IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ Current indications for carotid endarterectomy were reviewed in Chapter 3.1–3

■ In recent years, CTA and MRA have assumed preeminent roles in carotid intervention planning. Improved resolution has enabled highly accurate characterization of plaque morphology, which may provide useful guidance regarding plaque vulnerability during operative manipulation.

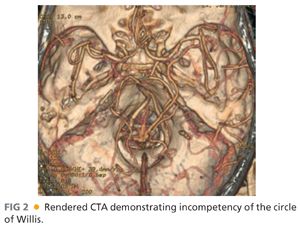

■ MRA and CTA also provide essential information regarding potential collateral arterial flow through the circle of Willis and the need for adjuvant maneuvers such as shunt placement during carotid revascularization (FIG 2).

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning for Distal Cervical Carotid Exposure

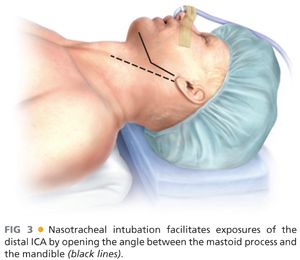

■ Knowledge of patient-specific cervical anatomy is essential to successful management of distal carotid disease. When recognized as necessary, specifying nasotracheal, rather than orotracheal, intubation for general endotracheal anesthesia is a simple and highly effective maneuver to improve exposure. Nasotracheal intubation allows the mouth to stay closed during surgery, providing more room between the ramus of the mandible and mastoid process for distal dissection.

■ Temporomandibular subluxation may further advantage carotid exposure cephalad to the C2 cervical spine. Subluxation of the ipsilateral mandibular condyle, performed via intraoral wiring, facilitates exposure from infratemporal ICA to the skull base. Subluxation is distinguished from dislocation, which is more injurious and can potentiate long-term temporomandibular joint pain syndromes.

Positioning

■ The patient is positioned supine, with the head extended and rotated away from the operative site. Shoulder rolls and shays are placed to stabilize the neck and optimize extension. The nasotracheal tube is secured over the head (FIG 3).

■ Arms are tucked to the patient’s side to allow the operator and the assistant to maneuver and stand comfortably. This position also facilitates C-arm positioning when needed.

■ The patient is placed in the “beach chair” position to limit venous hypertension (FIG 4).

TECHNIQUES

ANTERIOR APPROACH TO THE DISTAL INTERNAL CAROTID ARTERY

Incision

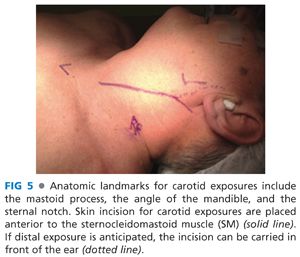

■ A vertical, rather than transverse, cervical incision is recommended for optimal distal ICA access (FIG 5).

■ Standard exposure of the carotid artery in the sheath was previously described in Chapter 3.

Exposure of the Internal Carotid Artery Distal to the Bifurcation

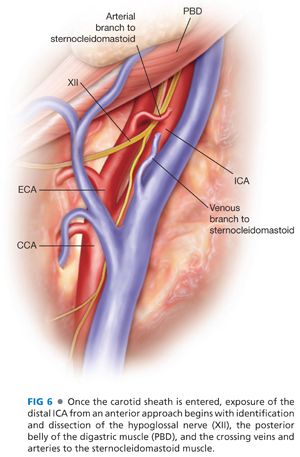

■ Key structures that lie superior to the carotid bifurcation are the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, the hypoglossal nerve, crossing veins from the sternocleidomastoid muscle to the internal jugular vein, and muscular arterioles of the posterior branches of the external carotid artery (ECA) (FIG 6).

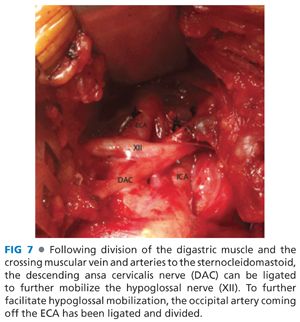

■ The hypoglossal nerve is identified safely using a posterolateral to anteromedial dissection of the ICA. Moving cephalad, the hypoglossal nerve is dissected free from the medial surface of the digastric muscle. Crossing artery and veins of the SCM often tether this nerve closer to the bifurcation. Meticulous identification and controlled division of these tethering vessels will enable mobilization of the nerve. Tracing the course of the descending branch of the ansa cervicalis back to the hypoglossal itself provides positive confirmation of the location and course of the nerve (FIG 7).

■ The posterior digastric muscle belly may be retracted or divided as required for exposure, following release of the adherent hypoglossal nerve.

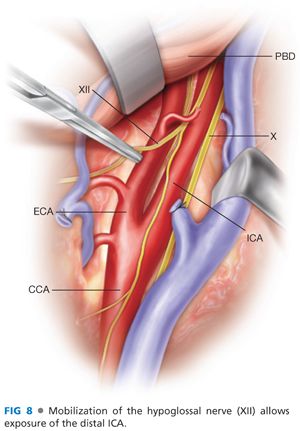

■ Additional cephalad exposure at this juncture requires division of the occipital branch of the ECA. This further releases the hypoglossal nerve. This maneuver also requires division of the styloid musculature (styloglossus, stylopharyngeus).

■ Continued cephalad dissection exposes the glossopharyngeal nerve, seen as a single or double trunk crossing the ICA anteriorly and coursing posterior to the external carotid. Care must be taken in separating the hypoglossal and glossopharyngeal nerves, as small motor fibers exiting the vagus nerve also course in this plane. Damage to these nerves or the glossopharyngeal can cause swallowing dysfunction. Classically, injury to the glossopharyngeal nerve in this region may impair the ability of the soft palate to rise sufficiently with swallowing to prevent nasopharyngeal liquid reflux.

■ When these steps are safely completed, the ICA may be adequately exposed for reconstruction up to the level of C2 (FIG 8). Further exposure to the level of C1 following this course requires styloidectomy and/or preoperative mandibular subluxation.

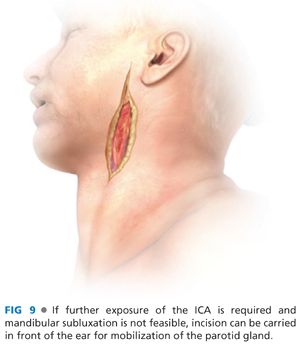

■ Distal dissection may also be facilitated by mobilization of the parotid gland and facial nerve. This is most safely accomplished with assistance from otolaryngologists or craniomaxillofacial surgeon. To provide this method of exposure, the skin incision is carried cephalad anterior to the ear (FIG 9). This enables mobilization of the parotid gland superiorly and medially.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree