CHAPTER 89 Bypass Conduit Options

History

In 1964 in Leningrad, Kolesov performed the first coronary artery bypass (CAB) graft, and at the same time he was the first to use the left internal thoracic artery (ITA), while working without cardiopulmonary bypass.1 Favaloro in Cleveland initiated the first CAB program in 1967,2 and in 1968 Green and colleagues began using the left ITA in New York.3 Although the saphenous vein (SV) ultimately became the most frequently used conduit, 100 bilateral ITA grafts were reported in 1974.4 Survival benefit for a single ITA compared with the SV was not demonstrated until 1986, and then a survival benefit for two ITAs compared with one ITA was shown in 1998, both by surgeons at the Cleveland Clinic.5,6

VENOUS CONDUITS

Greater Saphenous Vein

The media is composed of smooth muscle and few elastic fibers, and it has an internal elastic lamina. Wall thickness is too great for transluminal nourishment, so when the vasa vasorum are deprived of inflow, much of the smooth muscle dies and is replaced by fibrous tissue, and the vein then becomes a rigid tube without vasomotion or the ability to remodel in response to flow change.10 The endothelium can be damaged or lost despite careful harvesting, but it can regenerate.11 Native endothelial production of nitric oxide (NO) is less than that of arterial conduits, and it is further reduced in regenerated vein endothelium after grafting.12,13 Whether this is a factor in the neointimal hyperplasia that occurs after grafting and later atherosclerosis is unknown, although the role of NO in inhibiting adherence of platelets and neutrophils and proliferation of smooth muscle cells is well known. It is likely that the neointimal hyperplasia that occurs in all arterialized veins is a precursor to the accelerated (compared with native arteries or arterial conduits) atherosclerosis found microscopically by 2 years after surgery and found grossly in 70% to 80% of vein grafts at 10 years after operation. The venous drainage function of the SV is assumed by the deep venous system, but if the latter is obstructed by thrombotic disease, the SV should not be harvested.

Harvesting

After a single incision, or preferably multiple small incisions made over the course of the vein, sharp and blunt dissection can be used to expose the vein and its branches, which are divided between ligatures or clips. Care is taken to not place the clip too close to the vein wall, which could pinch the adventitia and distort or injure the wall directly. Likewise, the vein wall should not be handled by forceps, which should grasp only the adventitia. Endoscopic vein harvest has become popular in the past decade, with several small studies indicating a reduction in wound complications and good graft patency.14,15 However, a large randomized study of the use of edifoligide to reduce neointimal hyperplasia revealed a reduction in graft patency at 1 year in endoscopically harvested veins as opposed to veins obtained by open harvest. This report indicates a need to reassess endoscopic harvest, which is probably more traumatic than realized.16 Incisions are closed after vein harvest with or without drainage.

Grafting Strategy

Traditionally, one vein is used per target vessel, but patency for 1.5-mm or smaller coronary vessels is reduced,17 so sequential grafting, with smaller vessels receiving side-to-side anastomosis, gives better patency.18,19 Optimally, the distal anastomosis is to a 2.0-mm artery, but this may require using one vein to graft two coronary territories, which is appropriate. If vein length is limited, Y-grafting, as well as sequential grafting, is commonly performed and may also include proximal anastomosis to an arterial graft. A “snake graft” for the entire heart may be appropriate when the vein is limited, although in most patients the left ITA is grafted to the left anterior descending artery.

Patency

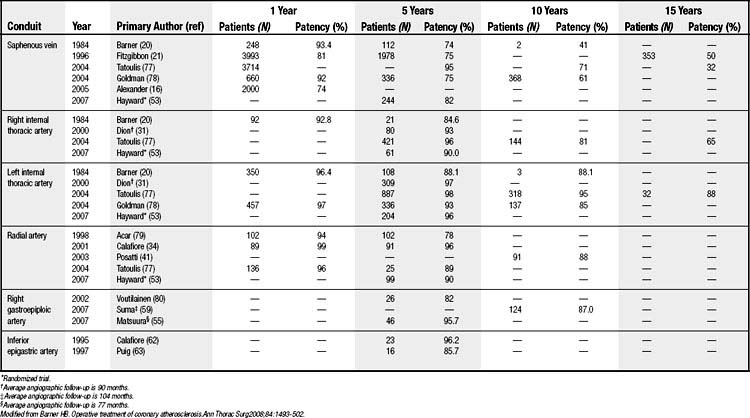

A 1-year patency of 81% to 93% reflects a poor-quality vein, technical problems, or low flow leading to layering of thrombus, which progresses to occlusion (Table 89-1). In the 1970s, more aggressive neointimal hyperplasia was seen, and it could result in stenosis and occasionally occlusion by 6 to 8 weeks postoperatively. This extreme response is rarely seen today because of improved harvesting techniques and vein management. However, a recent multisite randomized clinical trial with 3000 patients reported 1-year patency of 74%,16 which is less than the historic data and may represent a more realistic assessment than reports from single institutions (see Table 89-1).20,21 A 10-year patency of 60% to 70% falls to 32% to 50% at 15 years (see Table 89-1) because of progressive SV atherosclerosis—the Achilles heel of the SV graft.

Excellent (90%) 8.5-year SV patency has been achieved by harvesting the vein with a pedicle of fat.22 The vein is left in situ until it is used, but control veins were removed after mobilization and distended with saline at 300 mm Hg for 1 minute, which is known to damage the endothelium and media.22–24 This approach needs confirmation.

Lesser Saphenous Vein

As described for the greater SV, pharmacologic prophylaxis is unnecessary.

Creating aortic anastomoses with the lesser SV can be more difficult than with the greater SV. It is best employed as a Y-graft attached to the body or the aortic hood of the greater SV. Short-term patencies for the lesser SV and the greater SV are comparable, but there are no long-term data.25

ARTERIAL CONDUITS

Left Internal Thoracic Artery

The left ITA arises from the left subclavian artery opposite the vertebral artery origin and passes through the thoracic inlet, crossing dorsal to the subclavian vein with the phrenic nerve before passing deep to the endothoracic fascia just lateral to the sternal edge, which it follows to the sixth intercostal space. There it divides into the musculophrenic artery, having a lateral course, and the superior epigastric artery, which enters the rectus sheath.

The ITA is unique among the arterial conduits in that its muscular media has 6 to 12 elastic lamellae. The subintima lies on the prominent internal elastic lamina, which has few and small fenestrations in contrast to other small arteries, where more and larger fenestrations may allow entry of smooth muscle cells to the subintima and initiate plaque formation.26 The reduced smooth muscle mass results in less- vigorous contraction when exposed to agonists than is seen with the other arterial conduits. The ITA supplies flow to the anterior chest wall and sternum, which are also supplied by the intercostals, assisted by a vascular anterior sternal periosteum.

Harvesting

After sternotomy, the sternal leaf is elevated with a spreading retractor or a table-mounted pulling retractor. Historically, brachial plexus trauma, rib fracture, and costochondral separation occurred more commonly than they do now. The artery with its large medial vein can usually be seen and palpated in its mid course just beyond the sternal edge after the mediastinal fat is dissected from the chest wall. Many prefer to open the pleura widely, but others prefer to leave the pleura intact. It is common to harvest the left ITA with a 2-cm pedicle of endothoracic fascia, fatty areolar tissue, and two veins, performing all dissection with low-current electrocautery. Other surgeons clip all or some branches or use a combination of proximal clipping and distal cauterization. Skeletonization of the ITA is becoming popular because it provides a longer conduit, and there is less compromise of sternal blood flow and improved healing, so this should be used in diabetic patients having bilateral ITA harvesting.27,28

Pharmacology

Harvest-induced spasm can occur in the ITA and depends on forceps trauma, traction, electrocautery current, proximity to the artery, and direct trauma from dissection. Although spasm may resolve over time without treatment, good free flow should be demonstrated before grafting to ensure that the conduit has not been injured and that spasm is not irreversible. Papaverine, nitroglycerin, and nitroprusside are effective topically and are potent intraluminally, but care must be taken to avoid dissection with the cannula. Papaverine has a pH of 4.5 in saline and 7.4 when diluted with blood, but at 4 mg/mL there may be direct toxicity to endothelium.29 A concentration of 1 to 2 mg/mL is safe for extraluminal use, but this should be reduced to 0.5 mg/mL for intraluminal use. Intravenous infusions of nitroglycerin or nitroprusside are preferred by some both intraoperatively and postoperatively. Hydrostatic dilation should be avoided because of endothelial or transmural injury from pressure and because of the risk of intimal dissection.

Grafting Strategy

Some surgeons measure free flow, which is usually greater than 50 mL/min and may be as much as 150 mL/min depending on size, use of vasodilators, arterial pressure, and the degree of harvest-induced spasm. If the ITA is small (1.5 mm in diameter or less, distally), usually related to body size, free flow may be less than 20 mL/min but patency is not compromised.30 If flow appears too low, and marginally raising the blood pressure does not improve it, the cause could be spasm or intimal injury. Use of vasodilators (intraluminal papaverine in our experience) should correct the former.

Patency

In terms of patency, a graft from the left ITA to the left anterior descending artery is the gold standard for all conduits and target vessels. It is more than 95% at 1 year, 85% to 95% at 10 years, and 88% at 15 years (see Table 89-1). There is no loss of patency for sequential anastomoses in parallel, but there is a 10% decrease for crossing (diamond) anastomoses.31 Patency is unchanged for proximal circumflex branches (ramus intermedius, first obtuse marginal) and decreases 10% to 15% for distal circumflex branches.31 In contrast to the situation with other arterial conduits, the effect of decreasing stenosis (more competitive coronary flow) on graft patency is mild for the left anterior descending artery and slightly greater for other target vessels, and without a break point for decreasing stenosis.32

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree