Cardial Incompetence and Associated Gastroesophageal Reflux

Katherine A. Barsness

Marleta Reynolds

Nelson and associates14 reported that up to 50% of all infants up to 3 months of age and 67% of infants 4 to 6 months of age have some degree of recurrent vomiting. When such infants are followed for 1 year, Nelson and colleagues15 found that most suffer no complications from the vomiting and that their symptoms disappear by 9 to 12 months of age. Local anatomic defects play a role in recurrent vomiting because infants with diaphragm and esophageal anomalies have a higher incidence of cardial incompetence, both during infancy and into early childhood. Neurologically impaired children are also prone to persistent cardial incompetence.

Although most infants have a normal lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure, Moroz and associates13 found the LES to be located above the diaphragm for the first 6 months of life. This prevents diaphragmatic crural contraction around the gastroesophageal junction and compression of the lower esophagus. Omari and colleagues16 found that most reflux episodes in preterm and term infants are associated with transient LES relaxation. Additionally, gastric emptying appears to be normal in the majority of infants with gastroesophageal reflux (GER).

A small percentage of infants will develop complications of vomiting, such as malnutrition, aspiration pneumonia, reactive airway disease, or sudden death. The esophageal and respiratory complications develop when normal protective reflexes are disturbed. Poor esophageal clearance of gastric acid will result in esophagitis. Laryngospasm, asthma, or recurrent pneumonia may develop when normal airway protective reflexes are inadequate. Many infants or children with neurologic disorders have associated poor esophageal motility and decreased esophageal acid clearance.

Symptoms

Vomiting is the most common symptom of cardial incompetence and may begin shortly after birth. It usually occurs after feedings and the vomit consists of ingested materials. In babies who develop esophagitis, coffee-ground emesis may become apparent. Failure to thrive leading to malnutrition develops as formula changes fail to relieve the vomiting.

Chronic aspiration may lead to nocturnal wheezing and chronic cough. Some infants and children are mistakenly treated for asthma. In children with known asthma, Debley and colleagues4 determined that the presence of weekly GER symptoms correlated with increased asthma-related morbidity and the use of asthma medications. Balson and colleagues,2 however, suggest that abnormal reflux can be diagnosed in some children with severe asthma and that these asthmatics should be evaluated and aggressively treated when reflux is found. Pneumonia may develop and require hospitalization and parenteral antibiotic therapy. Leape and associates11 confirmed an association of respiratory arrest and GER in 10 infants <6 months. Apnea may or may not be related to cardial incom- petence.

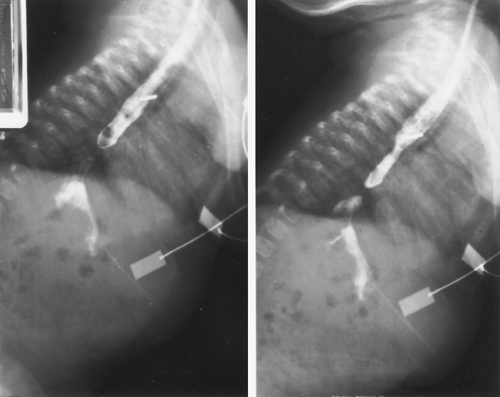

Strictures of the distal esophagus may develop after prolonged esophagitis. Although usually found in older children, we have treated several infants with severe strictures from prolonged reflux. Intolerance to feedings results when the stricture persists untreated (Fig. 154-1). Barrett’s esophagus is very rare in children. Hashem and colleagues10 reported a prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus of 2.5 per 1,000 children undergoing upper endoscopy. In this study, older age and hiatal hernia were identified as risk factors for the development of Barrett’s esophagus. Hassall9 reported that in many children with Barrett’s esophagus, the following comorbidities exist: neurologic impairment, chronic lung disease, esophageal atresia, and malignancies that have been treated with chemotherapy.

Diagnosis

A careful history is imperative in differentiating cardial incom- petence and associated GER from rumination and normal “spit-up.” A barium esophagogram and upper gastrointestinal series with fluoroscopic recording should be the initial studies of choice to rule out other surgical causes of vomiting. The gastroesophageal scintiscan can accurately diagnose reflux when an esophagogram has been normal. Twenty-four-hour pH monitoring is the most accurate means of testing for GER. A new technique mentioned by Lee and Rudolph12 of measuring intraluminal electrical impedance is under investigation to help evaluate the relation of nonacidic GER to apnea. Esophagoscopy and biopsy of esophageal mucosa confirm the presence of

esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus. They are also useful for excluding eosinophilic or infectious esophagitis.

esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus. They are also useful for excluding eosinophilic or infectious esophagitis.

Treatment

Medical Therapy

Conservative therapy can control symptoms in most children with cardial incompetence and GER. Dietary manipulations include increasing the frequency and decreasing the volume of feedings and thickening feedings with rice cereal. A 2-week trial of hypoallergenic formula should be attempted. Some authors recommend the prone head-up position. However, the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) precludes prone positioning during sleeping. The risk of SIDS must be weighed against the risk of complications of reflux. Recommendations by the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition (2001)22 include the use of acid-reducing agents for children with complicated GER. Although little prospective data exist, the usual first line of therapy in infants and children is the use of histamine-2 receptor antagonists. Proton pump inhibitors are used for infants and children failing first line therapy. Canani and colleagues3 have correlated the use of gastric acid suppression with an increased incidence of gastroenteritis and community-acquired pneumonia in otherwise healthy children.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree