Chest Wall Resections

John R. Frederick

John C. Kucharczuk

INTRODUCTION

Indications for chest wall resection are broad and varied. They include resection of both primary and secondary chest wall lesions. Primary chest wall lesions are those that arise within the normal constituents of the chest wall, including skin, connective tissue, muscle, bone, and cartilage. Whether benign or malignant, primary chest wall lesions are relatively uncommon, and resection is often warranted for diagnosis and treatment. Secondary chest wall masses are caused by invasion from a process originating in contiguous organs such as the lung or breast. Lung cancer with chest wall invasion is the most common indication for chest wall resection. In these cases, chest wall resection is performed in stage-appropriate candidates as part of an en bloc resection for attempt at cure.

There are three basic tenets of chest wall resection: (1) resection of all diseases with wide margins, (2) provision of healthy soft tissue coverage, and (3) preservation of respiratory mechanics. The intent of this chapter is to review the indication and techniques of chest wall resection with reconstruction from the simple to the complex. The discussion focuses on the proper selection of reconstructive techniques from “off the shelf” synthetic material to complex soft tissue transfers.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNINGPatients being considered for chest wall resection undergo a complete medical evaluation. Special attention is focused on any past medical or surgical history that will affect the approach for resection and the choices for reconstruction. These factors include previous chest procedures, a history of radiation, evidence of active infection, and immunosuppression. All patients have radiographic imaging, including a chest radiograph and computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest. For patients with a primary chest wall lesion, magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful in delineating the local extent of disease, but as a general rule it cannot distinguish between benign and malignant masses. Patients with underlying lung cancer and contiguous chest wall invasion undergo a complete extent of disease workup to rule out metastatic disease, and if negative, they are considered for resection. If partial vertebral body resection is entertained or there is concern regarding involvement at the level of the neural foramen, preoperative neurosurgical consultation is obtained. Similarly, the need for transfer of large volumes of soft tissue for coverage or unfamiliarity with the available techniques for complex tissue transfer should prompt consultation with an experienced reconstructive surgeon. A tissue diagnosis should be obtained in most cases to differentiate between benign and malignant tumors and to identify malignant neoplasms that may be amenable to medical therapy. This consists of fine needle aspiration, core needle biopsy, or incisional biopsy of lesions larger than 5 cm. Lesions smaller than 5 cm are usually suitable for excisional biopsy.

OPERATIVE PLANNING: OPTIMIZING THE APPROACH

In selecting the appropriate incision, it is imperative that the surgeon be thoughtful, flexible, and experienced. The optimal surgical approach allows for the assessment of the extent of disease without violation of the lesion. Lateral chest wall lesions are generally approached through posterolateral incisions. If there is a planned need for soft tissue transfer, the latissimus dorsi and serratus anterior muscles are mobilized but not divided before entering the pleural cavity. If there is no need for tissue transfer, we generally divide the latissimus dorsi muscle but spare the serratus anterior in case it should be needed in the future. The pleural cavity is entered either at an interspace below the lesion or at a site anterior to the lesion. The lesion is palpated to determine the extent of resection required. Primary chest wall lesions rarely invade the lung, and pulmonary resection is usually not required. In cases of lung cancer with contiguous chest wall involvement, the chest wall resection is performed as shown in an en bloc manner. Attempts to develop an extrapleural plane or strip the tumor off the chest wall should be avoided because this risks violation of the tumor with contamination of the pleural cavity and consequently a high likelihood of recurrence. Once the chest wall resection is complete, the chest wall bloc remains attached to the underlying pulmonary parenchyma while the pulmonary resection is performed. No attempt is made to separate the chest wall bloc from the underlying lung.

Lesions involving the apex of the chest can be approached via the traditional Shaw-Paulson technique. This approach uses a long posterolateral incision carried up to the C7 vertebral body, elevation of the scapula off the chest wall after division of the trapezius and the rhomboids, and chest wall resection from a posterior approach. Recently, it has been recognized that these apical lesions may be more effectively managed through the anterior cervicothoracic approach described by Dartevelle and subsequently modified by others. Anterior chest wall lesions are often best approached with the patient supine and an anterior incision made over the location of the lesion.

Regardless of the surgical approach chosen, the basic tenets of chest wall resection must be fulfilled. These include a wide margin of excision, en bloc anatomic resection with the attached lung parenchyma, and appropriate reconstruction of the chest wall defect when required.

