Carotid Artery Dissection

ANDREW M. SOUTHERLAND, JENNIFER J. MAJERSIK, and BRADFORD B. WORRALL

Presentation

A 47-year-old right-handed man presented with abrupt onset right-sided head and neck pain while shoveling snow. Six hours later, he noticed his left hand was not working as well so his wife called 911. Past medical history is significant for migraine headaches with visual aura and mild hypertension, but no other vascular risk factors. Family history is negative for stroke or other vascular disease. On physical examination, his blood pressure is 153/93 mm Hg with vital signs otherwise stable. He has no cervical bruits, normal cardiac auscultation, and regular and symmetric pulses. Cranial nerve exam reveals mild right-sided tarsal lid ptosis and anisocoria (right pupil 2 mm, left 4 mm) more pronounced in the dark. Additional neurologic exam reveals a mild left pronator drift and weakness of the left hand with slowed finger tapping and 4/5 grip strength. Neurological exam is otherwise intact.

Differential Diagnosis

Abrupt onset of focal neurologic symptoms localizing to an arterial territory is always concerning for an acute stroke. In this case, differential diagnosis includes ischemic versus hemorrhagic stroke subtypes, complicated migraine headache given the head pain and his past history, or an acute neuromuscular injury given the association with exertional activity. Other causes of stroke in the young include thromboembolism from acquired or congenital cardiac disease; transient vasculopathies, such as reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS); genetic vasculopathies, such as moyamoya; or occult hypercoagulable states; the etiology remains cryptogenic in many cases. Hemorrhagic stroke subtypes, such as aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, should present with a more profound “worst headache of life.”

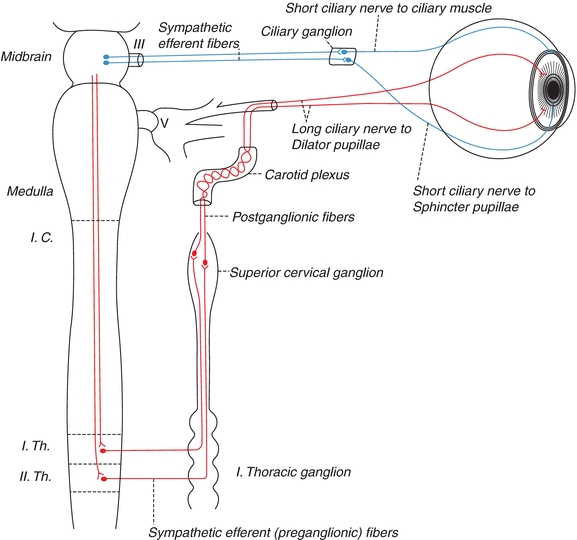

The key physical finding in this case is the presence of lid ptosis and miosis on the right, hallmark signs of oculosympathetic palsy or Horner’s syndrome, representing injury to the carotid plexus of ascending postganglionic sympathetic fibers innervating the superior tarsal and pupillary dilator muscles (Fig. 1). The constellation of abrupt head and neck pain, Horner’s syndrome, and stroke-like symptoms in a relatively young adult is consistent with cervical artery dissection and requires immediate vascular imaging of the cervicocerebral arteries.

Figure 1 Sympathetic trunk and carotid plexus (Gray’s Anatomy—public domain).

Workup

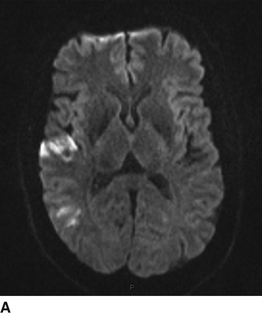

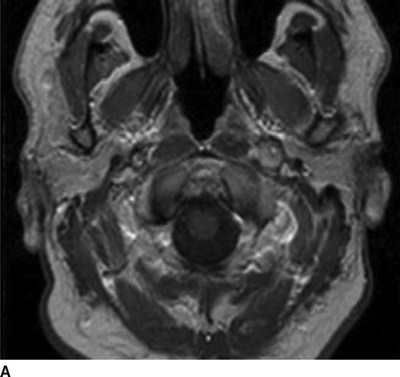

An MRI and MRA of the head and neck are obtained. On diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), brain MRI reveals wedge-shaped areas of restricted diffusion in the right frontal cortex, consistent with acute infarctions of likely thromboembolic origin (Fig. 2). Neck MRA demonstrates a “tapered” occlusion of the right internal carotid artery (ICA) several centimeters distal to the bifurcation (Fig. 3A). The left ICA has a “tonsillar loop” but is otherwise widely patent and regular (Fig. 3B). Intracranial MRA demonstrates delayed cross-filling of the right middle cerebral artery (MCA) from the left carotid circulation via a patent anterior communicating artery (AComm) (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 2 MRI/DWI sequences. A: Axial. B: Coronal.

FIGURE 3 MRA head and neck. A: Left ICA with tapered occlusion. B: Right ICA with tonsillar loop. C: Delayed cross-filling of right MCA via left carotid circulation and patent AComm.

Discussion

Cervical artery dissection (CeAD)—dissection of the carotid or vertebral arteries—is a significant cause of stroke in young and middle-aged adults, mostly occurring between the ages of 30 and 50 with women being younger than men at time of event. In contrast to other causes of ischemic stroke in older adults related to chronic vascular disease, CeAD typically occurs in young, healthy patients without known atherosclerosis or cardiovascular risk factors. A small proportion (less than 2%) can be attributed to known monogenic connective tissue disorders, such as vascular Ehlers-Danlos or Marfan’s syndrome, but most patients are phenotypically normal. Another 10% to 20% of cases are associated with fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) of the cervical arteries. The majority of cases are considered spontaneous and often associated with cervical neck exertion ranging from violent coughing to chiropractic manipulation. A subset results from major neck trauma involving cervical spine injuries with a majority from motor vehicle accidents (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Cervical Artery Dissection

In the spontaneous form, the true pathology leading to dissection is unknown but is likely multifactorial including both environmental and genetic predisposition to weakening of the arterial wall. Shear force exertions with lateral rotation or hyperextension of the neck leads to an intimal tear and intramural hematoma dissecting the medial or adventitial layers. Strokes occur by hematoma expansion occluding the true lumen contributing to large-artery territory infarcts or thromboemboli from the site of dissection occluding downstream vascular territories.

About 70% of CeAD cases present with stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA). Carotid dissections lead to stroke by either carotid occlusion from the intramural hematoma or thromboembolism from the site of intimal injury. Carotid dissection most often presents as a stroke or TIA in the MCA or anterior cerebral artery (ACA) territories. Vertebral artery dissection most often manifests as ischemia in the posterior circulation, presenting as an acute vestibular syndrome of vertigo and ataxia or a more circumscribed lateral medullary (Wallenberg) syndrome or cerebellar stroke. The latter is of particular concern in this young patient population given the subsequent risk for cerebellar edema and posterior fossa herniation as a neurologic emergency. Thromboembolic events may occur several days or even weeks after the initial dissection event, creating a high-risk period in need of optimal stroke prevention.

A remainder of cases present with local signs only, comprising pain, Horner’s syndrome, or cranial neuropathies from local arterial insufficiency to the nerve proper. The pain of carotid dissection is typically in the face or lateral neck, while vertebral artery dissections predispose to pain in the occipital or posterior cervical region—often described as tearing or cricking. Migraine or history of migraine headaches has also been associated with CeAD.

Up to 20% of cases of CeAD occur in multiple cervical arteries simultaneously, so called polyarterial clustering that suggests an underlying arteriopathy of unclear etiology. This is further suggested by reported associations with other nonatherosclerotic vasculopathies, including intracranial and aortic aneurysms, FMD, aortic root dilatation, and nonspecific arterial tortuosity and kinking.

Diagnosis and Treatment

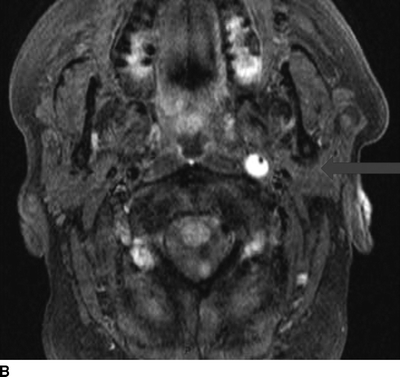

In the present case, the clinical presentation is confirmed by imaging as a diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke secondary to right ICA dissection with thromboembolic infarcts in the right MCA territory. The imaging diagnosis of CeAD depends on verifying the presence of intramural hematoma in the arterial wall. The gold standard is an MRI of the neck with T1 fat-saturated or fat-suppressed sequences highlighting arterial wall expansion and narrowing of the true artery lumen (Fig. 4). Additional radiologic signs of CeAD on vascular imaging include evidence of an intimal flap or extracranial dissecting aneurysm (Fig. 5). In the case of arterial stenosis or occlusion, a smooth tapering or flame-shaped appearance indicates expanding intramural hematoma, as opposed to an ulcerated plaque or abrupt occlusion more indicative of atherosclerosis or intraluminal thrombus. The layering hematoma of CeAD may also give the view of a luminal crescent or half moon in axial sequences on MRA or CTA (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 4 T1 MRI neck with (B) and without (A) fat suppression demonstrating intramural hematoma of the left internal carotid artery (arrow). The black dot represents the true lumen.