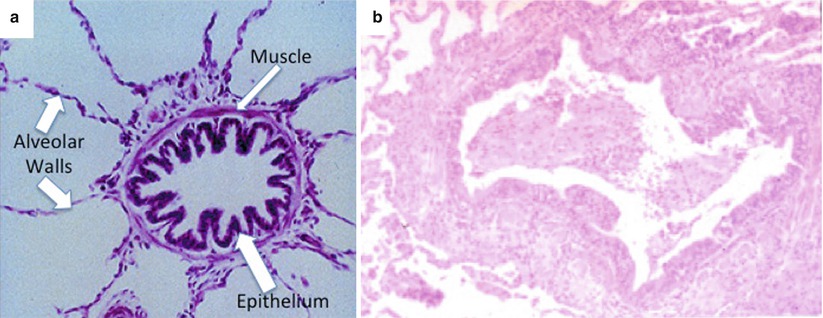

Fig. 3.1

Junctional area between the purely conductive airways and the respiratory portion of the lung. The terminal (nonrespiratory) bronchiole has a continuous cuboidal epithelium, whereas alveoli open off the respiratory bronchiole (Courtesy of Marco Chilosi, MD, Dipartimento di Patologia, Università di Verona)

There may be extensive damage to the small airways before the patient becomes symptomatic or develops detectable abnormalities on lung function testing. Most cases have an insidious onset characterized by cough or dyspnea. Initially, patients are assumed to have more common problems, such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

The epidemiology of bronchiolitis is poorly understood. Bronchiolitis in infants and children is recognized worldwide and often is associated with outbreaks of infection (especially, respiratory syncytial virus) [1]. Adult bronchiolitis is rare and has not been well studied. Many cases are associated with accidents that result in inhalation injuries.

This chapter reviews the clinical, radiographic, and histopathologic findings of the bronchiolar syndromes in adults and is orientated toward practical management. More exhaustive reviews can been found elsewhere [2, 3].

Classification

Bronchiolitis is often confusing because the term describes both a clinical syndrome and a constellation of histopathologic abnormalities that may occur in a variety of disorders. Thus, two classification schemes appear useful in defining cases of bronchiolitis: (1) a clinical classification based on the etiology (Table. 3.1); (2) a histopathologic classification, which includes two major morphologic types (proliferative bronchiolitis and constrictive bronchiolitis) [2].

Table 3.1

Clinical syndromes associated with histologic bronchiolitis

Inhalation injury | Selected examples | |

|---|---|---|

Toxic fumes or Irritant gases | Fire smoke | |

Nitrogen dioxide (e.g., silo gas, chemical, electric arc or acetylene gas welding, contamination of anesthetic gases) | ||

Sulfur dioxide (e.g., burning of sulfur-containing fossil fuels, fungicides, refrigerants) | ||

Ammonia (e.g., fertilizer and explosives, production, refrigeration) | ||

Chlorine (e.g., bleaching, disinfectant and plastic making) | ||

Phosgene (e.g., chemical industry, dye and insecticide manufacturing) | ||

Ozone (e.g., arc welding and air, sewage and water treatment) | ||

Cadmium oxide (e.g., smelting, alloying, welding) | ||

Methyl sulfate | ||

Hydrogen sulfide | ||

Hydrogen fluoride | ||

Other agents (e.g., chloropicrin, trichlorethylene, hydrous magnesium silicate, stearate of zinc powder) | ||

Organic dusts | ||

Mineral dusts | ||

Volatile flavoring agents | ||

Postinfectious | Respiratory syncytial virus | |

Parainfluenza (types 1, 2, and 3) | ||

Adenovirus (types 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, and 21) | ||

Mycoplasma pneumoniae | ||

Drug-induced reactions | Penicillamine | |

Gold | ||

Amiodarone | ||

Busulfan | ||

Free-base cocaine use | ||

Sulfasalazine | ||

Bleomycin | ||

Sauropus androgynus | ||

Paraquat poisoning | ||

Nitrofurantoin | ||

Idiopathic | ||

No associated diseases | Cryptogenic bronchiolitis | |

Respiratory bronchiolitis (cigarette smoke) | ||

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia | ||

Diffuse panbronchiolitis | ||

Associated with other diseases | Associated with organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation | |

Associated with connective tissue disease | ||

Aspiration pneumonitis | ||

Ulcerative colitis | ||

Primary biliary cirrhosis | ||

Vasculitis | ||

Paraneoplastic pemphigus |

Constrictive Bronchiolitis

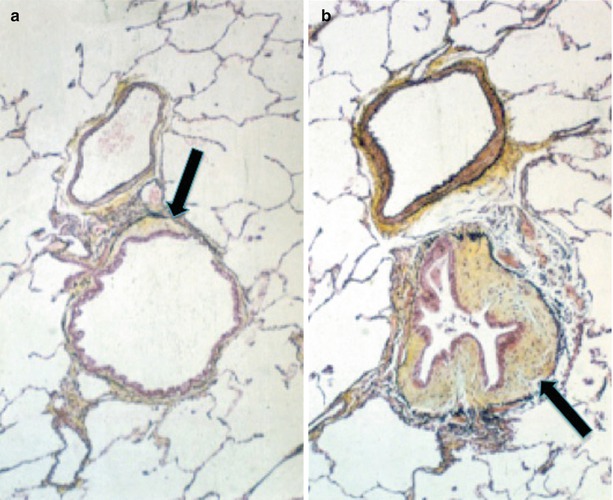

Constrictive bronchiolitis is rare and is characterized by alterations in the walls of membranous and respiratory bronchioles that cause concentric narrowing or complete obliteration of the airway lumen (Fig. 3.2). Often these lesions occur without extensive changes in alveolar ducts or alveolar walls. The histopathologic changes range from subtle cellular infiltrates around the small airways to bronchiolectasia with mucus stasis, distortion, and fibrosis or total obliteration of the bronchioles. Patients with constrictive bronchiolitis often experience progressive obstructive lung disease, e.g., following inhalational injury. The chest imaging studies may be normal. It is useful to further divide constrictive bronchiolitis into five main groups: (1) cellular bronchiolitis, (2) follicular bronchiolitis, (3) diffuse panbronchiolitis, (4) respiratory (smoker’s) bronchiolitis, and (5) cryptogenic constrictive bronchiolitis.

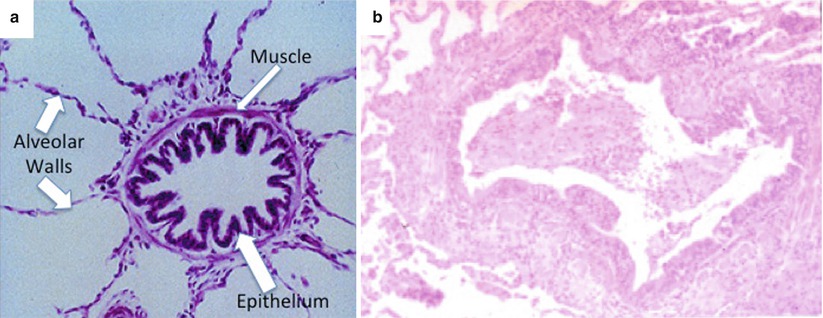

Fig. 3.2

(a) Photomicrograph of normal small airway. (b) Constrictive bronchiolitis. Photomicrograph of lung biopsy specimen shows bronchial smooth muscle hyperplasia, thickening and mild scarring of the bronchiolar wall, and scarring of the adjacent alveoli

Cellular Bronchiolitis

Cellular bronchiolitis is a descriptive histologic term that refers to inflammatory infiltrates that involve the lumen, the walls of bronchioles, or both [2]. The inflammation may be acute, chronic, or both.

Follicular Bronchiolitis

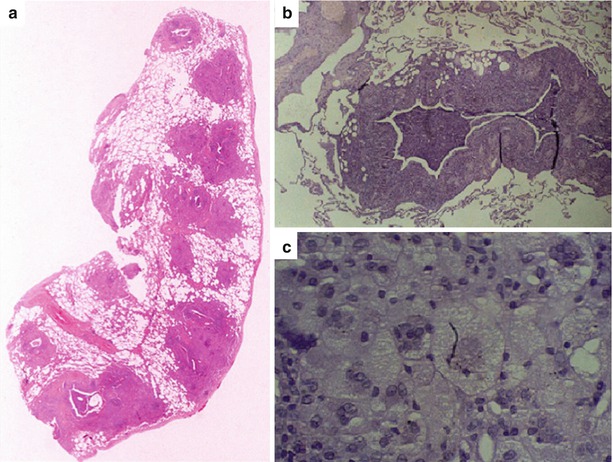

Follicular bronchiolitis is a distinctive subset of cellular bronchiolitis characterized by the dramatic proliferation of lymphoid follicles with germinal centers along the airways and an infiltration of the epithelium by lymphocytes (lymphoid hyperplasia of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue [BALT]) (Fig. 3.3) [4]. Most cases occur in patients with connective tissue disease (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren’s syndrome) [5]. Other associations include immunodeficiency syndromes, familial lung disorders, chronic infection, and a heterogeneous group of patients with a hypersensitivity-type reaction.

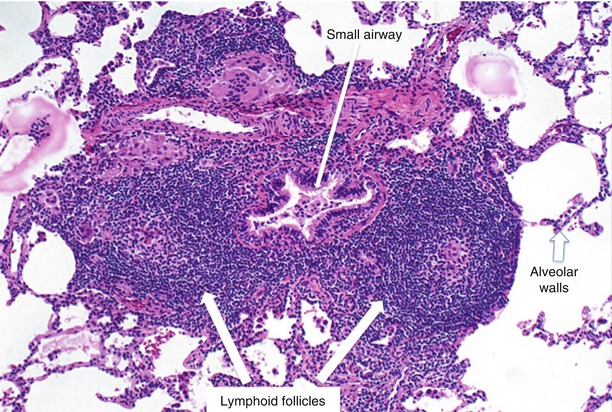

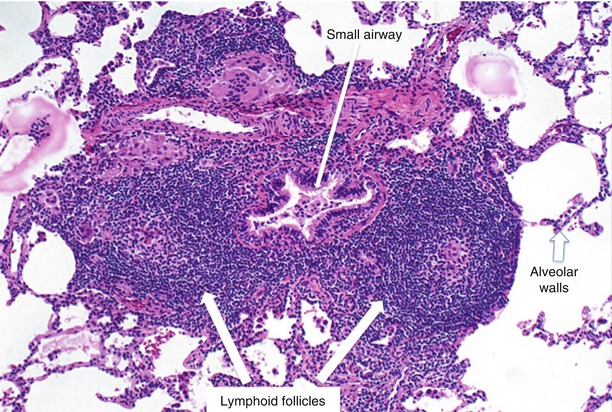

Fig. 3.3

Follicular bronchiolitis. Prominent lymphoid follicles adjacent to and impinging on the distal airway (Courtesy of Jeffrey L Myers, MD, Department of Pathology University of Michigan)

Respiratory Bronchiolitis

Respiratory bronchiolitis is characterized by a cellular reaction in and around respiratory bronchioles. There is mild inflammation of the walls of the respiratory bronchioles, which extends to involve the adjacent alveoli [6]. Slight fibrosis may be present. This lesion is common in smokers and is often associated with a prominent increase in pigmented macrophages in the airway lumina and alveolar spaces.

Airway-Centered Interstitial Fibrosis

Airway-centered interstitial fibrosis (ACIF), also called idiopathic bronchiolocentric interstitial pneumonia and chronic bronchiolitis with fibrosis, is characterized by centrilobular and bronchiolocentric inflammatory infiltrate with peribronchiolar fibrosis and an absence of granulomas [7]. The typical patient is a middle-aged woman (40–50 years old) with a chronic nonproductive cough. Many cases are thought to be characteristic of hypersensitivity pneumonitis on clinical grounds, although no specific antigen has been identified [8]. Unlike hypersensitivity pneumonitis, the percentage of lymphocytes on bronchoalveolar lavage is less than 40 % [7]. Many of the reported patients have a history of smoking, raising concerns that cigarette smoking may be a contributor to airway injury. Chronic silent microaspiration and toxic or hypersensitivity reactions may contribute to the development of this pattern of injury in some patients.

Diffuse Panbronchiolitis

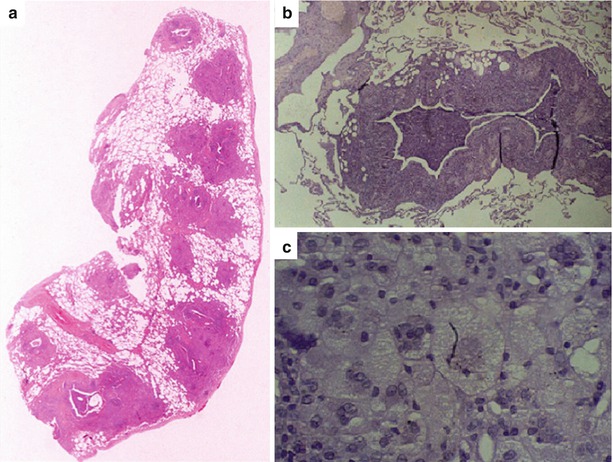

Diffuse panbronchiolitis is an inflammatory process characterized by mononuclear cell inflammation of the respiratory bronchioles and the presence of foamy macrophages in the bronchiolar lumina and adjacent alveoli (Fig. 3.4). These findings often produce nodular lesions [6]. This distinctive form of small airways disease is relatively common in Japan, China, and Korea; it is rare in other parts of the world [9].

Fig. 3.4

(a) Diffuse panbronchiolitis. Scattered nodules are seen at low power. The primary lesion is an inflammatory process of the respiratory bronchioles with marked associated foam cell accumulation (Courtesy of Jeffrey L Myers, MD, Department of Pathology University of Michigan). (b) Inflammatory process in the respiratory bronchioles characterized by mononuclear cell inflammation in the wall. (c) Numerous foamy macrophages are present in the bronchiolar lumina (and adjacent alveoli)

Proliferative Bronchiolitis

Proliferative bronchiolitis is characterized by an organizing intraluminal exudate and is extensive and prominent in organizing pneumonia [10]. The intraluminal fibrotic buds (Masson bodies) are seen in respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveoli. Proliferative bronchiolitis is most frequently associated with diffuse alveolar opacities on chest radiograph and CT scan. A restrictive defect is found on pulmonary function testing.

Diagnosis

Patients, who present with the chronic, insidious onset of cough and dyspnea, especially when the symptoms and signs do not follow a typical pattern, should raise the consideration of bronchiolitis

