Carinal Resection

Elizabeth A. David

Garrett L. Walsh

INTRODUCTION

Carinal resections are some of the most technically challenging procedures in thoracic surgery and should be approached with great attention to detail. The preoperative evaluation should include a complete medical workup, oncologic staging, and careful operative planning from the surgical and anesthesia perspectives. Of paramount importance is the creation of a secure, well-vascularized anastomosis under minimal tension. A vast majority of carinal resections are performed for malignancies, but occasionally benign conditions can result in critical airway obstruction that mandates a carinal resection. Despite the high incidence of morbidity associated with these procedures, 1-year survival for malignant disease as high as 75% has been reported. Survival is significantly shorter in patients with unresectable lesions and is usually measured only in months.

PATIENT EVALUATION

The workup of a patient with a carinal mass is not dissimilar from the workup for routine lung cancer patients. Involvement of the carina by lung cancer histology is considered a T4 lesion. Careful attention to a complete oncologic staging as well as appropriate medical and cardiopulmonary clearance is mandatory. Patients should undergo cardiac clearance and pulmonary function testing especially in situations in which concomitant pulmonary parenchymal resection will be required. Consideration of comorbid conditions and assessment of nutritional status is required. Many patients with tracheal lesions that result in respiratory compromise are placed on steroids during their diagnostic workup and it is important to wean the patients either completely off steroids or to as low a dose as possible prior to the elective resection and reconstruction. Smoking cessation is also important to optimize healing of the airway anastomoses and facilitate secretion clearance in the postoperative period. Common diagnoses associated with carinal resections are listed in Table 10.1.

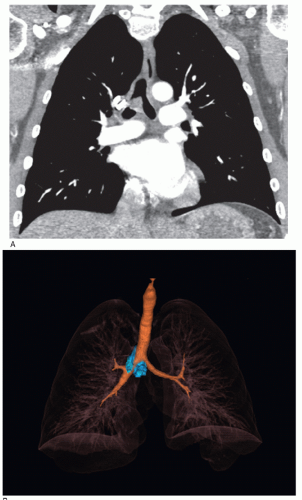

Computed tomographic (CT) scans are an essential part of the evaluation of tracheal lesions in patients who may require a carinal resection. CT provides information regarding the estimated length of the tracheal wall involvement and the endoluminal and extraluminal extent of disease. CT imaging can evaluate the size, shape, and number of mediastinal lymph nodes in the paratracheal, subcarinal, and supraclavicular stations. Pulmonary nodules suspicious for metastatic disease can also be detected. If available, 3D reconstructions based on CT images may help with operative planning (Fig. 10.1A and 10.1B). We use total body positron emission tomography (PET) fused with CT (PET/CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain to complete the staging workup for distant metastatic disease. The finding of distant metastatic disease, of course, is a contraindication to resection.

Bronchoscopy is a mandatory component of the evaluation of patients being considered for a carinal resection. Flexible bronchoscopy can be used to biopsy the lesion as well as assess the proximal and distal extent of the airway involvement. Rigid bronchoscopy using the tip of the bronchoscope to core through the tumor is useful to debulk obstructing lesions in a patient who presents with critical airway obstruction. This can quickly reestablish a patent airway with minimal bleeding in most cases. Lasers, argon plasma coagulators, and electrocautery techniques can also be used particularly for the more vascular tumors to control any bleeding if this should be encountered. Rigid bronchoscopy is also helpful to perform detailed measurement of the lesion, as well as assessing tumor fixation to the tracheal wall and overall tracheal mobility in relation to other mediastinal structures.

Mediastinal staging is required in these patients. N2 or N3 disease is difficult to characterize because of the central nature of these lesions, but we usually assign laterality based on the predominant involvement of the main stem bronchi. Patients demonstrating involvement of the mediastinal lymph nodes most commonly are treated with nonsurgical modalities (T4N2/N3 stage IIIB disease).

Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) offers additional diagnostic information in these patients. We use EBUS to obtain samples of lymph nodes for staging purposes at levels 2, 4, 7, and 11. In some cases we have also employed radial probe ultrasound to assess both the depth and extent of tracheal wall invasion.

We reserve the use of mediastinoscopy at the time of formal resection and favor EBUS for diagnostic purposes in the preoperative period. We do not recommend mediastinoscopy and a delayed carinal resection, as scar tissue that may compromise tracheal mobility at the time of resection will develop in the pretracheal plane in the time between the two procedures.

ANESTHETIC MANAGEMENT

A successful carinal resection requires excellent communication between the thoracic surgeon and an experienced thoracic anesthesiologist. For the safe conduct of the procedure, the anesthesiologist must be facile with multiple modes of ventilation, the performance of intraoperative bronchoscopy, and be committed to the planned extubation of the patient in the operating room suite immediately at the completion of the procedure. Immediate postprocedure extubation should be the goal of all team members; therefore, short-acting agents and careful fluid management are particularly important especially in situations where lung parenchyma resection is also planned, as in a carinal pneumonectomy.

The airway should be managed initially with an extra-long reinforced singlelumen tube that is placed with fiberoptic guidance. This will minimize trauma to

the airway and to the tumor itself so as to avoid hemorrhage into the distal airway. The extra-long tube (usually #7) provides a significant advantage in that it can be positioned in the trachea or bronchoscopically guided into the left or right main stem bronchus depending on the tumor location and the operative approach. The use of a double-lumen tube is not recommended as the tube is bulky and not easily maneuvered intraoperatively.

the airway and to the tumor itself so as to avoid hemorrhage into the distal airway. The extra-long tube (usually #7) provides a significant advantage in that it can be positioned in the trachea or bronchoscopically guided into the left or right main stem bronchus depending on the tumor location and the operative approach. The use of a double-lumen tube is not recommended as the tube is bulky and not easily maneuvered intraoperatively.

Table 10.1 Common Diagnoses Requiring Carinal Resection | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Prior to any incision in the airway, a focused discussion and simulation of the airway management between the surgeon and the anesthesiologist will ensure patient safety. A sterile reinforced endotracheal (ET) tube with extension tubing and appropriate and tested connectors is passed from the surgical field to allow for cross-table ventilation, prior to an airway incision. Once the airway has been opened, the sterile tube is placed into one of the main stem bronchi for ventilation. Throughout the resection and creation of the anastomosis it may be necessary to intermittently remove the ET tube from the airway to facilitate suture placement. During these periods of intermittent ventilation, hand ventilation by the anesthesiologist may be the best way to maintain oxygen saturation, prevent hypercarbia, and avoid barotrauma to the ventilated lung. In patients who do not tolerate intermittent ventilation, it may be necessary to use high frequency jet ventilation techniques. The surgeon and anesthesiologist, however, must be aware of the risks of air trapping and barotrauma associated with this method of ventilation.

In patients who present emergently with near-obstructing tracheal lesions, the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) systems has been described. Perfusion cannulas can be placed under local anesthesia prior to the induction of the general anesthetic in these patients who present in extremis. Centers who have described these techniques show comparable morbidity and mortality to more traditional approaches. The use of rigid bronchoscopy to core out and debulk the tumor, however, in most cases will eliminate the need and risks of CPB and will convert an emergent procedure into an elective resection. This is a lifesaving skill that all general thoracic surgeons need to acquire.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

Intraoperative Evaluation and Approaches

At the time of the resection, bronchoscopy is used to reassess the lesion and its resectability based on the total length of

required airway resection. In cases of cervical tracheal resections, it may be possible to resect up to 5 cm of the airway. We do not recommend greater than a 4-cm resection for more distal lesions, as this may result in excessive tension on the anastomosis. For lesions approached through a right thoracotomy, mediastinoscopy can be done at the time of the resection. This serves several purposes. First, mediastinal lymph nodes can be assessed by frozen section analysis. Second, the pretracheal tissue plane can be mobilized up to the level of the cricoid cartilage, a move that facilitates tracheal mobilization. Additionally, the left recurrent laryngeal nerve can be identified and mobilized away from the left side of the trachea, which may minimize the risk of nerve injury when the trachea is approached from the right chest.

required airway resection. In cases of cervical tracheal resections, it may be possible to resect up to 5 cm of the airway. We do not recommend greater than a 4-cm resection for more distal lesions, as this may result in excessive tension on the anastomosis. For lesions approached through a right thoracotomy, mediastinoscopy can be done at the time of the resection. This serves several purposes. First, mediastinal lymph nodes can be assessed by frozen section analysis. Second, the pretracheal tissue plane can be mobilized up to the level of the cricoid cartilage, a move that facilitates tracheal mobilization. Additionally, the left recurrent laryngeal nerve can be identified and mobilized away from the left side of the trachea, which may minimize the risk of nerve injury when the trachea is approached from the right chest.

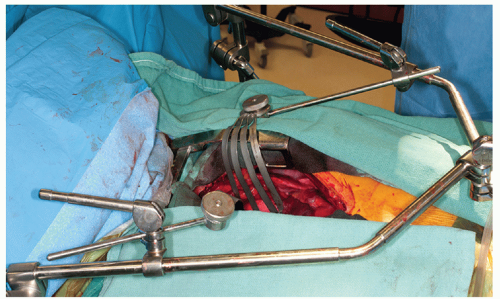

Tumors in the distal trachea, right main stem bronchus, and left main stem bronchus can be accessed through both the right chest and via the midline. The operative approaches to these tumors, therefore, are typically via a right posterolateral thoracotomy through the fourth or fifth intercostal space or through a median sternotomy. Although not contraindicated, approaching these tumors from the left chest can be challenging because of the location of the aortic arch and left pulmonary artery (LPA), both of which require mobilization to expose the carina. The left recurrent laryngeal nerve as it courses around the ligamentum arteriosum must be protected from injury and stretch during the mobilization of these structures.

Exposing the trachea through a median sternotomy requires mobilization of the ascending aorta to the patient’s left, the right pulmonary artery (RPA) caudally, and the superior vena cava (SVC) to the patient’s right. If at any time during the operation the patient becomes hypoxic, hypercarbic, or hypotensive, several physiological factors may be contributing to the clinical deterioration. Venous return may be compromised by excessive SVC retraction, cardiac output may be impeded by aortic retraction, and shunting may occur when the right lung is ventilated but the RPA is compressed resulting in a complete ventilation/perfusion mismatch. It may be necessary to adjust the retractors if hemodynamic or ventilatory compromise develops.

The initial dissection should include clearance of the subcarinal space of lymphatic tissue to facilitate exposure of the carina. Preservation of the blood supply to the lateral aspects of the main stem bronchi must be considered during this lymphadenectomy. If the lymph nodes have been previously sampled by EBUS, mediastinoscopy may not be required for cases approached with a median sternotomy. Blunt anterior dissection along the trachea, right main stem bronchus (RMB), and left main stem bronchus (LMB) is accomplished with ease through a median sternotomy. Mobilization of the membranous trachea can also be achieved with this approach, but posterior mobilization should take place after the airway has been transected. This mobilization is necessary to free the esophagus and right vagal nerve from the posterior aspect of the airway; however this dissection must be done judiciously to avoid injury and devascularization of the membranous trachea, which is perfused through small shared, esophageal branches. Preservation of the soft tissues along the lateral aspect of the trachea, RMB, and LMB is key to preserving blood supply to the surgical anastomoses; therefore blunt dissection and mobilization must be restricted to the anterior and posterior aspects of the airway (Figs. 10.2 and 10.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree