First 3 minutes

Defibrillate within 3 minutes

Call for help/defibrillator

Begin CPR/bag mask ventilation

Analyze rhythm (distinguish shockable from non-shockable)

Shock if VF/VT

Resume compressions

Ongoing resuscitation

Secure airway

Monitor CPR quality

Administer drugs

Identify and treat reversible causes

Maximize neurologic outcome

Treat hypotension

Consider therapeutic hypothermia

Consider coronary reperfusion

Treat hyperglycemia

Assess prognosis

6.2.1 Basic Life Support (BLS) Phase

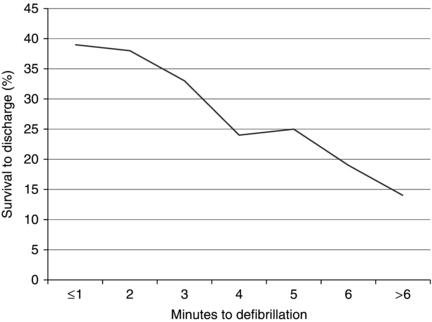

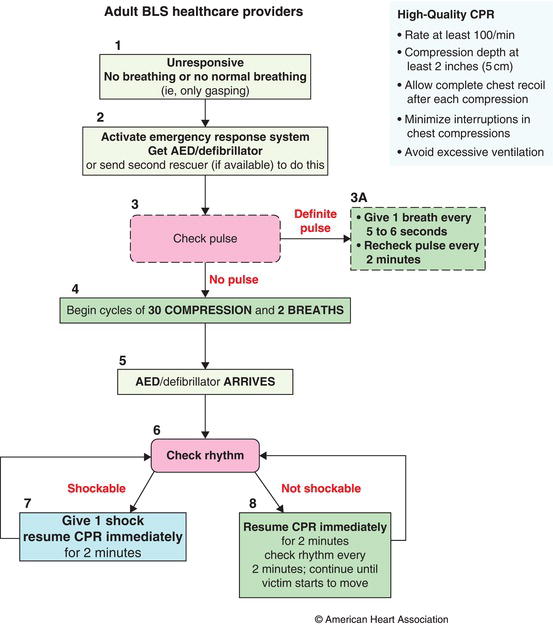

The first few minutes of a resuscitation are arguably the most important and yet the most chaotic, as providers arrive and the resuscitation team composes itself. Survival from cardiac arrest is correlated with time to CPR and in the case of VF/VT with time to first shock (Figure 6.1). During the BLS phase, the goal is to initiate chest compressions within 10 seconds and deliver a shock, if indicated, within 3 minutes. Thus, interventions that can delay defibrillation should be deferred until after this first attempt and remaining steps run in tandem, if multiple rescuers are present. (Figure 6.2)

Recognition and activation of emergency response.

Cardiac arrest should be suspected in any unresponsive patient who is not breathing normally (e.g. gasping or apneic). This should prompt an immediate activation of the hospital’s emergency plan and summon a defibrillator to the bedside, with additional rescuers. Cardiac arrest should be confirmed by carotid palpation for 5–10 seconds.

Initiation of CPR.

If no pulse is appreciated within 10 seconds, one rescuer should begin CPR by compressing the lower half of the patient’s sternum at a rate of at least 100/min and a depth of at least 2 inches, allowing full chest recoil between compressions. A second rescuer should prepare for ventilation. If the patient does not have an advanced airway in place at the time of cardiac arrest, chest compressions should be paused briefly after every 30 compressions to deliver 2 breaths with a bag-valve-mask, allowing 1 second per breath. In patients with advanced airways, asynchronous ventilation should be provided at a rate of 8–10/min without pausing chest compressions.

Defibrillation.

Meanwhile, the arriving defibrillator should be attached and turned on, continuing chest compressions until the monitor is able to pick up a rhythm. The rhythm should be analyzed quickly for the presence of a shockable rhythm. If VF or VT is present, a shock should be administered within 10 seconds of pausing chest compressions, using the manufacturer’s recommended energy level (or 200 Joules if unknown). If using a monophasic defibrillator, 360 Joules is administered. If a rescuer able to operate a manual defibrillator, is not readily available, an automated external defibrillator (AED) or AED-mode on a manual defibrillator should be used. However, AEDs can result in prolonged pauses in chest compression and may be associated with worse outcomes for those patients with PEA or asystole when compared to manual defibrillators. Chest compressions should be resumed immediately after defibrillation without rechecking the rhythm or pulse.

6.2.2 Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) Phase

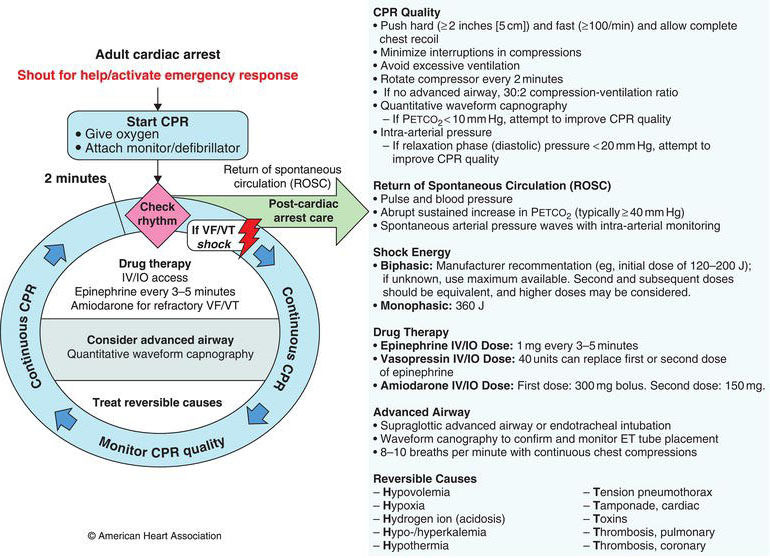

Following the first rhythm check, the resuscitation moves into the ACLS phase (Figure 6.3) with a goal of maintaining adequate perfusion and restoring a pulse. In this phase, the quality of CPR is paramount as is identifying and treating reversible causes.

Figure 6.2 BLS healthcare provider algorithm. (Source: Berg RA et al. 2010. Reproduced with permission of Wolters Kluwer Health).

Ensuring high CPR quality.

The key aspects of CPR quality are listed in Table 6.2. These include ensuring a depth of >2 inches, rate of at least 100/min, allowing full recoil, minimizing pauses in chest compression and avoiding hyperventilation. Interventions previously deferred in the BLS phase, such as advanced airway placement and intravenous or intraosseous (IV/IO) line placement, should be attempted during ongoing chest compressions. If a pause in compressions is required it should be timed with the next scheduled pause for rhythm check, compressor rotation, and possible defibrillation.

Figure 6.3 ACLS Cardiac Arrest Circular Algorithm. (Source: Neumar RW et al. 2010. Reproduced with permission of Wolters Kluwer Health).

Table 6.2 CPR Quality Components and Strategies for Improvement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree