Essentials of Diagnosis

General Considerations

Cardiac tumors arise either as a primary tumor of the heart or more commonly from metastasis of a distant noncardiac primary tumor. Because of the low incidence and nonspecific clinical manifestations, cardiac tumors have often been diagnosed incidentally during evaluation of a seemingly unrelated problem or misdiagnosed as other cardiac conditions. A high index of suspicion in combination with characteristic cardiovascular imaging study is essential for rapid identification of cardiac tumors.

Metastatic cardiac tumors are a 100-fold more common than primary tumors. Cardiac metastases often present as pericardial effusions; myocardial, coronary, and intracavitary involvement occur uncommonly, in order of decreasing frequency. The tumor that has the highest predilection for metastasis to the heart is disseminated malignant melanoma, which occurs in 50–65% of afflicted patients (Figure 32–1). The common noncardiac sources of metastatic cardiac neoplasms are neoplasm of the lungs, hematopoietic (lymphoma and leukemia) and gastrointestinal cancers (esophageal and liver), breast cancer, and renal cell carcinoma. Cancers from the respiratory system have been consistently shown to be the most common source of cardiac metastasis in different series; the relative proportion of other primary noncardiac malignancy for cardiac metastasis varies according to the local cancer incidence.

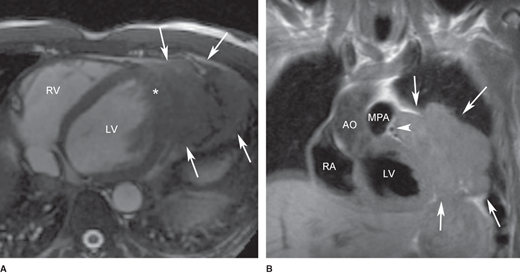

Figure 32–1.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the heart in a 50-year-old man who presented with dyspnea on exertion, 3 months after a diagnosis of melanoma on his back was made. A large pericardial mass was demonstrated on (A) bright blood-cine steady-state free precession image in axial plane. The arrows show the extension of the mass into the pleural space and possibly lung parenchyma. The asterisk indicates different texture of the myocardial signal, suggesting myocardial invasion of the mass. (B) Coronal black-blood T1-weighted image showing extension of the mass anteriorly and superiorly to impinge on the proximal left anterior descending artery (arrow head). Biopsy of the mass confirmed metastatic melanoma. AO, aorta; LV, left ventricle; MPA, main pulmonary artery; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle. (Courtesy of Karen Ordovas).

Malignant cells from any single source can metastasize to the heart via multiple routes and can often seed in multiple cardiac structures. For example, adenocarcinoma of the colon can metastasize to the heart by lymphatic or hematogenous spread, usually affecting first the pericardium and then the myocardium. Cardiac metastases that occur in patients with colon cancer are usually preceded by involvement of other organs. Metastases to the endocardium have been reported in renal cell carcinoma, which can also extend into the inferior vena cava, and the tumor thrombus occasionally involves the right atrium (Figure 32–2).

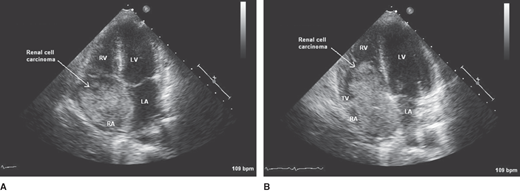

Figure 32–2.

Transthoracic echocardiogram in a 65-year-old man with a history of renal cell carcinoma in whom dyspnea and lower extremity edema developed. A: The apical four-chamber view shows a large mass most likely representing metastatic renal cell carcinoma in the right atrium. B: During diastole, the tumor prolapses through the tricuspid valve. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; TV, tricuspid valve.

Primary tumors of the heart are rare, with an incidence from 0.001–0.03% reported in unselected autopsy studies. Although myxoma has been traditionally reported to be the most frequent tumor type in adults, increasing utilization of imaging studies has revealed similar frequency of papillary fibroelastoma. In the pediatric population, rhabdomyomas represent the most common type (Table 32–1).

Benign tumors and tumor-like lesions Cardiac myxoma Rhabdomyoma Papillary fibroelastoma Lipoma Cardiac fibroma Hemangioma Histiocytoid cardiomyopathy Hamartoma of mature cardiac myocytes Adult cellular rhabdomyoma Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor Cystic tumor of the atrioventricular node Malignant tumors Metastatic tumors Angiosarcoma Rhabdomyosarcoma Fibrosarcoma and myxoid fibrosarcoma Leiomyosarcoma Liposarcoma Cardiac lymphomas Synovial sarcoma Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma Malignant pleomorphic fibrous histiocytoma Pericardial tumors Metastatic pericardial tumors Solitary fibrous tumor Malignant mesothelioma Germ cell tumors |

The majority (75–80%) of primary cardiac tumors are benign and therefore potentially curable.

These tumors account for approximately half of benign cardiac tumors and are usually found in patients between 30 and 60 years old, with a mean age of onset of 51 years. They occur predominantly in women; although most are isolated or sporadic, they can also be familial or complex. Less than 10% of myxomas are familial and are apparently transmitted in an autosomal dominant pattern. Familial myxoma presents earlier in life, with a mean age of onset of 25 years. Complex cardiac myxomas or the familial Carney complex may include such features as multiple pigmented skin lesions (lentigines), myxoid fibroadenomas of the breast, tumors of the pituitary and testes, and primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease. Carney complex appears to be genetically heterogenous with gene localization on chromosome 2p16 and chromosome 17q22-24. The majority of Carney complex appears to be caused by a mutation in the PRKAR1α gene that encodes the R1α regulatory subunit of the cyclic adenosine monophosphate–dependent protein kinase A (PKA). Patients with familial or complex myxomas are more likely than those with sporadic myxomas to have multiple (30–50%) and recurrent (12–22%) tumors. This occasional recurrence of myxomas and a few reported cases of invasion of surrounding tissue by the tumor suggest that myxomas have some low-grade malignant features.

Macroscopically, myxomas are pedunculated and gelatinous in consistency; the surface may be smooth, irregular, or friable. Friable or villous, myxomas are associated with a higher risk of embolization, whereas larger tumors with a smooth surface tend to present with obstructive cardiovascular symptoms. Microscopically, myxoma is characterized by islands of tumor cells with variable shapes (round, elongated, or polyhedral) scattered throughout pale-staining extracellular matrix. The tumor cells are thought to be derived from mesenchymal cardiomyogenic precursor cells.

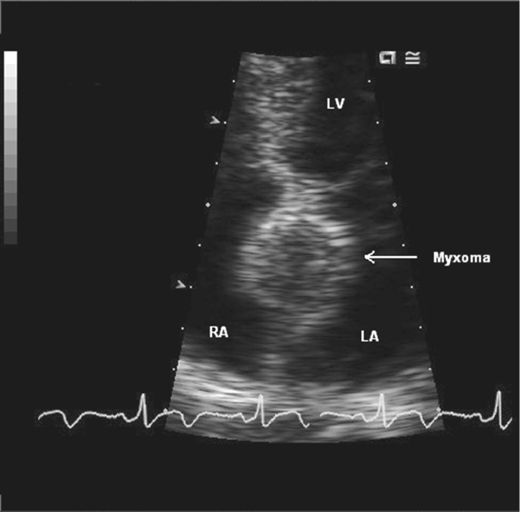

Most myxomas (74%) occur in the left atrium, although they can occur in any chamber (right atrium, 18%; right ventricle, 4%; left ventricle, 4%) or on any valve. They often arise from the endocardial surface of the left atrium with a stalk attached to the interatrial septum close to the fossa ovalis (Figure 32–3). When a myxoma occurs in the ventricles, it almost always originates from the free wall. Although asymptomatic myxomas have been recognized, most patients experience one or more effects from the classic triad of constitutional, embolic, and obstructive manifestations. (For details, refer to the section on Clinical Findings.)

These tumors account for 7–8% of cardiac tumors. They are usually discovered postmortem, with an autopsy incidence of 0.002–0.33%, although their premorbid detection rate is rising with the increasing use of echocardiography (Figure 32–4). They are usually found in patients older than 60 years of age, although they have been reported in patients from 3 to 86 years old. A profusion of names—cardiac papilloma, papillary fibroma, giant Lambl excrescence, and papillary endocardial tumor—have been used to describe what is properly a papillary fibroelastoma. These tumors (first described as small filiform projections on the cusps of aortic valves) have multiple papillary fronds and look like a sea anemone, attached to the endocardial surface of the valves by a small pedicle.

Figure 32–4.

Transesophageal echocardiogram to evaluate a mass found on a transthoracic echocardiogram in a 75-year-old man who suffered from dizziness. A: An irregular mass attached to the ventricular side of the anterior mitral leaflet is shown in this 113° long-axis view. The location on the downstream side of the valve and the frond-like surface are highly suggestive of a papillary fibroelastoma (arrow). B: Doppler signal demonstrating left ventricular outflow tract obstruction caused by the mass during systole. AMV, anterior mitral valve leaflet; AV, aortic valve; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle.

Papillary fibroelastomas can form a nidus for platelet and fibrin aggregation and lead to systemic or cerebrovascular emboli. They are most commonly identified on the valves, arising on the left-sided valvular structures much more frequently than the right-sided ones. A literature review of 725 reported cases of papillary fibroelastoma found 44% of the tumors arising from the aortic valve, followed by mitral valve in 35%, tricuspid valve in 15%, and pulmonary valve in 8%. Other less common locations, such as the chordae, papillary apparatuses, left ventricular septum, left ventricular outflow tract, left ventricular free wall, and the left atrium, have also been reported. Clinical manifestations include such conditions as cerebral embolism, myocardial infarction, sudden death, pulmonary embolism, and syncope. Surgical excision is generally recommended in the symptomatic individual. Mobile tumors have been suggested to be independent predictors of the occurrence of death or nonfatal embolization.

These tumors should not be confused with lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum, which is a nonneoplastic condition caused by adipose cell hyperplasia. Cardiac lipomas account for about 8% of primary cardiac tumors; they occur as solitary, circumscribed, encapsulated tumors with a wide range of size and weight. They can arise from epicardial surface and grow into the pericardial space, confined in the myocardium, or grow from subendocardium into the ventricular chamber.

Approximately three-quarters of all fibromas occur in the pediatric population. The second most common benign tumor of childhood, they have been reported in patients from age 2–57 years. Almost always solitary, fibromas can occur in any chamber but are most commonly found in the ventricular myocardium—usually in the anterior wall of the left ventricle and interventricular septum—and in the right ventricle (Figure 32–5). These tumors are often large, between 4 and 7 cm in diameter, and exert a mass effect. They are also associated with ventricular arrhythmias and heart failure; when arising from the ventricular septum, they can be associated with sudden death. Unlike lipoma, fibromas are not distinctly encapsulated, which makes complete resection more challenging.

Figure 32–5.

A: Coronal T2-weighted spin-echo magnetic resonance image of the heart through the level of the left ventricular anterior wall and the aortic valve. A mass is visualized emanating from the anterior wall of the left ventricle (arrow). The mass is mildly heterogeneous with mild T2 hypointensity relative to the myocardium. B: Transaxial T2-weighted image demonstrates predominantly peripheral enhancement. These findings are suggestive of a cardiac fibroma. (Courtesy of C. Higgins.)

Rhabdomyomas are the most common benign cardiac tumor in children, usually occurring before the age of 1 year. In fact, an intracavitary mass discovered incidentally in a pediatric patient is suggestive of rhabdomyoma until proven otherwise. There are frequently multiple tumors, occurring equally in the right and left ventricles or the atria; the valves are spared (Figure 32–6). They range in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters and are white to yellow. Rhabdomyomas are often associated with tuberous sclerosis, more frequently seen in those with mutations in the TSC2 gene compared to the TSC1 gene. Spontaneous regression is well established in the pediatric population, although tumor enlargement and de novo appearance have been observed during puberty. Unless the patient is symptomatic, surgical intervention is often unnecessary. When surgical resection is indicated, partial tumor resection has not been found to be inferior to complete resection.

Also known as histiocytoid cardiomyopathy or Purkinje cell hamartoma, these tumors are seen in children and infants. Hamartomas occur as flat sheets of cells on the endocardial or epicardial surfaces of the left ventricle and may present as ventricular arrhythmia. As many as 50% of cardiac hamartomas undergo involution with time, and recent data suggest that conservative management is appropriate. Controlling the arrhythmia medically, when possible, obviates the need for surgery.

Accounting for 5–10% of all primary benign cardiac tumors, these benign vascular tumors occur in three histologic types: capillary, cavernous, or mixed. They occur in a wide age distribution from age 2 weeks to 65 years old and can be isolated or be in multiple locations. They are located in any of the cardiac chambers. They usually appear as a hyperechoic lesion on echocardiogram, but cystic appearance has been noted (Figure 32–7).

Figure 32–7.

(A) Axial plane black-blood T2-weighted and (B) T2-weighted fast-spin echo with fat suppression images in a 60-year-old woman who had two right ventricular masses discovered incidentally on an echocardiogram. These masses are intermediate signal intensity between fat and myocardium, which increase in signal intensity with fat saturation pulse sequence. These characteristics are suggestive of hemangioma. LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium. (Courtesy of Karen Ordovas.)

Twenty five percent of all primary cardiac tumors have malignant characteristics.

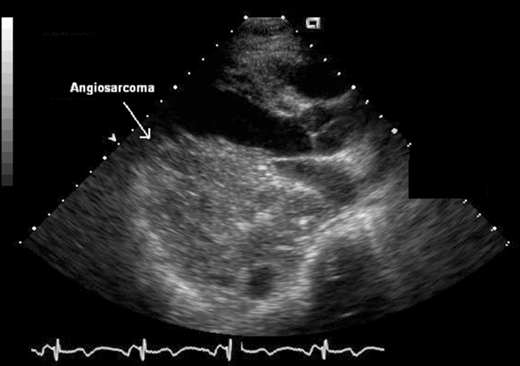

Comprising 50–75% of all primary cardiac malignancies, cardiac sarcomas are the most common malignant cardiac tumors in adults, with a predilection for patients between the third and fifth decades. Angiosarcomas are the most common histologic subtype, followed by rhabdomyosarcomas, fibrosarcomas, and osteosarcomas. Because angiosarcomas usually occur in the right atrium or pericardium, right-sided failure, pericardial disease, or vena caval obstruction can be the presenting manifestations. The tumor is extensively infiltrative of cardiac structures, and metastatic spread at the time of diagnosis is common (Figure 32–8). The tumor can be diagnosed by lung biopsy if pulmonary metastases are present. Cardiac Kaposi sarcoma is a type of angiosarcoma found in immunocompromised individuals, such as those with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Angiosarcomas are usually found on the epicardial or pericardial surface. Rhabdomyosarcomas have been reported in all age groups with a male predominance; in children, they constitute the most common malignant cardiac tumors. Fibrosarcomas have the characteristic “white fish flesh” appearance, composed of spindle cells. They occur equally in the left and right sides of the heart, are often multiple, extensively infiltrative, and protrude into a cardiac chamber or the pericardium. A valve is affected in half the cases. Osteosarcomas have been found in patients ranging in age from 24 to 67 years. They usually originate in the posterior wall of the left atrium, near the entrance of the pulmonary veins, and can be intramural or intracavitary. Osteosarcomas can metastasize to the thyroid, skin, and lungs. They exhibit the same gross and microscopic appearance as osteosarcoma of the bone. Leiomyosarcomas have rarely been reported in the heart. When they do occur, they are found in an older age group (> 55 years) and mainly in the posterior wall of the left atrium. Primary cardiac liposarcomas occur in younger patients (28–37 years) and are found in the right atrium or left ventricle and on the mitral valve.

Irrespective of histologic type, common features that predict more benign disease course are left atrium location, low-mitotic activity and scarce cellular pleomorphism, and absence of metastasis or necrosis. The overall prognosis of cardiac sarcomas is very poor, with mean survival ranging from 9.6 to 16.5 months.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree