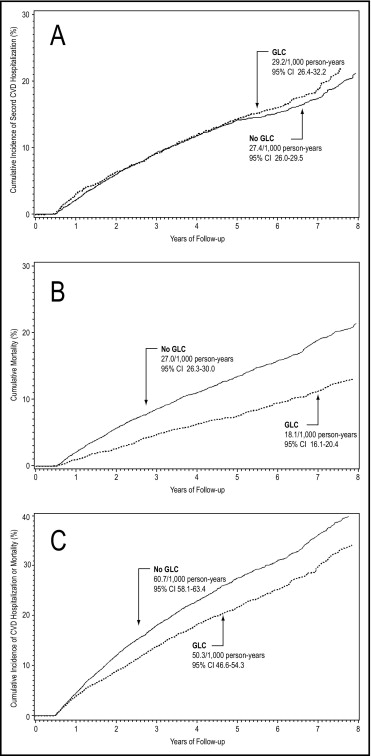

Landmark studies have proved that several therapies reduce cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk; however, the rates of secondary CVD in the context of therapies delivered according to current guidelines are largely unknown. Therefore, we sought to estimate the incidence of secondary CVD hospitalizations and all-cause mortality among patients who did and did not receive guideline-level pharmacotherapy. For the 12,278 patients added to the Kaiser Permanente, Northwest CVD registry in 2000 to 2005, we used the pharmacy records to define guideline-level care (GLC) as at least one dispense of aspirin/antiplatelets, statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, and β blockers within 6 months after registry enrollment. We followed patients until they died, experienced a CVD hospitalization, or June 30, 2008. We compared the age- and gender-adjusted incidence rates per 1,000 person-years of CVD hospitalization, death, and the composite, and estimated the hazard ratios using Cox regression analysis. During a mean follow-up of 45.8 ± 22.8 months, 25% of the study sample experienced the composite outcome. The age- and gender-adjusted incidence per 1,000 person-years of the composite outcome was significantly lower among GLC patients (hazard ratio 50.3, 95% confidence interval [CI] 46.6 to 54.3) versus non-GLC patients (hazard ratio 60.7, 95% CI 58.1 to 63.4). The difference was driven by lower mortality rates (hazard ratio 18.1, 95% CI 16.1 to 20.4 vs hazard ratio 28.1, 95% CI 26.3 to 30.0). The incidence of CVD hospitalizations did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (hazard ratio 29.2, 95% CI 26.4 to 32.2 vs hazard ratio 27.7, 95% CI 26.0 to 29.5). Multivariate adjustment resulted in a marginally significant 8% lower risk of the composite outcome among GLC recipients (hazard ratio 0.92, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.01, p = 0.067). In conclusion, treatment according to current guidelines was significantly associated with reduced mortality but not the risk of secondary hospitalizations.

The American Heart Association / American College of Cardiology has published guidelines for the secondary prevention of CVD. From strong clinical trial evidence, the pharmacologic component of the guidelines has recommended that most patients receive aspirin and/or antiplatelet agents, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in ACE-intolerant patients, statins, and β blockers. Although landmark studies have proved that each of these therapies reduces CVD risk, a substantial number of CVD events occur under optimal clinical trial conditions, even with maximal statin dosing. In clinical practice, however, the use of secondary prevention medications has been proportionately much lower. To our knowledge, the actual rates of secondary CVD in the context of therapy delivered according to the guidelines are largely unknown.

Methods

The study site was Kaiser Permanente, Northwest (KPNW), a 480,000-member group-model health maintenance organization that uses clinical practice guidelines to assist clinicians with patient treatment. We used a retrospective observational cohort study design that capitalized on the comprehensive medical use data maintained by KPNW, including an electronic medical record of all patient encounters, laboratory results that are analyzed by a single regional laboratory using standardized methods, and dispenses from pharmacies located in all clinics. The institutional review board of the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research reviewed and approved the present study.

The KPNW maintains a registry of patients with known CVD, including both cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. The criteria for registry entry include an inpatient diagnosis of myocardial infarction (MI) ( International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification code 410.xx), coronary occlusion without MI (code 411.81), other acute ischemic heart disease (code 411.89), unstable angina (code 411.1), angina pectoris (code 413.x), cerebrovascular disease (codes 433.x, 434.x, 437.x, 438.x); a revascularization procedure (codes 35.96, 36.01, 35.02, 36.05, 36.09, 36.1x, V45.81, V45.82); or a diagnosis on the patient’s problem list of old MI (code 412.x), chronic ischemic heart disease (code 414.x), atherosclerosis (code 440.x), or aortic aneurysm (code 441.x). The patients were automatically added to the registry as of the date of diagnosis (or discharge date). We selected all patients who were added to the CVD registry from 2000 to 2005 (n = 14,705) and defined the registry entry date as the index date. To assess whether patients had received guideline-level care (GLC), we excluded 2,427 patients who had not survived and remained eligible for ≥6 months after their index date, for a final analysis sample of 12,278.

The KPNW guidelines for CVD, electronically available to the clinician at point of contact, are identical to the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines, which recommend all patients with CVD receive, unless contraindicated, aspirin and/or antiplatelet agents, ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and statins. The guidelines also state that patients with MI, acute coronary syndrome, or left ventricular dysfunction should receive β blockers. Using the electronic medical record (where aspirin use is documented) and pharmacy records, we defined GLC as at least one dispense of aspirin/antiplatelets, ACE inhibitors or ARBs, statins, and β blockers, when indicated, within the first 6 months after the index date. We assessed the refill compliance of each component of GLC during the entire observation period using the medicine possession ratio (MPR), dividing the total days of supply of each drug received by the number of observation days. Patients not receiving a specific drug received an MPR value of 0.

We followed patients until they had died, experienced a hospitalization with a primary discharge diagnosis of cardiovascular disease ( International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification codes 410.x to 429.x, 430.x, 431.x, 432.x, 434.x, 435.x, 436.x, 437.1, 402.91) or for a revascularization procedure (codes 35.96, 36.01, 35.02, 36.05, 36.09, 36.1x, 36.29), left the health plan for other reasons, or until June 30, 2008, whichever came first. Deaths were ascertained from the KPNW membership records, but the cause of death was not available.

Patient age (at the index date) and gender were extracted from the KPNW membership records. The body mass index was calculated from the height and weight data in the electronic medical record. Blood pressure, smoking history, the presence of diabetes ( International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification code 250.xx), and a history of depression (codes 296.2x, 296.3x, 300.4, 309.1, 311.x) were also collected from the electronic medical record. We extracted the baseline lipid values from the values recorded in the laboratory database in the year preceding registry entry. We used serum creatinine values to estimate the glomerular filtration rate from the Modification Diet in Renal Disease formula.

We conducted bivariate comparisons of patients who did and did not receive GLC using t tests for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. We calculated and compared the age- and gender-adjusted incidence rates of each outcome per 1,000 person-years using regression for incidence densities based on the first occurrence of the outcome. We then used Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to determine the hazard ratios for GLC, controlling for age, gender, body mass index, blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, estimated glomerular filtration rate, diabetes, previous MI, previous stroke, history of cigarette smoking, and history of depression. All analyses were conducted using Statistical Analysis Systems, version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Table 1 lists the characteristics of the 12,278 study subjects at entry into the CVD registry, stratified by whether they subsequently received all 4 components of GLC in the first 6 months after their index date. As listed in Table 2 , the use of each of the GLC secondary preventive medications was already considerably greater among GLC patients before baseline. Within 6 months of registry entry, the use rates of the GLC medications improved considerably in the entire sample, but they remained well below 100% for non-GLC patients. Nonetheless, most non-GLC patients were receiving ≥2 components of GLC.

| Variable | Total (n = 12,278) | GLC | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 3,283) | No (n = 8,995) | |||

| Age (years) | 66.1 ± 12.5 | 64.0 ± 11.4 | 66.8 ± 12.9 | <0.001 |

| Age ≥65 years | 54% | 46% | 56% | <0.001 |

| Men | 59% | 65% | 57% | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 30.1 ± 6.2 | 31.0 ± 6.2 | 29.8 ± 6.2 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index ≥30 kg/m 2 | 45% | 52% | 42% | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 135 ± 17 | 136 ± 18 | 135 ± 17 | 0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 77 ± 10 | 77 ± 10 | 76 ± 10 | <0.001 |

| Uncontrolled blood pressure ⁎ | 45% | 49% | 43% | <0.001 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dl) | 108 ± 34 | 105 ± 34 | 109 ± 35 | <0.001 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥100 mg/dl | 56% | 52% | 57% | <0.001 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (ml/min) | 77 ± 26 | 79 ± 23 | 77 ± 27 | <0.001 |

| Glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min | 22% | 30% | 23% | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 19% | 30% | 16% | <0.001 |

| Depression | 9% | 9% | 9% | 0.699 |

| Ever smoked | 56% | 59% | 55% | <0.001 |

| Source of identification | <0.001 | |||

| Inpatient diagnosis | 14% | 16% | 13% | |

| Revascularization procedure | 13% | 15% | 12% | |

| Outpatient diagnosis | 73% | 69% | 75% | |

| Identification diagnosis | <0.001 | |||

| Cardiovascular | 86% | 92% | 84% | |

| Cerebrovascular | 14% | 8% | 16% | |

⁎ Defined as blood pressure >130/80 for patients with diabetes and >140/90 for all other patients.

| Variable | Total (n = 12,278) | GLC | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 3,283) | No (n = 8,995) | |||

| Baseline | ||||

| Aspirin/anti-platelet use | 48% | 61% | 43% | <0.0001 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker use | 30% | 58% | 20% | <0.0001 |

| Statin use | 39% | 56% | 32% | <0.0001 |

| β-Blocker use | 48% | 55% | 45% | <0.0001 |

| Mean No. of guideline-level care components | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 2.3 ± 1.5 | 1.4 ± 1.2 | <0.0001 |

| Distribution of guideline-level care components | ||||

| 0 | 27% | 2% | 30% | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 21% | 1% | 24% | |

| 2 | 22% | 16% | 25% | |

| 3 | 20% | 25% | 19% | |

| All 4 | 9% | 28% | 2% | |

| 6 Months after cardiovascular disease identification | ||||

| Aspirin/anti-platelet use | 74% | 100% | 64% | <0.0001 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker use | 44% | 100% | 23% | <0.0001 |

| Statin use | 65% | 100% | 53% | <0.0001 |

| β-Blocker use | 69% | 85% | 63% | <0.0001 |

| Mean No. guideline-level care components | 2.5 ± 1.2 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | <0.0001 |

| Distribution of guideline-level care components | ||||

| 0 | 7% | 0% | 9% | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 14% | 0% | 19% | |

| 2 | 23% | 0% | 32% | |

| 3 | 33% | 15% | 40% | |

| All 4 | 23% | 85% | 0% | |

Figure 1 displays the age- and gender-adjusted cumulative incidence of secondary CVD hospitalizations, all-cause mortality, and the composite outcome, stratified by the receipt of GLC.

Table 3 lists the hazard ratios of patients receiving GLC for the risk of CVD hospitalizations, death, and the composite outcome after multivariate adjustment for age, gender, body mass index of ≥30 kg/m 2 , uncontrolled blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol >100 mg/dl, estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min, diabetes, previous MI, previous stroke, cigarette smoking, and a history of depression. Table 4 lists the results of the Cox regression analyses of compliance as defined by an MPR of ≥80% with each component of GLC in place of the dichotomous GLC variable.

| Variable | Any CVD Hospitalization | All-Cause Mortality | Composite ⁎ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Did not receive guideline-level care | Referent | — | — | Referent | — | — | Referent | — | — |

| Received guideline-level care | 0.97 | 0.85–1.10 | 0.617 | 0.84 | 0.73–0.98 | 0.022 | 0.92 | 0.83–1.01 | 0.067 |

| Age ≥65 years | 1.23 | 1.09–1.34 | <0.001 | 3.21 | 2.74–3.76 | <0.001 | 1.82 | 1.66–2.00 | <0.001 |

| Male gender | 1.10 | 0.98–1.25 | 0.117 | 1.05 | 0.92–1.20 | 0.486 | 1.08 | 0.99–1.18 | 0.091 |

| Body mass index ≥30 kg/m 2 | 1.01 | 0.90–1.14 | 0.891 | 0.70 | 0.62–0.80 | <0.001 | 0.86 | 0.79–0.94 | 0.001 |

| Uncontrolled blood pressure † | 1.26 | 1.11–1.42 | <0.001 | 1.03 | 0.91–1.18 | 0.624 | 1.16 | 1.06–1.26 | 0.001 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥100 mg/dl | 1.01 | 0.90–1.14 | 0.812 | 0.78 | 0.69–0.89 | <0.001 | 0.90 | 0.83–0.98 | 0.016 |

| Glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min | 1.67 | 1.47–1.91 | <0.001 | 1.75 | 1.53–2.00 | <0.001 | 1.74 | 1.58–1.91 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.46 | 1.27–1.67 | <0.001 | 1.34 | 1.15–1.56 | <0.001 | 1.43 | 1.29–1.58 | <0.001 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 1.45 | 1.26–1.66 | <0.001 | 1.11 | 0.95–1.30 | 0.192 | 1.31 | 1.18–1.45 | <0.001 |

| Previous stroke | 0.51 | 0.34–0.74 | <0.001 | 1.25 | 0.96–1.63 | 0.096 | 0.84 | 0.68–1.04 | 0.115 |

| Previous revascularization | 1.25 | 1.07–1.46 | 0.005 | 0.81 | 0.67–0.97 | 0.024 | 1.04 | 1.02–1.17 | 0.506 |

| Ever smoked | 1.09 | 0.96–1.23 | 0.171 | 1.33 | 1.17–1.53 | <0.001 | 1.20 | 1.09–1.31 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 1.42 | 1.24–1.62 | <0.001 | 1.41 | 1.21–1.64 | <0.001 | 1.43 | 1.29–1.58 | <0.001 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree