CHAPTER 25 Chest Wall Tumors

Tumors of the chest wall encompass a variety of bone and soft tissue disorders.1–3 Primary and metastatic neoplasms of both the bony skeleton and the soft tissues as well as primary neoplasms that invade the thorax from adjacent structures, such as the breast, lung, pleura, and mediastinum, are included; benign, nonmalignant conditions of the chest wall, such as infections, cysts, and fibromatosis, are also included (Box 25-1). Almost all of these tumors have been irradiated as the treatment of choice or have been irradiated in combination with chest wall resection.4 It is also not uncommon to have patients present with a postradiation necrotic chest wall neoplasm. The thoracic surgeon is frequently asked to establish a diagnosis for most of these patients, to treat some for cure, and to manage a few for necrotic, foul-smelling chest wall ulcers. All of these entities represent a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. In many patients, surgical extirpation is often the only remaining method of treatment, and this may be compromised by an incorrect diagnosis or an inability to reconstruct large chest wall defects. From a practical standpoint, however, chest wall resection is most frequently used to treat primary chest wall neoplasms.1–35

Because primary chest wall neoplasms are uncommon, relatively few series historically have been reported. Moreover, most early reports included only patients with bone tumors.6–8 When bone tumors are combined with primary soft tissue tumors, however, the soft tissues become a major source of chest wall neoplasms and today account for nearly half of all tumors.

The incidence of malignancy in primary chest wall neoplasms varies and ranges from 50% to 80%. The higher malignancy rates occur in soft tissue tumors. Consequently, when bone and soft tissue tumors are combined, malignant fibrous histiocytomas (fibrosarcomas), chondrosarcomas, and rhabdomyosarcomas are the most common primary malignant neoplasms, and cartilaginous tumors (osteochondroma and chondroma) and desmoid tumors are the most common primary benign tumors.2,5

The type and incidence of chest wall tumors in the pediatric population are somewhat difficult to determine; primitive neuroectodermal tumors, Ewing’s rhabdomyosarcoma, and neuroblastoma dominate the malignant cell types, and chondroma, hamartomas, and desmoid tumors are the frequent types of benign tumors. Chest wall masses are more likely to be malignant in children.9,10

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

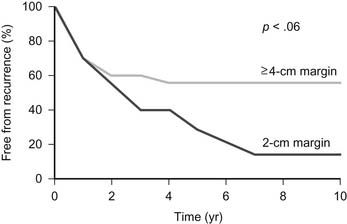

Wide resection of a primary malignant chest wall neoplasm is now recognized as being essential to successful management. However, the extent of resection should not be compromised because of an inability to close large chest wall defects.1–35 Opinions differ with regard to what constitutes wide resection. In a report from the Mayo Clinic that analyzed the effect of the extent of resection on long-term survival in patients with primary malignant chest wall neoplasm,11 56% of patients with a margin of resection of 4.0 cm or more remained free from cancer at 5 years compared with only 29% of patients with a margin of 2.0 cm (Fig. 25-1). For many surgeons, a resection margin of 2.0 cm is considered to be adequate. Although this margin may be adequate for chest wall metastases and benign tumors, a 2.0-cm margin for resection is inadequate for malignant neoplasms. Moreover, more aggressive malignant tumors, such as osteogenic sarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma, have the potential to spread within the marrow cavity or along tissue planes such as the periosteum or parietal pleura. Consequently, all primary malignant neoplasms that are initially diagnosed by excisional biopsy should be resected further to include at least a 4.0-cm margin of normal tissue on all sides. High-grade malignant neoplasms should also have the entire involved bone resected. For neoplasms of the rib, this includes removal of the entire involved rib, removal of the corresponding anterior costal arch if the tumor is located anteriorly, and partial resection of several ribs above and below the neoplasm. For tumors of the sternum and manubrium, resection of the entire involved bone and corresponding costal arches bilaterally is indicated.12 Any attached structures, such as lung, thymus, pericardium, or chest wall muscles, should also be excised. Radiofrequency thermoablation has been described for treatment of a mesenchymal hamartoma of the chest wall in an infant, but its efficacy is unknown.13

