Biological Markers and Pathology of Mediastinal Lymphomas

Michael J. Kornstein

Lymphomas account for about 15% of all primary mediastinal masses.22,26,31,59,111 About one-third of the lymphomas are Hodgkin and two-thirds are non-Hodgkin. Almost all lymphomas are in the anterior and middle mediastinum; they are uncommon in the posterior compartment. In pediatric patients, up to 45% of anterior mediastinal masses are lymphomas.59,73 Mediastinal lymphomas most likely arise from the thymus or lymph nodes, hence their location in the anterior or middle mediastinum.

Some 60% of all Hodgkin lymphoma patients have mediastinal disease at presentation, with only 3% having tumor limited to intrathoracic sites.53,67 As for non-Hodgkin lymphomas, 20% involve the mediastinum, whereas <10% are limited to this site.52,98 The non-Hodgkin lymphomas make up a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by the clonal proliferation of lymphoid cells.

Classifications of Mediastinal Lymphomas

Over the past 30 years, numerous lymphoma classifications have been proposed.6,59 The Rappaport Classification and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Working Formulation were based only on tumor histopathology (e.g., nodular versus diffuse growth pattern, cell size, and appearance of the nuclei) (Table 190-1). Subsequently, studies divided lymphomas into B-cell versus T-cell phenotype on the basis of cell surface antigens. The Revised European–American Lymphoma (REAL) classification was proposed in 1994.41 It was revised and published as the World Health Organization (WHO) lymphoma classification in 200120,51(Table 190-2). This system divides lymphomas into B-cell neoplasms, T-cell (and natural killer cell) neoplasms, and Hodgkin lymphoma.

At present, the WHO classification is advocated for use. Nevertheless, knowledge of the previous classifications will continue to be useful, at least for communicating with those not acquainted with the more recent proposals and for understanding the older literature.

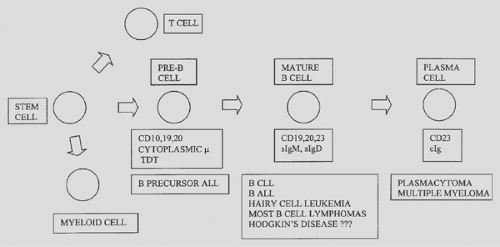

Like the lymphocytes from which they arise, lymphomas express either B- or T-cell markers17,59(Fig. 190-1). The B lymphocytes (and plasma cells) are immunoglobulin antibody-producing cells; therefore most B-cell lymphomas have surface and/or cytoplasmic immunoglobulin. The immunoglobulin molecule is composed of two heavy chains and two light chains. The heavy chains are alpha (IgA), gamma (IgG), mu (IgM), delta (IgD), or epsilon (IgE). Light chains are either kappa or lambda. Thus B cells express immunoglobulin having either kappa or lambda light chains. In a reactive process, approximately twice as many B cells (or plasma cells) have immunoglobulin with kappa light chains compared with lambda. In contrast, in a B-cell lymphoma, the B cells are clonal and have either kappa or lambda light chains. Hence the study of kappa and lambda light chains may be helpful in discriminating between a reactive (benign) lymphocyte population and a B-cell lymphoma.

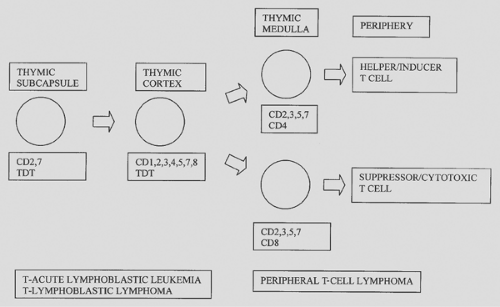

Figure 190-2 diagrams T-cell development in the thymus. The earliest T cells express CD2 and 7 and are located in the subcapsular areas of the thymus.59,63 With increasing development, the T cells also express CD1, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 8 and move to the thymic cortex. As the cells move to the medulla, they acquire a mature phenotype with loss of CD1 and retention of either CD4 or CD8. The cells then migrate from the thymus as helper/inducer T cells (CD4) or suppressor/cytotoxic T cells (CD8+).

A wide range of antibody reagents is available to characterize cell antigen expression (Table 190-3). These studies can be performed on tissue sections or cytospin preparations by immunochemistry or in cell suspensions by flow cytometry. Initially, all studies for lymphocyte surface antigens required fresh or frozen tissue. Currently, techniques have advanced, and many of the antigens can be studied by immunochemistry using routinely processed formalin-fixed specimens.45

Studies of DNA also may help in characterizing lymphomas.70 As lymphocytes mature, they undergo rearrangement of their DNA to produce immunoglobulin (B cells) or antigen receptors (T cells). On this basis, molecular biology techniques, including Southern blotting and the polymerase chain reaction, can determine whether a population of lymphocytes includes a clone of cells. Finding a clonal population of lymphoid cells in a tissue specimen usually indicates a lymphoma. Also, specific gene rearrangements are associated with some lymphomas.

Table 190-1 Working Formulation for Clinical Usage | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lymphoblastic Lymphoma

Lymphoblastic lymphoma has distinct clinical and pathologic features.59,101 This neoplasm is most common in children, among whom it accounts for 30% to 50% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.40,55 In adults, this tumor is uncommon and comprises only 5% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas.92 In children, the median age is 9 years, and it is seen twice as often in boys as in girls. Up to 75% of pediatric patients have a mediastinal mass. Most patients present with disseminated disease. Other than the mediastinum, sites of involvement may include extrathoracic lymph nodes, bone marrow, the central nervous system, head and neck, lung, pleura, liver, pericardium, peritoneum, skin, and gonads.

Lymphoblastic lymphoma is closely related to acute lymphoblastic leukemia.106 Both disorders generally involve lymph nodes, thymus, or both. However, leukemia is diagnosed if the patient also has significant bone marrow involvement. Lymphoblastic lymphoma is diagnosed when the patient has fewer than 25% lymphoblasts in the bone marrow.

Histologically, lymphoblastic lymphoma is a diffuse infiltrate of immature lymphoid cells (Fig. 190-3). The tumor cells are 12 mm in diameter (i.e., intermediate in size between small lymphocytic lymphoma and large cell lymphoma). The nuclei have finely dispersed chromatin without prominent nucleoli. In contrast to most other mediastinal lymphomas, fibrosis is scant. Tissue sections of lymphoblastic lymphoma show extensive effacement by round, blue cells. The tumor cells have a high rate of proliferation, as evidenced by frequent mitotic figures and numerous tingible-body macrophages. Necrosis is often widespread. Biopsy samples may consist entirely of necrotic tumor. Another problem is that the cells are damaged easily. Crush artifact in a tissue biopsy may be so extensive as to obscure the diagnosis. Wright-stained cytologic preparations (e.g., touch imprint, fine-needle aspiration) are helpful in that the morphology of individual cells is better appreciated. For a touch imprint, the tumor is gently touched to the slide. These imprint preparations demonstrate the diffuse chromatin pattern, basophilic cytoplasm, and occasional vacuoles.

Immunologically, mediastinal lymphoblastic lymphoma almost always has an immature T-cell phenotype. Rarely, precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma presents with mediastinal disease.65 Lymphoblastic lymphoma of either T- or B-cell origin is positive for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TDT), a marker of immature lymphoid cells. TDT can be demonstrated in routinely processed tissue, as can other markers commonly expressed by lymphoblastic lymphoma, including CD99 (MIC2) and CD34.94 However, no single marker should be relied on for diagnosis because none is entirely specific. For example, CD99 is expressed in other small round cell tumors of childhood. Mathewson and colleagues68 have reported that even TDT may be expressed in nonlymphoid small round cell tumors. The finding of immature lymphoid cells is not specific for lymphoblastic lymphoma. TDT-positive lymphoid cells have been reported in benign reactive lymph nodes from children.78 Immature T cells are also present in normal thymus, thymic hyperplasia, and lymphocytic thymoma. Most commonly, the tumor phenotype in mediastinal lymphoblastic lymphoma corresponds to the stage of cortical thymic lymphocyte differentiation, in which the cells express the T-cell antigens CD1, 2, 4, 7, and 8.24,91 Alternatively, the phenotype may correspond to an earlier stage of differentiation in which the cells express only CD2, 5, 7, or all three, or a later stage with additional expression of either CD4 or CD8. The level of differentiation does not consistently influence prognosis, although relatively few cases have been studied in this regard.

Lymphoblastic lymphomas expressing the natural killer cell phenotype (CD56+) have been described. Natural killer cells are granular lymphocytes that are positive for CD16 and CD56 but lack surface CD3. These cells have major histocompatibility antigen-unrestricted cytotoxicity. Lymphomas expressing the natural killer cell phenotype have a predilection for the nasopharyngeal region and skin. Koita and associates58 reported a lymphoma with nasal and mediastinal involvement that histologically appeared lymphoblastic and expressed TDT.

Uncommonly, lymphoblastic lymphoma with a precursor B-cell phenotype involves the mediastinum.65

Uncommonly, lymphoblastic lymphoma with a precursor B-cell phenotype involves the mediastinum.65

Table 190-2 World Health Organization Classification of Neoplastic Diseases of the Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Lymphoblastic lymphoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of a mediastinal tumor, particularly in pediatric patients. These patients typically have peripheral lymphadenopathy. Pathologic diagnosis usually can be made on a fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy of a peripheral lymph node.109 The FNA biopsy sample can be studied morphologically on Wright-stained smears. The diagnosis can be confirmed by immunologic studies for cell surface markers performed by flow cytometry on cell suspensions or by immunocytochemistry on cytospin preparations. In a mediastinal biopsy, lymphoblastic lymphoma must be distinguished from a lymphocytic thymoma and thymic hyperplasia. A thymoma is a tumor of thymic epithelial cells, which should be identifiable by immunohistochemistry for cytokeratin. Thymic tissue has a lobular structure with cortex and medulla. This differential diagnosis can be difficult on a fine-needle aspirate of a mediastinal mass. In particular, lymphoblastic lymphoma involving the thymus can be impossible to distinguish from a lymphocytic thymoma. Nevertheless, FNA biopsy samples have been used successfully to diagnose mediastinal lymphoma.46 Flow cytometry can be used reliably in the diagnosis of lymphoblastic

lymphoma and in its distinction from thymic hyperplasia and thymoma.38,64 One caution is that steroid treatment prior to biopsy may interfere with the histopathologic diagnosis.15 In most cases, whether by FNA or core-needle biopsy, the combination of the appropriate clinical setting, the characteristic morphology, and the early T-cell phenotype should allow for the proper diagnosis.93

lymphoma and in its distinction from thymic hyperplasia and thymoma.38,64 One caution is that steroid treatment prior to biopsy may interfere with the histopathologic diagnosis.15 In most cases, whether by FNA or core-needle biopsy, the combination of the appropriate clinical setting, the characteristic morphology, and the early T-cell phenotype should allow for the proper diagnosis.93

Figure 190-2. T-cell surface markers: correlation with differentiation in thymus and neoplasia. TDT, terminal desoxynucleotidyl transferase. |

Table 190-3 Nomenclature for Lymphocyte Surface Antigens (Cd Markers) Useful in Hematopathology | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Mediastinal Large B-cell Lymphoma

Numerous series and reviews of mediastinal large cell lympho- mas have been published.1,4,5,7,8,14,18,21,27,32,49,57,59,60,61,62,75,103,107,118 Evidence favors the concept that mediastinal large cell lymphoma has clinical and pathologic features distinct from large cell lymphomas of other sites. Mediastinal large cell lymphoma usually occurs in young adults (median age 30 years, range 10–71). Women predominate over men in a 2:1 ratio. Most presenting symptoms relate to the local effects of the anterior mediastinal mass and include cough, dyspnea, chest pain, dysphagia, hemoptysis, and superior vena cava syndrome; fever, night sweats, and weight loss (B symptoms) are present in one-third of patients. Depending on the study, 13% to 54% of patients have extrathoracic disease—commonly of the supraclavicular, axillary, or intra-abdominal lymph nodes—at presentation. Bone marrow involvement is uncommon. A case report by Stein and associates97 describes a mediastinal large cell lymphoma complicated by a pneumothorax. Mediastinal large cell lymphoma in children (ages 10 to 17 years) has features similar to those in adults.66,81

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree