In this prospective, randomized controlled study, we aim to compare the performance outcomes of standard catheters with the radial artery–specific catheter. Over the past decade, transradial cardiac catheterization has gained widespread popularity because of its low complication rates compared with transfemoral access. Operators have the choice of using either standard catheters (used for both transfemoral and transradial approach, with need for separate catheter use for either right or left coronary artery engagement) or a dedicated radial artery catheter, which is specifically designed to engage both coronary arteries through radial artery access. A total of 110 consecutive patients who underwent coronary angiography at our institution from March 2015 to April 2015 were prospectively randomized to either radial artery–specific Tiger catheter (5Fr; Terumo Interventional Systems, Somerset, New Jersey) versus standard Judkins left and right catheters (5Fr R4, L4; Cordis Corporation, Miami, Florida). The end points of the study included fluoroscopy time, dose-area product, contrast volume used, and total procedure time for the coronary angiography. A total of 57 patients (52%) were randomized to radial artery–specific catheter and 53 (48%) to the standard catheter. Tiger catheter was associated with significantly lower fluoroscopy time (184 ± 91 vs 238 ± 131 seconds, p = 0.015), which was statistically significant. Other outcome measures such as dose-area product (2,882.4 ± 1,471.2 vs 3,524.6 ± 2,111.7 Gy·cm 2 , p = 0.07), total contrast volume (48.1 ± 16.1 vs 53.4 ± 18.5 ml, p = 0.114), and total procedure time (337 ± 382 vs 434 ± 137 seconds, p = 0.085) were also lower in single-catheter group, but it did not reach statistical significance. A total of 8 patients (14%) were crossed over from radial-specific catheter arm to standard catheter arm because of substandard image quality and difficulty in coronary engagement. Six patients had to be switched to femoral access (3 in each group) secondary to radial artery spasm. In conclusion, the radial artery–specific catheter was shown to have significantly lower fluoroscopy times but higher failure rates compared with the standard catheters.

The purpose of this study was to compare the performance outcomes of the traditional Judkins left and right catheter with the novel Tiger catheter in patients who underwent coronary angiography through transradial access.

Methods

A total of 110 consecutive patients who underwent coronary angiography at our institution from March 2015 to April 2015 were enrolled in this study. A written informed consent was obtained before the procedure, and block randomization method was used to assign patients to either Judkins catheter or the Tiger catheter. The patients were randomly assigned in blocks of 4 (the blocks were determined with a computer algorithm written in SAS, Cary, North Carolina) to the 2 intervention arms. The operators were notified of the catheter type that the patient was randomized to. All patients who underwent an elective diagnostic coronary angiography were eligible for the study. Exclusion criteria included patients with previous failed attempts at transradial access, a history of coronary artery bypass graft, cardiogenic shock, an abnormal Allen’s test, arteriovenous fistula, or graft. The institutional review board approved the study.

All consented patients had a palpable radial artery pulse and a positive modified Allen’s test to confirm patency of both radial and ulnar arteries before the procedure. The right radial approach was used in all patients. The arm and forearm of the patient were slightly extended, and the wrist was placed in supine position secured next to patient’s hip. After local anesthesia with 0.5% lidocaine, the radial artery was punctured using the Seldinger technique with a 22-gauge needle, and a 6Fr × 16-cm sheath (Terumo Cardiovascular) was introduced over the wire. No sedation was used. To prevent arterial spasm, 300 mg of nicardipine was administered through the sheath followed by 2,000 to 3,000 units of Heparin. On completion of the procedure, the sheath was removed and hemostasis was achieved using “TR Band” hemostatic device (Terumo Cardiovascular) placed over the arteriotomy and inflated with 12 to 13 cm 3 of air.

All procedures were performed by highly skilled and experienced operators (SA, RF, BM, RF, EB, MF, and JS), accompanied by a senior interventional fellow with an experience of >200 transradial coronary angiography. All operators were proficient in using both Judkins and Tiger catheters.

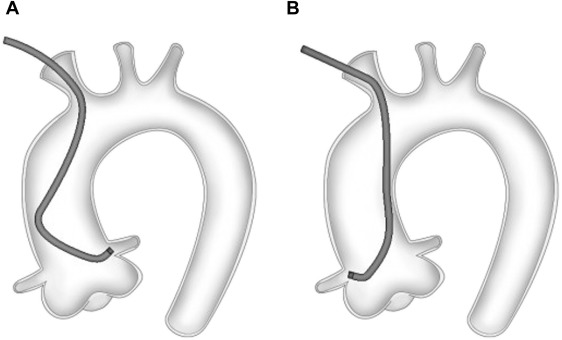

A 30-degree left anterior oblique or anteroposterior projection was used for manipulating the catheters. A standard, fixed-core, 153-cm-long, 3-mm, J-curve 0.035″ guidewire was used for the insertion and exchange of catheters. Automated contrast injectors were used for injecting the contrast material. With the guidewire positioned in the aortic cusp, the catheters were advanced under fluoroscopic guidance. When using a Judkins catheter, the guidewire was pulled back after the catheter was seated in the left coronary sinus, and then the ostium of the left coronary artery was engaged ( Figure 1 ). After successful completion of the left coronary angiography, a 190-cm J exchange wire was used, the Judkins left (JL) catheter was removed, and the Judkins right (JR) catheter was advanced over the wire. Although in our catheterization laboratory, fluoroscopic guidance is generally not used during the catheter exchange, there are a small number of cases where fluoroscopic guidance was used to confirm the position of the wire. The time used to perform this catheter exchange was excluded for study purpose. When the tip of the JR catheter reached the aortic cusp, the guidewire was removed, the RCA was engaged, and right coronary angiography was obtained ( Figure 1 ).

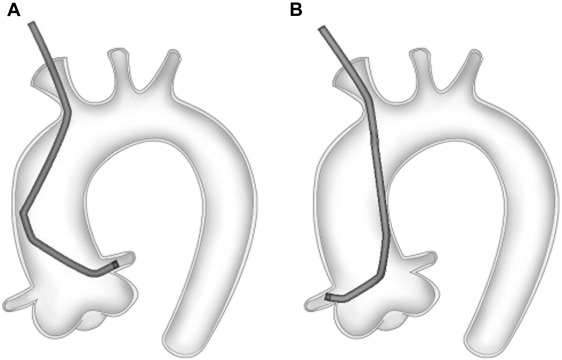

When the Tiger catheter was used, the catheter was advanced over a guidewire into the aortic cusp and the left coronary artery was engaged ( Figure 2 ). After the successful completion of left coronary angiography, the catheter was pulled back from the LCA ostium and then advanced into the right sinus of Valsalva to engage the right coronary artery ostium and right coronary angiography was successfully obtained ( Figure 2 ).

In an event of failure to engage the coronary artery ostium or suboptimal coronary angiography quality using Tiger catheter, the patients were crossed over to Judkins catheter. In an event of failure of Judkins catheter, the catheter selection was left to the discretion of the operator. When the decision was made to do a catheter exchange, access site switch, left heart catheterization, or percutaneous coronary intervention, the study was stopped and the outcomes were measured only up to that point.

The primary end points of the study included (1) fluoroscopy time, defined as the total fluoroscopic time for the coronary angiography, (2) dose-area product (DAP), defined as the absorbed dose multiplied by the area irradiated, expressed in gray square centimeters (Gy cm 2 ), calculated for the total coronary angiography, (3) contrast volume used, defined as the total contrast volume used for the coronary angiography, and (4) total procedure time, defined as the time after which the guidewire was removed and coronary engagement was attempted to the time the coronary angiography was completed.

The secondary end points were the following: (1) procedural success, defined as the successful completion of the angiography without complications; (2) technical success, defined by the completion of the angiography using 1 study catheter without crossover to different catheter type; and (3) access site switch, defined as need to switch access site from radial to femoral to complete the coronary angiography.

We performed unadjusted comparison of catheter performances for patients who underwent coronary angiography using standard catheters versus radial-specific catheters. Student t test was used for comparing continuous variables and the chi-square test for comparing categorical variables. Results are reported as mean ± SD. A p value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS, version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York).

Results

A total of 57 patients (52%) were randomized to radial artery–specific catheter and 53 patients (48%) to standard catheters. No statistically significant differences were found in baseline characteristics between the 2 groups (p <0.05; Table 1 ).The primary end points of the study showed that Tiger catheter have better performance outcomes compared with Judkins catheter ( Figures 3 to 5 , Table 2 ).