHF in each town before and after the disaster were significantly correlated with %TFA (r = 0.73, p <0.001) or with numbers of evacuees (r = 0.83, p <0.001).

As presented in Table 1 , when the period after the disaster from March 11 to May 5 (8 weeks) was compared to the corresponding periods in 2009 and 2010, no significant change was seen in mean age of patients with ADHF (from 82 ± 11 to 83 ± 9 years in control area, p = 0.55; from 78 ± 12 to 81 ± 11 years in tsunami area, p = 0.09). Similarly, there was no significant change in the percentage of women before and after the disaster (from 64% to 57% in control area, p = 0.40; from 45% to 55% in tsunami area, p = 0.32). New-onset cases before (2009 and 2010) and after (2011) the disaster also remained similar, being 54% and 48% in the control area (p = 0.51) and 57% and 59% in the tsunami area (p = 0.88). Percent cases of ADHF complicated with atrial fibrillation were not significantly different before and after the disaster (59% vs 60% in control area, p = 0.94; 75% vs 65% in tsunami area, p = 0.18). In cases evaluated by echocardiography, the percent of cases in the control area showing preserved left ventricular ejection fraction of >50% was not significantly changed before and after the disaster (38% vs 50%, p = 0.22). However, percent cases in the tsunami area increased significantly from 27% to 45% (p <0.05). Percentage of patients with ADHF transferred from evacuation shelters or temporary housing to hospitals in the study region was 46% in the tsunami area. With respect to drug adherence, 35% of patients declared discontinuation or replacement of vital drugs owing to loss of pills or prescribing information because of the tsunami.