Chest Wall Reconstruction

Indications for chest wall resection include primary or metastatic chest wall neoplasms, tumors contiguous from breast or lung, radiation necrosis, congenital defects, and trauma or infectious processes from osteomyelitis or median sternotomy or lateral thoracotomy wounds.14,15 Improvements in preoperative imaging, intraoperative anesthetic management, techniques available for reconstruction, and postoperative care allow almost any pathologic process to be successfully managed by chest wall resection and reconstruction. The tenets of chest wall resection and reconstruction are (1) to remove all devitalized tissue; (2) to restore rigidity to the chest wall if the defect is large, to prevent a flail chest; and (3) to cover with healthy soft tissue to seal the pleural space; to protect underlying organs, and to prevent infection. Because successful management of chest wall lesions often requires input from multiple different specialties, these types of problems are best cared for by a team of physicians including plastic surgeons, pulmonologists, and anesthesiologists as well as the thoracic surgeon.

History

Holden reported the first successful partial sternectomy in 1878, and in 1898, Parham reported resection of the chest wall in continuity with a pulmonary tumor.16 Reconstruction was particularly difficult in these early efforts because of the problems involved in sealing the pleural cavity. With the advent of endotracheal intubation, the difficulties of pneumothorax during chest wall resection were mitigated. Closed-chest drainage, positive-pressure ventilation, and antibiotics further enhanced the success rate of chest wall resection and reconstruction. The 1940s and the war injuries seen in World War II advanced the management of an infected pleural space and ventilation mechanics and brought advances in soft tissue coverage. Watson and James17 described the use of fascia lata grafts to close chest wall defects. The use of rib grafts to reinforce the anterior chest wall after sternectomy was discussed by Bisgard and Swenson.18 The advent of musculocutaneous flaps to cover defects in the chest wall is a major advance in the reconstruction of chest wall defects. The latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap was initially described by Tansini19 in 1906 for coverage of the chest wall after a radical mastectomy. The musculocutaneous flap was again described in the late 1930s and by Campbell in 1950 but, for unknown reasons, was not noticed until 20 years later. The idea of a musculocutaneous flap was then repopularized by Blades and Paul,20 Converse and associates,21 and Myre and Kirklin.22 In the field of thoracic surgery, Jurkiewicz expanded the idea of using muscle flaps to reconstruct the chest wall. Through him and the residents he trained, these techniques are now commonly in use.

There have recently been numerous reports of the use of chest wall musculature to reconstruct the chest wall.23,24 Almost all the thoracic muscles, including the latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major and minor, serratus anterior, rectus abdominis, and external obliques, are now used. Tissue expanders have been added to facilitate transfer of the muscle, and free microvascular transfer has been described to cover chest wall defects. Currently, it is almost always possible to cover aggressive resections with autologous tissue by modern techniques.

For stabilization of the resected bony chest wall, either autologous tissue or synthetic materials have been described. The use of transposed ribs or diced cartilage is of historic interest and is rare today. Fascia lata for reconstruction of chest wall deformities was first described in 1947 by Watson and James.17 Donor cryopreserved rib allografts have been described.25 Synthetic materials are the most commonly used objects today. Marlex, as a material to reconstruct the chest wall, was first described in 1960 by Graham and colleagues.26 Similar meshes were developed with Prolene and Vicryl. More recently, Gore-Tex patches have been constructed for this purpose.

Indications

Reasons for resection of the chest wall vary among different series. The four main reasons are shown in Box 25-2. In a large series by Arnold and Pairolero,27 chest wall tumor was the indication in 275 patients, infected median sternotomy in 142, radiation necrosis in 119, and a combination of these reasons in the remaining 121 patients (Table 25-1). In Cohen’s series of 113 patients, the indications for resection were infection (mostly infected median sternotomies) in 76, radiation necrosis in 23, tumor in 12, and trauma in 2 patients.28 Finally, in another large series by Mansour and coworkers,14 the indications were malignancy in 171, infection in 31, radiation necrosis in 29, and other reasons in 29 patients. The actual distribution is largely determined by the practice patterns of each reporting physician.