Cerebral Hyperperfusion after Carotid Artery Endarterectomy

MARCUS E. SEMEL, LIANGGE HSU, and C. KEITH OZAKI

Presentation

A 67-year-old male with a history of dyslipidemia, essential hypertension, and a chronically occluded left internal carotid artery (ICA) is referred to your office after his primary care physician (PCP) detects a right carotid bruit on routine physical examination. The patient takes aspirin, a beta-blocker, an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, and a statin. The PCP obtained a carotid duplex, which reveals a high-grade 80% to 99% stenosis of the right ICA with a peak systolic velocity of 462 cm/s, end diastolic velocity of 142 cm/s, and an occluded left ICA. A thorough history and physical examination does not identify any cardiac or neurologic symptoms/signs, and the exam is otherwise noncontributory. His blood pressure in the office is 148/66 mm Hg. Electrocardiogram is normal. The patient is offered and accepts a right carotid endarterectomy (CEA). In the meantime, he returns to his PCP for perioperative optimization, and the dose of his ACE inhibitor is increased. Several weeks later, he undergoes a right CEA. It is performed under general anesthesia with routine shunting and patch angioplasty—the operation is uncomplicated. In the postanesthesia care unit, he is neurologically intact. His initial blood pressure is 165/72 mm Hg but drifts down to 82/58 mm Hg after several hours. He is asymptomatic.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for hypotension after CEA includes hypovolemia, cardiac dysfunction, sepsis, anaphylaxis, and neurally mediated mechanisms. This last category includes autonomic dysfunction from stimulation of the carotid baroreceptors in the freshly endarterectomized bulb. Hypotension may also serve as an initial sign of an intracranial event.

Approach

Postoperative blood pressure instability after CEA demands a thorough bedside evaluation. The accuracy of the blood pressure reading should be verified. The therapeutic strategy depends on the etiology of the hypotension. If nonneural mechanisms (e.g., hypovolemia, cardiac dysfunction) are ruled out, and on examination the patient demonstrates no neurologic deficit suggestive of cerebral ischemia, then alpha agonists (e.g., phenylephrine) may be given via continuous infusion to maintain perfusion to vital organs.

Case Continued

Based on this patient’s low intraoperative fluid resuscitation record, early postoperative oliguria, unremarkable physical examination results, and normal ECG, intravascular volume depletion is determined to be the cause of his relatively low blood pressure. He receives 1 L of lactated Ringer’s solution. Immediately after receiving Ringer’s solution, the patient’s blood pressure returns to 140/80 mm Hg. Six hours later, his blood pressure is 184/97 mm Hg with a heart rate of 86 beats per minute (bpm), and he remains asymptomatic.

Differential Diagnosis

A common mechanism for postoperative hypertension after CEA is the endogenous hormonal response to pain or anxiety. Additionally, patients may have missed doses of chronic antihypertensive medications. Notably, other patients after CEA suffer idiopathic postoperative hypertension that stands outside of these known mechanisms.

Approach

Pain therapy is titrated to avoid oversedation, which would impair the ability to perform serial neurologic examinations. For hypertension that is not related to pain, sodium nitroprusside or nitroglycerin holds the advantage of rapid blood pressure reduction and short pharmacologic half-life (permits easy titration). When beta-adrenergic receptor blockade would also be beneficial, a short-acting beta-blocker infusion is another easily titrated medication.

Discussion

The relatively narrow risk/benefit ratio of CEA and the systemic atherosclerosis in these often high-risk patients demand close perioperative attention to minimize complications. In the situation of perioperative blood pressure instability, high vigilance is mandatory. Perioperative hypotension and hypertension have been associated with increased incidences of neurologic and cardiovascular events. Recently published data suggest an increased risk for 30-day mortality, stroke, and cardiac complications in patients with postoperative hemodynamic instability after CEA. Among patients receiving intravenous vasoactive medication after CEA, there was an increase in the 1-year risk for death or stroke.

There are no clearly defined criteria for an acceptable blood pressure range after CEA, and the clinician must consider the patient’s baseline pressure. Although founded on limited data, many clinicians would consider systolic pressures over 160 mm Hg or less than 100 mm Hg to be indications for intervention in the short term. Hypotension due to autonomic dysfunction usually resolves within 24 hours of CEA. Idiopathic hypertension after CEA is seen more commonly in patients with preoperative hypertension and high-grade carotid stenosis.

Case Continued

A short course of labetalol brings the patient’s blood pressure below 140 mm Hg with a pulse rate of 62 bpm. He is restarted on his ACE inhibitor and discharged to home on postoperative day 1. However, 48 hours postoperatively, he calls your office with the complaint of a throbbing frontotemporal right-sided headache. At your recommendation, he comes to the hospital’s emergency department where his blood pressure is 168/93 mm Hg, he is neurologically intact, and he receives acetaminophen without relief. Four hours later, he vomits and then suffers a grand mal seizure. He is admitted to the intensive care unit.

Differential Diagnosis

The symptoms of cerebral hyperperfusion are primarily neurologic with the distribution of potential diagnoses following suit. Patients may present with altered mental status, confusion, headache, cortical symptoms (ranging from hemiparesis/hemiplegia, hemianopsia, and aphasia to obtundation), seizure, and signs/symptoms of intracerebral hemorrhage.

Beyond hyperperfusion, altered mental status and confusion may be attributable to postoperative delirium or narcotic pain medication resulting in oversedation. The headache associated with cerebral hyperperfusion is ipsilateral with either a frontotemporal or a periorbital distribution but may be diffuse in nature. It is sometimes described as throbbing, but may be migrainous. As a result, migraine and cluster headaches appear on the differential, but even if the patient has a history of headaches, it is important to remain vigilant for post-CEA complications. Cortical symptoms raise concern for postoperative stroke and early after surgery should be considered the result of a technical complication until proven otherwise. Seizure may be due to stroke, hemorrhage, or trauma or may be medication induced. Intracerebral hemorrhage, which is the most feared complication of cerebral hyperperfusion, may also be the result of stroke, trauma, neoplasm, or uncontrolled hypertension.

Approach

An emergency duplex ultrasound scan confirms right ICA patency. Transcranial Doppler (TCD) can be used to measure cerebral blood flow velocity in the middle cerebral artery (MCA). The diameter of the MCA is not altered by autoregulation, and therefore, changes in velocity correlate well with changes in MCA perfusion. In cerebral hyperperfusion, TCD may show a 150% to 300% increase in the ipsilateral MCA velocity.

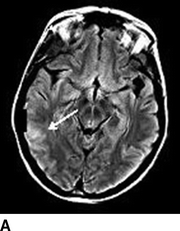

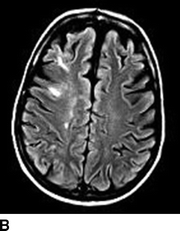

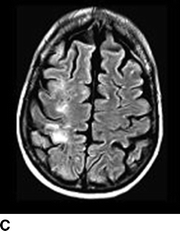

Computed tomography (CT) of the head without contrast serves as an initial screen for intracranial bleeding. Intracranial hypodensities on CT scan may be infarctions or edema. Notable CT findings include diffuse or patchy white matter edema, mass effect, petechial, or massive ipsilateral hemorrhage. Single photon emission CT (SPECT) can be useful for detecting alterations in brain perfusion and is sensitive for differentiating between ischemia and hyperperfusion. Similarly, diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can help distinguish between infarctions or edema. Notable MRI findings include white matter edema, focal infarction, and local versus more diffuse hemorrhage (Figs. 1 and 2).

FIGURE 1 A–C:Multiple FLAIR images demonstrate increased T2 signal of the subcortical white matter in the right MCA distribution (A, white arrow) without associated diffusion-weighted imaging abnormality consistent with hyperperfusion changes and not infarct.