Clinical Vignette

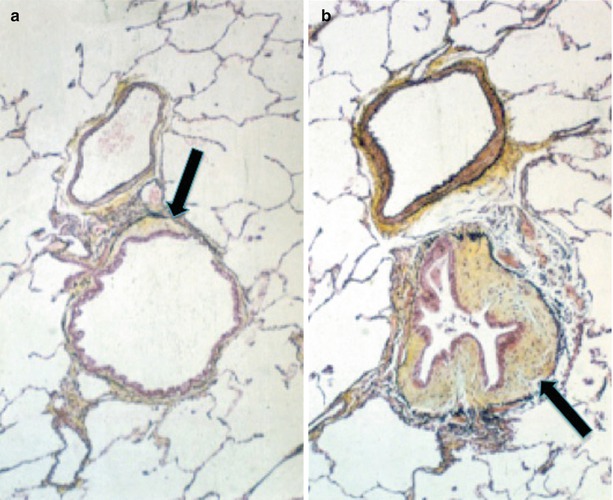

A 42-year-old female never smoker presented with a 12-week history of dyspnea with exertion and a nonproductive cough. She is a secondary school science teacher and an avid runner. She first experienced a nonproductive cough with chest tightness about 15 weeks ago following accidental exposure to a sulfur-based chemical that overheated giving off fumes. She has had progressive worsening of her dyspnea such that she is now not able to run. She has no chest pain, tightness, or heaviness. She is afebrile. Her respiratory rate is 16 breaths/minute, and pulse oximetry shows 96 % saturation on room air. Pulmonary examination shows slight expiratory wheezing and occasional bibasilar rhonchi that clear with coughing. Results of cardiac examination are normal, and no ankle edema is present. Lung function testing revealed moderate airflow obstruction with moderate overdistension. The diffusing capacity was slightly reduced. A chest x-ray showed findings suggestive of hyperinflation. Inspiratory HRCT demonstrated mild bronchiolar dilatation. Expiratory HRCT showed multifocal lobular air trapping in several lobes of her lung. A surgical lung biopsy was performed and showed marked concentric narrowing of the bronchiolar lumen. Step-sectioning of the tissue specimen confirmed the presence of complete obliteration of the bronchiolar lumen due to fibrosis (Fig. 3.5). Following treatment with bronchodilators and oral prednisone, her lung function stabilized with persistent reduction in her exercise capacity.

Fig. 3.5

(a) Slightly dilated bronchiole with minimal fibrosis (arrow) and normal intervening lung (Pentachrome stain; ×156 original magnification). (b) Severe concentric narrowing of the bronchiolar lumen due to fibrosis (arrow) (Pentachrome stain; ×156 original magnification) (Adapted from: King [2])

The differential diagnosis includes severe asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and sarcoidosis. A multidisciplinary approach that considers the clinical setting and radiographic pattern is often helpful [3]. When bronchiolitis is suspected, the most helpful tests are chest imaging, usually a high resolution CT (HRCT) scan, and pulmonary function testing (see Box 3.1).

Box 3.1

Diagnostic Criteria

A.

Bronchiolitis in adults should be diagnosed based on history, physical examination, chest imaging and lung function studies.

The wide range of clinical symptoms and severity can make diagnosis challenging. Useful clinical features consistent with the diagnosis include:

Preceding upper respiratory symptoms, including rhinorrhea and fever

Signs/symptoms of respiratory distress: cough, dyspnea, tachypnea, wheezing, inspiratory crackles and a midinspiratory squeak.

B.

When bronchiolitis is suspected, the most helpful tests are chest imaging, usually a high resolution CT (HRCT) scan, and pulmonary function testing. Viral testing is not routinely recommended.

Chest Imaging studies

Chest x-ray is obtained most commonly to rule-out bacterial pneumonia and to assess disease severity. The chest radiograph is of limited usefulness in the diagnosis and note may be normal or may show varying combinations and degrees of any of the following: hyperinflation, peripheral attenuation of the vascular markings, and nodular or reticular opacities.

High resolution chest CT scans are most useful in identifying findings consistent with bronchiolitis.

Constrictive bronchiolitis: Inspiratory CT scans show: presence of centrilobular thickening, bronchial wall thickening, bronchiolar dilatation, the tree-in-bud pattern, and the mosaic perfusion pattern. Expiratory CT scans may show air trapping (the principal finding on CT, and its severity correlates with lung function).

Proliferative bronchiolitis and organizing pneumonia: The predominant CT findings are bilateral areas of consolidation.

Pulmonary function testing:

Constrictive bronchiolitis: normal or show obstructive changes with air trapping.

Proliferative bronchiolitis: a restrictive pattern is the common.

Diffusing capacity is usually reduced in both types

Resting hypoxemia is frequently present in both patterns.

C.

Lung biopsy–Open or thoracoscopic lung biopsy is commonly required to make a definitive diagnosis.

Chest Imaging Studies

The chest radiograph is of limited usefulness in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with bronchiolitis–may be normal or may show varying combinations and degrees of any of the following: hyperinflation, peripheral attenuation of the vascular markings, and nodular or reticular opacities [11].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree