Sternal precautions are intended to prevent complications after median sternotomy, but little data exist to support the consensus recommendations. To better characterize the forces on the sternum that can occur during everyday events, we conducted a prospective nonrandomized study of 41 healthy volunteers that evaluated the force exerted during bench press resistance exercise and while sneezing. A balloon-tipped esophageal catheter, inserted through the subject’s nose and advanced into the thoracic cavity, was used to measure the intrathoracic pressure differential during the study activities. After the 1 repetition maximum (1-RM) was assessed, the subject performed the bench press at the following intensities, first with controlled breathing and then with the Valsalva maneuver: 40% of 1-RM (low), 70% of 1-RM (moderate), and 1-RM (high). Next, various nasal irritants were used to induce a sneeze. The forces on the sternum were calculated according to a cylindrical model, and a 2-tailed paired t test was used to compare the mean force exerted during a sneeze with the mean force exerted during each of the 6 bench press exercises. No statistically significant difference was found between the mean force from a sneeze (41.0 kg) and the mean total force exerted during moderate-intensity bench press exercise with breathing (41.4 kg). In conclusion, current guidelines and recommendations limit patient activity after a median sternotomy. Because these patients can repeatedly withstand a sneeze, our study indicates that they can withstand the forces from more strenuous activities than are currently allowed.

Complications such as sternal dehiscence after a median sternotomy can be devastating and may result in prolonged hospitalization, more costly care, and significant mortality. Therefore, providing sternal precautions is a universal part of patient discharge education. Patients are given advice such as “don’t lift more than 5 pounds” (2.3 kg) or “don’t lift more than a gallon of milk” (3.7 kg) ; however, little or no data exist to support these recommendations, which are largely based on expert consensus. To better characterize the forces on the sternum that can occur during everyday events, we conducted a prospective nonrandomized study in healthy subjects that compared the force exerted during a sneeze with that exerted during various bench press resistance exercises.

Methods

Baylor Research Institute’s Institutional Review Board approved the study, and informed consent was obtained from the volunteer subjects who enrolled. Subjects were excluded if they were unable to perform resistance training exercise or could not tolerate the sneeze procurement mechanisms or the insertion of a balloon-tipped esophageal catheter.

The subjects visited the laboratory, which was set up within a cardiac rehabilitation facility, on 2 separate days. On day 1, their age and weight were recorded for descriptive purposes, and their height and gender were recorded for use in calculating the forces on the sternum. Next, the subjects performed a series of bench press exercises with progressively increasing weight to determine the amount they could lift only once (their 1 repetition maximum [1-RM]).

On day 2, an esophageal balloon system was used to measure intrathoracic pressure during the various activities. After administering local anesthesia with lidocaine, a nurse trained in the insertion procedure placed a balloon-tipped esophageal catheter (Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, Connecticut) into the subject’s nostril. The catheter was advanced into the lower third of the esophagus and its placement verified by a negative pressure swing during normal inhalation. The catheter was secured with an adhesive tape across the bridge of the nose. The catheter was then attached to a pressure transducer (MPX 2050DP; Motorola Inc., Phoenix, Arizona) to obtain esophageal pressure as a measurement of intrathoracic pressure. Signals from the pressure transducer were amplified (Grass 7P122 DC; Grass Instruments, Quincy, Massachusetts), converted from analog to digital, and stored for later analysis using the same analog-to-digital system (BIOPAC MP100; Biopac Systems, Santa Barbara, California).

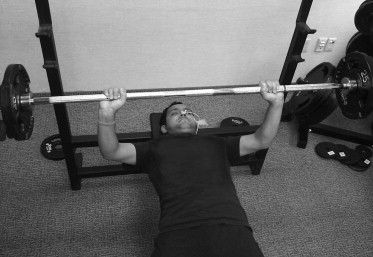

Intrathoracic pressure was measured as the subjects, lying supine on the bench press equipment, performed bench press exercises at 3 intensities: 40% of 1-RM (low), 70% of 1-RM (moderate), and 1-RM (high; see Figure 1 ). At each level of intensity, the subjects lifted weights using the 2 commonly used methods: (1) with controlled breathing (hereafter, B), which is the recommended method, and (2) with the Valsalva maneuver (hereafter, V) or forced exhalation against a closed airway. The subjects rested for 5 minutes between sets; they performed 12 repetitions each for low-B and low-V; 10 repetitions each for moderate-B and moderate-V; and 1 lift each for high-B and high-V.

After completing the bench press exercises, the subjects left the weightlifting station and sat upright in a chair so that intrathoracic pressure could be measured during induced sneezing. Serotonin creatinine sulfate monohydrate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri) was prepared as a 3 mg/ml solution in sterile water without preservatives and was filtered. One spray (300 μg) was delivered into each nostril through a light-resistant metered-dose nasal inhaler and repeated twice as necessary to induce a sneeze; however, this method was not always successful. Other nasal irritants included a medical monofilament (Medical Monofilament Manufacturing, Plymouth, Massachusetts), table pepper, feathers, and even the plucking of a nose hair. After a sneeze was induced, the nurse removed the esophageal catheter.

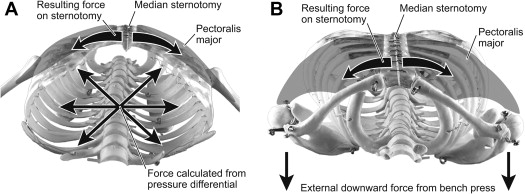

For each of the 6 bench press exercises and the sneeze, the measured distending pressure (the difference between internal and external pressures) for each subject was used to calculate the theoretical force on a median sternotomy closure ( Figure 2 ). Casha et al modeled the chest cavity as cylinder, allowing the calculation of force using the equation T = rlP, where T is the resultant force on the sternotomy closure, r is the internal radius of the chest cavity, l is the length of the thoracic cavity, and P is the distending pressure. In their calculations, Casha et al used fixed values for radius and length that were independent of the subjects’ physical characteristics. For the present study, however, we calculated individual values using data from Bellemare et al, who showed that thoracic dimensions are both gender and height dependent. Specifically, we used their mean values for ribcage cross-sectional area and diaphragm height to calculate the radius and length, respectively, for each subject, assuming the cylindrical model. The cylindrical model can also be used to represent the external force applied by the bench press, and that force was added to the internal force previously calculated ( Figure 2 ).

The null hypotheses were that the mean calculated force exerted during a sneeze is equal to the mean force exerted during each of the 6 bench press exercises. We used a 2-tailed paired t test to verify whether we could reject any of the 6 null hypotheses; a p value <0.05, the designated type I error rate, would legitimize the rejection of the null hypothesis.

Results

Of the 60 subjects initially enrolled, 49 tolerated placement of the esophageal catheter and 41 were induced to sneeze. Data were collected and analyzed from those 41 subjects (19 men [46%] and 22 women [54%]). The mean age was 38 ± 12 years (range 19 to 63), and the mean values for height and weight were 170 ± 8 cm and 82 ± 18 kg, respectively.

The descriptive statistics (means, SDs, minimums, and maximums) for the 7 variables are listed in Table 1 . The mean sneeze force (41.0 kg) was greater than the mean low-B force (23.8 kg) or low-V force (33.4 kg) and comparable with the moderate-B force (41.4 kg).