TECHNIQUE OF CHEST WALL RESECTION

Chest wall involvement is often heralded by the clinical finding of pain associated with

a peripheral lesion seen abutting the chest wall on CT scan. In general, it is not possible to reliably differentiate chest wall invasion from simple abutment merely by looking at the CT scan. A posterolateral incision is made, and the latissimus dorsi muscle and serratus anterior muscles are either divided or mobilized if they are needed for pedicled muscle flaps. The chest is typically entered via the fifth intercostal space and exploration carried out. If the lesion involves the fifth rib, entry into the hemithorax should be either anterior or posterior to the presumed area of involvement. Before initiating the chest wall resection, palpation of the hilum and mediastinum should be carried out to ensure resectability. It serves little purpose to take down the chest wall block only to find locally advanced disease or diffuse pleural disease that precludes resection. The combination of mediastinal lymph node positivity and chest wall involvement portends a poor outcome. If there is any suspicion of nodal involvement, mediastinoscopy must be carried out before chest exploration. A positive mediastinum usually precludes chest wall resection outside of a protocol setting, although some surgeons proceed with resection after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Most studies have shown essentially no 5-year survivors with chest wall involvement and positive mediastinal lymph nodes.

a peripheral lesion seen abutting the chest wall on CT scan. In general, it is not possible to reliably differentiate chest wall invasion from simple abutment merely by looking at the CT scan. A posterolateral incision is made, and the latissimus dorsi muscle and serratus anterior muscles are either divided or mobilized if they are needed for pedicled muscle flaps. The chest is typically entered via the fifth intercostal space and exploration carried out. If the lesion involves the fifth rib, entry into the hemithorax should be either anterior or posterior to the presumed area of involvement. Before initiating the chest wall resection, palpation of the hilum and mediastinum should be carried out to ensure resectability. It serves little purpose to take down the chest wall block only to find locally advanced disease or diffuse pleural disease that precludes resection. The combination of mediastinal lymph node positivity and chest wall involvement portends a poor outcome. If there is any suspicion of nodal involvement, mediastinoscopy must be carried out before chest exploration. A positive mediastinum usually precludes chest wall resection outside of a protocol setting, although some surgeons proceed with resection after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Most studies have shown essentially no 5-year survivors with chest wall involvement and positive mediastinal lymph nodes.

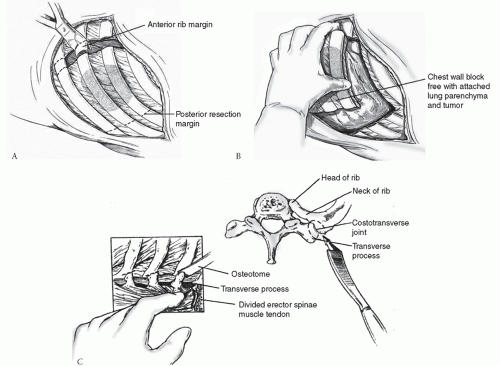

Once it has been determined that the tumor is resectable, the chest wall resection is begun. Depending on the location, the scapula may need to be mobilized off the chest wall, which requires division of the trapezius and rhomboid muscles. At least a portion of one rib above and one rib below the lesion should be resected. The extent of resection is determined by the intrathoracic exploration. The anterior portion of the resection is done first by determining the appropriate rib and incising the periosteum several centimeters anterior to the lesion. A wide excision should be performed to ensure negative margins. We prefer to take a 1-cm piece of rib and submit this separately at each level as the anterior resection margin (Fig. 25.1A). This move creates a small amount of space for ligation of the intercostal bundle at each level. Starting at the inferior extent of the resection and working superiorly, the anterior margin is taken at each level with the pleura excised as the resection proceeds. The intercostal muscles at the inferior and superior extent of the resection are divided along with the pleura, and the posterior portions of the

involved ribs are divided. There is no need to take a separate posterior margin at each level as is done anteriorly; this margin will be marked on the en bloc resection specimen. Depending on the location of the lesion, the posterior rib division may be either through the rib as demonstrated in Figure 25.1B or may require disarticulation of the rib from the respective transverse process of the spine as shown in Figure 25.1C. If there is any doubt, the rib should be disarticulated and, at times, even the transverse process may need to be resected. As always the intent is to have a negative resection margin; anything less (i.e., a positive margin) is associated with poor long-term survival.

involved ribs are divided. There is no need to take a separate posterior margin at each level as is done anteriorly; this margin will be marked on the en bloc resection specimen. Depending on the location of the lesion, the posterior rib division may be either through the rib as demonstrated in Figure 25.1B or may require disarticulation of the rib from the respective transverse process of the spine as shown in Figure 25.1C. If there is any doubt, the rib should be disarticulated and, at times, even the transverse process may need to be resected. As always the intent is to have a negative resection margin; anything less (i.e., a positive margin) is associated with poor long-term survival.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree