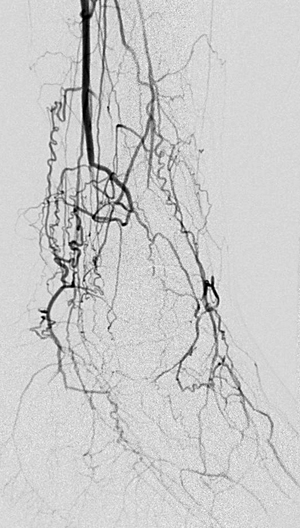

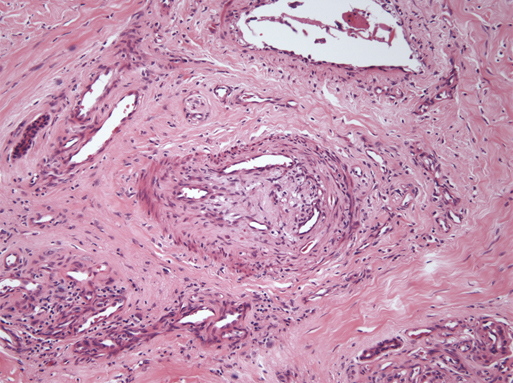

Diagnostic vascular laboratory assessment includes segmental blood pressure measurements of all four limbs. This can identify patients with proximal occlusive disease who could benefit from intervention. Digital blood pressure measurements with plethysmography often demonstrate flattened waveforms. Echocardiography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging can be useful to exclude proximal sources of thromboemboli. Contrast arteriography remains the best diagnostic study, especially when the diagnosis is in doubt or arterial reconstruction is contemplated. In these patients, the arteries appear normal until they reach the distal extremity, where multiple tapered or abrupt occlusions are seen. A corkscrew appearance of numerous collaterals around these occlusions is a classic finding (Figure 1). Amputation specimens exhibit grossly edematous arteries and periarterial tissues with occlusive thrombus. The lesions are segmental, and adjacent nerves and veins are secondarily involved with fibrous encasement. Histologic examination reveals polymorphonuclear leukocyte arterial wall invasion and mural or occlusive luminal thrombus. This thrombus contains multinucleated giant cells and leukocytes, which in later stages is subject to recanalization (Figure 2). Initially, these occlusive lesions lead to critical ischemia and tissue loss in the most distal parts of the extremity.

Buerger’s Disease

Diagnosis

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine