Carcinoid Tumors

Juan C. Escalon

Frank C. Detterbeck

History

Carcinoid tumors constitute a relatively uncommon group of pulmonary neoplasms, being responsible for only 0.4% to 3% of resected lung cancers.11,14,67,85,90 The lung is the second most common site of origin for carcinoid tumors (next to the gastrointestinal tract).35 For many years, it was uncertain whether to classify these tumors as benign or malignant, which led to the ambiguous name carcinoid. Until the early 1970s, carcinoid tumors were also known as bronchial adenomas, implying a benign nature. In 1972, a subgroup known as atypical carcinoid tumors was described that had a more malignant histologic appearance (frequent mitotic figures) and demonstrated more aggressive clinical behavior (frequent lymph node and systemic metastases).3 There was also recognition that even typical carcinoid tumors have the capacity to metastasize, although they do so very slowly. All carcinoid tumors are therefore appropriately classified as malignant.

Classification

Carcinoid tumors are classified as neuroendocrine tumors arising from Kulchitzky cells of the bronchus. The World Health Organization (WHO) separates these tumors by pathologic features into typical carcinoids and atypical carcinoids.83 A typical carcinoid is defined as a tumor with neuroendocrine features, having <2 mitotic figures per 2 mm2 of viable tumor (which is equivalent to 10 high-power fields [hpfs]) and no evidence of necrosis. An atypical carcinoid has 2 to 10 mitotic figures per 10 hpfs (2 mm2), or evidence of necrosis or architectural disruption.83 Tumors with neuroendocrine features and ≥11 mitoses per 10 hpfs are classified as either large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) or small-cell lung cancer (SCLC). It is speculated that there may be a spectrum of disease from TC through atypical carcinoid and LCNEC to SCLC, but genetic expression and mutation analyses do not support this concept.2,7,84

The current classification was established in 1998.83 Previously, typical carcinoid and atypical carcinoid were classified according to an empiric schema,3 in which atypical carcinoid was defined as having 5 to 10 mitoses per 10 hpfs or other features including necrosis, pleomorphism, increased cellularity, and disorganization. The current schema was developed to be more reproducible and to better define prognostically distinct groups.83 This resulted in reassignment of approximately 30% of carcinoid tumors and an improvement in survival of both groups (10-year survival of 87% versus 73% for typical carcinoid and 35% versus 9% for atypical carcinoid).83 Other series in which there is overlap between patients classified by the old criteria33 and the new criteria34 also suggest better survival with the new criteria.

Overall, among studies of ≥50 patients, 16% of pulmonary carcinoid tumors are atypical carcinoid.6,9,15,26,28,29,30,34,41,54,61,64,65,72,76,78,85,88 In studies using the 1998 WHO classification scheme, 22% of pulmonary carcinoid tumors are atypical carcinoid,9,15,26,29,34,65 whereas among studies using the older scheme, 13% are atypical carcinoid.6,28,30,41,54,61,64,72,76,78,85,88

The new 1998 WHO classification83 is used throughout this chapter except where otherwise noted. The staging of carcinoid

tumors follows the same TNM system that is used for other lung cancers.36

tumors follows the same TNM system that is used for other lung cancers.36

Clinical Presentation

Demographics

Patients with pulmonary carcinoid tumors have a wide age distribution (4–86 years).34,44 The average median age of patients with pulmonary carcinoid tumors is 48 years,6,25,31,40,41,52,55,61,64,65,70,76,85 which is nearly 20 years younger than that of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Among studies reporting on ≥50 patients with pulmonary carcinoid tumors, the average percentage of women is 52% (range 42%–66%).3,6,9,15,26,28,29,30,31,34,40,41,46,52,55,56,62,64,65,72,76,78,85,88 The proportion of smokers is similar to that of the general population,9,15,26,28,30,56,62,72,86 although some have suggested a higher rate of smoking in patients with atypical carcinoid.30,56

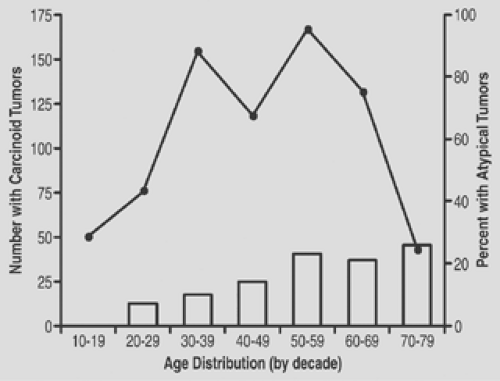

There is a bimodal distribution, with peaks at approximately 35 and 55 years of age (Fig. 122-1).6,41,52,62,78,88 The reason for this is unclear. The late peak is only partly explained by an increase in atypical carcinoid tumors in older patients.3,25,54,86 In a patient suspected to have a carcinoid tumor, the chance that this is an atypical carcinoid is approximately 25% in patients >50 and <10% in patients <30 years of age.6,41,62

Symptoms

Approximately one-third of patients were asymptomatic on presentation (Table 122-1) in an analysis of over 2,000 patients. In those with symptoms, the vast majority presented with cough, recurrent pneumonia, and hemoptysis. Similar findings were reported in other reviews of patients with bronchopulmonary carcinoids.39,44,76 Symptoms are typically seen with central tumors, whereas peripheral carcinoid tumors are usually asymptomatic and discovered incidentally.

Figure 122-1. Age distribution of patients with bronchial carcinoid tumors (line graph).6,41,52,62,78,88 and percentage of carcinoid tumors that are atypical by decades of age (bar graph).6,41,62 Data is based on reports using the old (1972) classification system.3 (From Kiser AC, Detterbeck FC. Carcinoid and mucoepidermoid tumors. In Detterbeck FC, Rivera MP, Socinski MA, et al., eds. Diagnosis and Treatment of Lung Cancer: An Evidence-Based Guide for the Practicing Clinician. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2001:379–393.) |

Table 122-1 Clinical Presentation of 2,135 Patients with Carcinoid Tumors | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

The diagnosis of a carcinoid tumor is often delayed, even in symptomatic patients. Only 71% of 91 patients were diagnosed within 1 year of the clinical presentation in one study, although 99% saw a physician within that year.52 In fact, 13% were not diagnosed until >5 years after the initial presentation.52 Many patients with a carcinoid tumor are treated for an infection or asthma for prolonged periods before the correct diagnosis is made.

Paraneoplastic Syndromes

Among studies of >50 patients, carcinoid syndrome was seen at presentation in only 0.7% of patients (17 of 2,496) with a bronchopulmonary carcinoid.6,9,13,15,30,34,41,46,52,55,61,64,65,78,82,85,88 Du- ring follow-up, an additional 2% to 5% of patients developed this syndrome, which consists of episodic flushing and diarrhea.4,6,55,64 An increased urinary level of the serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) is almost always found in such patients.17,55,76 In patients with pulmonary carcinoid tumors, carcinoid syndrome is almost exclusively seen when there are liver metastases (∼90% of cases).30,66 The incidence of this syndrome may be higher (5%–10%) in patients with an atypical carcinoid, consistent with the greater propensity of these tumors to metastasize.54 Although the classic carcinoid syndrome is rare, one study of 126 patients noted complaints of flushing in 12% of patients, diarrhea in 10%, and elevated 5-HIAA levels in 25%,40 suggesting that milder forms of the syndrome may be more frequent than is commonly appreciated. Similarly, a review76 of 1,875 patients with bronchopulmonary carcinoid tumors found an 11% incidence of flushing and 10% of diarrhea. This review reported an 8% incidence of carcinoid syndrome (vaguely defined) but included many patients with distant metastases.76

One review76 of patients with a carcinoid tumor in whom serotonin levels were measured, found these to be elevated in 47%, but other investigators have found it rarely elevated.26,40 Furthermore, it is unclear how this finding helps in patient evaluation. No parameters have been defined (sensitivity, specificity, false-negative and false-positive rate), to guide interpretation of results for bronchopulmonary carcinoid tumors. Thus this test

appears to be done more out of curiosity than actual clinical utility; its routine use is not recommended.26

appears to be done more out of curiosity than actual clinical utility; its routine use is not recommended.26

Cushing’s syndrome occurs in approximately 1% to 6% of patients with pulmonary carcinoid tumors,17,25,34,48,76,86,88 and bronchial carcinoids represent the most common source of ectopic production of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).17 In contrast to carcinoid syndrome, approximately 80% of patients with Cushing’s syndrome have localized disease.48 The tumor is not seen on a chest x-ray (CXR) in two-thirds of patients with a carcinoid tumor and Cushing’s syndrome, whereas a computed tomography (CT) demonstrates a lesion in most patients.48 The syndrome resolves after resection in most patients.48,54,88 Nearly 60% of these patients have lymph node involvement; most are peripheral tumors and approximately 80% are typical carcinoid tumors.34,63,74

Other syndromes associated with pulmonary carcinoid tumors have been reported very rarely.17 Several cases of acromegaly have been reported as a result of secretion of growth hormone by the tumor (all of which resolved after resection),10,17,32,34,77 and secretion of parathyroid hormone by a pulmonary carcinoid tumor has been documented in a patient with metastases.24 Valvular disease of the right side (!) of the heart has been noted rarely with pulmonary carcinoid tumors.66 Carcinoid crisis, a life-threatening complication of carcinoid syndrome, may be precipitated by diagnostic or therapeutic interventions, including initiation of chemotherapy, as noted in one report.17 This is manifested by flushing, confusion, coma, and either hypotension or hypertension. It can be treated by administration of somatostatin.17,37,50,51

Radiographic Appearance

Chest radiograph findings in patients with carcinoid tumors are usually nonspecific and consistent with the central location of the majority of these tumors. Most patients have either atelectasis (about 40%) or a central mass (about 25%), but a peripheral mass is seen in 30%.44 About 5% of patients have a normal CXR. The radiographic features of the primary tumor are not substantially different for typical carcinoid and atypical carcinoid. A tendency for atypical carcinoid tumors to be slightly larger has been suggested,34,55 but this has not been borne out in other studies.3,18,53,76 The best clues to the carcinoid subtype are the location (peripheral versus central) and evidence of nodal involvement (see subsequent sections).

Tumor Location

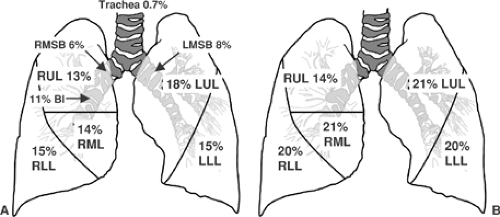

An average of 71% of typical carcinoid tumors were found to be central (range 51–98) in studies of >50 patients reporting such data.6,15,25,34,46,54,62,65,70,72,76,86 Of the central tumors (usually defined as visible by bronchoscope), most (75%) are located in a lobar or segmental bronchus. Tumors occurring in the mainstem bronchi are uncommon, and tracheal carcinoids are distinctly rare. The distribution of carcinoid tumors is shown schematically in Figure 122-2. The distribution among the lobes of the lung parallels the size of the lobes among peripheral tumors, but central tumors are disproportionately high in the right middle lobe and lingular portion of the left upper lobe.

The location of typical and atypical carcinoid tumors is slightly different. Approximately 50% of atypical carcinoid tumors are central in studies reporting these data (average 53%, range 32%–83%).6,25,34,54,62,65,70,76,86 It is more clinically useful, however, to start with a tumor location and then predict the cell type, as shown in Table 122-2. The large majority of central tumors are consistently atypical carcinoids, whereas the proportion of peripheral tumors that are atypical carcinoids is more variable. The cause for this variability is not clear; it does not appear related to the histologic classification scheme or the year of the study. This variability must be kept in mind in making predictions about peripheral tumors. Furthermore, it may be difficult to distinguish a peripheral carcinoid from other entities that appear as peripheral masses, particularly in older patients.

Diagnostic and Staging Tests

Computed Tomography

The radiographic features of a central or peripheral carcinoid tumor on a chest CT are usually quite typical, although the CT appearance by itself is not sufficiently unique to be reliable. Peripheral carcinoid tumors are typically homogeneous, rounded, and sharply demarcated masses (not spiculated). They usually occur deep within the lung parenchyma, making a wedge resection difficult. If prior films are available, the growth is usually indolent. Central carcinoid tumors often cause atelectasis and postobstructive pneumonitis. A mass within the airway can often be discerned. CT is important because there is frequently a large portion of tumor outside the airway that is not appreciated by bronchoscopy or CXR. A CT with intravenous contrast is essential for central tumors to define the relationship of the tumor

to adjacent vessels and better distinguish tumor from atelectatic lung.

to adjacent vessels and better distinguish tumor from atelectatic lung.

Table 122-2 Probability of Type of Carcinoid Tumor by Anatomic Locationa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A key issue is whether peribronchial or mediastinal lymph nodes are enlarged (again making intravenous contrast essential). Of course, node enlargement can be due to inflammation instead of tumor, particularly with central tumors. The reliability of node evaluation by CT in carcinoid tumors has not been well studied. In one report on 40 patients with central and peripheral carcinoid tumors, nodal assessment by CT demonstrated a sensitivity of 67%, specificity of 97%, false negative (FN) rate of 6%, and false positive (FP) rate of 20%.13 The extensive experience in NSCLC for CT assessment of mediastinal nodes demonstrates an FP rate of 40%, an FN rate of 20% to 25% in central tumors or those with N1 enlargement, and an FN rate of <10% in peripheral cN0 tumors.23 It seems appropriate to extrapolate the data from NSCLC to patients with carcinoid tumors until more data specific to carcinoid tumors become available.

Positron Emission Tomography

The role of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) in the diagnosis of carcinoids is evolving. There are conflicting data on the reliability of this modality for the detection of pulmonary carcinoids. The reported sensitivity of PET ranges from 14% to 100% for diagnosis of the primary tumor as malignant.16,27,45 Quantitative interpretation (standardized uptake value (SUV) <2.5 classified as benign) resulted in a sensitivity of 14% (PET imaging, n = 7)27 and 54% (integrated PET/CT imaging, n = 13)45 in two studies. Qualitative visual interpretation demonstrated a sensitivity of 75% (integrated PET/CT, n = 16)16 and 100% (integrated PET/CT, n = 13).45 It appears that the sensitivity is higher with atypical carcinoid versus typical carcinoid (80% versus 73%).16 The design of the reported studies does not allow calculation of specificity or of FN or FP rates for diagnosis of the primary tumor. There is a high proportion of peripherally located carcinoids (57%–81%) in these studies,16,27,45 likely reflecting a tendency to use PET imaging for indeterminate solitary pulmonary nodules (SPN).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree