Best Medical Therapy in Asymptomatic Carotid Stenosis

VIJAIGANESH NAGARAJAN and ADITYA M. SHARMA

Presentation

A 78-year-old female with a history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension visited her primary physician for regular 6-month follow-up visit. She denied history of stroke or any symptoms suggestive of transient ischemic attacks (TIA). Her heart rate was 68 beats per minute and blood pressure was 142/92 mm Hg. Her clinical examination showed normal cardiovascular examination apart from left carotid bruit. Her HbA1c was 5.8%. Her lipid profile showed low-density lipoprotein (LDL) of 110 mg/dL and high-density lipoprotein of 42 mg/dL. She was taking metformin and metoprolol regularly.

Differential Diagnosis

Bruits are abnormal vascular sounds associated with turbulent, nonlaminar blood flow secondary to a stenotic lesion in an artery. The site of maximal intensity of the bruit gives us information regarding the possible vessel involved. Bruits heard close to the angle of the jaw are more specific for carotid artery stenosis as the bifurcation usually occurs at the level of thyroid cartilage. Other possibilities include cardiac murmurs radiating to carotids, cervical venous hum from neck veins and bruits secondary to intracranial arteriovenous malformations, and fibromuscular dysplasia. Supraclavicular bruits sometimes indicate subclavian stenosis.

Although screening for carotid artery disease is not usually advised in asymptomatic patients, carotid bruits identified on physical examination will often be evaluated for carotid stenosis. Sauve et al. investigated about carotid bruits in 1994 (NASCET trial data) and noted that the sensitivity and specificity of focal ipsilateral carotid bruit were 63% and 61%, respectively, to detect a high-grade carotid stenosis. Absence of a bruit was not a reliable marker to exclude significant carotid artery disease. In a recent meta-analysis including all studies published from 1966 to 2009, risk of TIA and stroke was significantly increased in patients with carotid bruit.

Stroke is the fourth leading cause of death and the leading cause of disability in the United States. Atherosclerosis in cervical arteries likely contributes to 15% to 20% of ischemic strokes. Hence in our patient, the next best step would be duplex ultrasonography of carotid vessels (Class IIa recommendation).

Workup of Patient

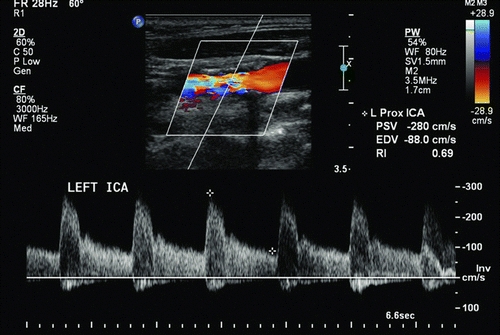

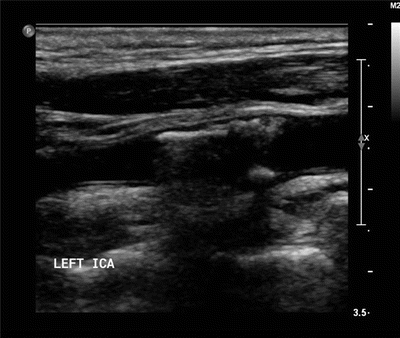

Ultrasonography in this patient showed >70% stenosis of the left carotid artery with peak systolic velocity of 280 cm/s, end diastolic velocity of 88 cm/s, and ratio of internal carotid (IC) to common carotid artery peak systolic velocity was 3.4 (Figs. 1 and 2). After being counseled about the risks and benefits of carotid intervention, the patient preferred not to undergo any revascularization. She was referred to a vascular medicine physician for optimal medical management for her carotid disease.

Figure 1 Proximal left internal carotid artery shows elevated peak systolic velocities.

Figure 2 Gray-scale image of the proximal left internal carotid revealing echogenic calcified plaque.

Recommendations for Carotid Revascularization

Current guidelines recommend revascularization only in asymptomatic patients with carotid stenosis of greater than 70% based on noninvasive imaging or more than 60% as documented by catheter angiography.

Medical Management and Risk Factor Modification

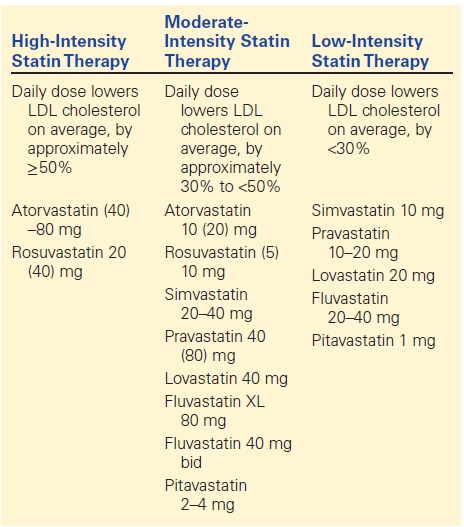

Medical optimization is a major component of management of carotid artery stenosis. Most of the trials evaluating surgical treatment options included optimal medical management in surgical arm as well. Modern medical therapy includes antiplatelet agents and statins, and aggressive risk factor modification (hypertension, cigarette smoking, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia) has dramatically reduced incidence of stroke and other cardiovascular morbidities, such as myocardial infarction (MI) and vascular deaths (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Differentiation of Various Statins with Doses Characterizing Them as Low-, Moderate-, or High-Intensity Statins

Antiplatelet Agents

The current multisocietal vascular guidelines recommend antiplatelet agents for patients with nonobstructive, as well as obstructive atherosclerotic extracranial carotid artery stenosis. Patients with carotid atherosclerosis are at increased risk of having atherosclerosis in other vascular beds, such as the coronaries. Antiplatelet agents are recommended for prevention of MI and other ischemic cardiovascular events.

The recommended drug therapy is either aspirin alone or clopidogrel alone or the combination of aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole. The dose of aspirin varied widely between trials, and hence a dose range of 75 mg daily to 325 mg daily has been recommended. There is no evidence to recommend using combination of aspirin and clopidogrel over using a single antiplatelet agent. In fact, current guidelines recommend against use of dual antiplatelet agents, such as aspirin and clopidogrel together, for asymptomatic carotid stenosis as it does not provide any additional benefit in reducing ischemic events but increases risk of bleeding. Dual antiplatelet therapy is only reserved for patients with other reasons to be on them, such as recently placed coronary stents, who also additionally have asymptomatic carotid stenosis.

Anticoagulant therapy with warfarin or the novel anticoagulants is not generally recommended for patients with carotid artery disease with or without symptoms. The Warfarin-aspirin recurrent stroke study (WARSS) investigators performed a subgroup analysis on patients with stroke and large artery stenosis/occlusion and found no beneficial effect seen with warfarin over antiplatelet agents. But if patients have other indications for anticoagulation, like high-risk atrial fibrillation, cardioembolic stroke, or prosthetic heart valve, then anticoagulation may be recommended in such patients.

Statins

Statins have shown been to reduce ischemic stroke and overall cardiovascular risk in patients with carotid atherosclerosis. This beneficial effect is seen even if the baseline lipid levels are “normal.” The SPARCL trial showed the benefit of atorvastatin in decreasing the incidence of ischemic stroke even with baseline normal LDL levels (100 to 190 mg/dL) by 22%. Two separate meta-analysis showed a 20% to 22% ischemic stroke risk reduction with use of statin therapy. This benefit is more prominent in diabetic patients with carotid atherosclerosis with the CARDS trial showing a 37% reduction in cardiovascular ischemic events and a 48% reduction in ischemic stroke by treatment with atorvastatin. Statins therapy has been shown to reduce carotid plaque progression especially as high-intensity statins are more likely to do so compared to low-intensity statins. For patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease, current guidelines recommend use of high-intensity statins, if the patients are 75 years or younger and at least moderate-intensity statins if they are older regardless of baseline lipid levels. Table 1 shows examples of low-, moderate-, and high-intensity statins with dosages.

Angiotensin Convertase Enzyme Inhibitor (ACEI) and Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (ARB)

Several trials have shown the potential for ACEI and ARBs in primary stroke reduction irrespective of their blood pressure–lowering effect. In the HOPE trial, ramipril significantly lowered ischemic stroke, cardiovascular events, and death in high-risk cardiovascular patients. The LIFE trial showed that Losartan (ARB) significantly reduced cardiovascular events beyond its role in blood pressure lowering. The SCOPE trial again showed that Candesartan (ARB) significantly reduced nonfatal strokes beyond effects of blood pressure lowering in the elderly population with isolated systolic hypertension. In the MOSES trial when ARBs were compared to calcium channel blockers, there was significant reduction in cardiovascular events especially ischemic stroke although both drugs equally lowered blood pressure. The hypothesis is that AT2 receptor stimulation by these agents cause stroke reduction as these agents provide protection against cardiovascular damage and tissue regeneration. Head-to-head trials comparing ARB and ACEI, such as the ONTARGET trial, showed a 9% greater reduction in primary stroke in patients on ARBs compared to those on ACEIs. A meta-analysis comparing ACEIs and ARBs from six randomized control trials showed that ARBs are even superior to ACEIs in stroke reduction. Patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis should take either an ACEI or an ARB, especially if they have hypertension.

Management of Important Risk Factors

Hypertension

Hypertension is one of the most important risk factors for stroke. Multiple studies have shown linear relationship between increasing blood pressures and risk of stroke. Studies have shown decreasing blood pressure by 10 mm Hg can decrease stroke incidence up to 33%. A meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials showed a 24% reduction in stroke with use of an antihypertensive. Also studies like systolic hypertension in elderly program (SHEP) and Framingham heart study (FHS) showed that blood pressure is directly related to the progression of carotid stenosis as well. Controlling blood pressure is a crucial component of medical management of carotid stenosis. Guidelines recommend a target blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg. This may not apply to patients during the acute phase of TIA or stroke who need higher pressures. Although the primary goal is to reduce blood pressure, ACEI/ARB with or without diuretics should be considered as first line agents, if possible. In the PROGRESS trial, patients with ischemic stroke who received a combination of perindopril (ACEI) and indapamide (diuretic) showed a 28% risk reduction in recurrent ischemic events.

Diabetes

The risk of ischemic stroke is increased two- to fivefold among patients with diabetes compared to those without diabetes. Carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) was also noted to progress quicker in patients with diabetes. Current guidelines recommend treating diabetes with a hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) target less than 7%. All patients with diabetes should receive education on exercise, diet, and glucose-lowering medications. All patients with diabetes and carotid atherosclerosis should be treated with a statin regardless of baseline lipid levels as the CARDS trial has shown to reduce overall cardiovascular risk by 37% and stroke risk by 48% by using atorvastatin in these patients even with normal lipid levels.

Hyperlipidemia

Increased risk of stroke is only mildly associated with hyperlipidemia in various clinical trials. However, reduction in LDL level with statin therapy regardless of baseline LDL levels has shown to significantly decrease the incidence of stroke. Details of the benefits of statin therapy have been discussed more in detail above under the section of medications. In patients who do not tolerate statins, other options like bile acid sequestrants or ezetimibe could be considered, but with caution and only in consultation with a preventive vascular medicine specialist as benefits from nonstatin antihyperlipidemic agents is not well established. Previous guidelines recommended treating target LDL levels; however, this is no longer recommended, and statins are recommended for all patients with clinical atherosclerotic vascular disease with far majority being treated with moderate-to-high intensity statins.

Smoking

Smoking has been well recognized as a risk factor for ischemic stroke. Smoking increases the risk of ischemic stroke by 25% to 50%. Quitting smoking decreases risk of ischemic stroke significantly within 5 years of quitting compared to those who continue smoking. Heavy smokers are noted to have a higher stroke rate compared to light smokers. Increased duration and amount of smoking also has been directly related to high-grade carotid stenosis. Hence, smoking cessation is strongly recommended to all patients with carotid artery disease.

Current clinical guidelines recommend that at every visit, the vascular physicians should ask his or her patients about history of smoking and their current smoking status. In addition, smokers should be assisted with counseling and developing a plan for quitting that may include pharmacotherapy and/or referral to a smoking cessation program. In the absence of contraindications, pharmacologic therapies are strongly recommended.

Pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation include the following:

1. Varenicline (Chantix): It is a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist and has thus far demonstrated higher efficacy of smoking cessation compared to available alternatives. In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial comparing varenicline with bupropion, varenicline produced the highest rates of abstinence at 1 year after treatment.

2. Bupropion: It is an aminoketone antidepressant agent that has a weak inhibitory effect on norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake. In randomized placebo-controlled trials, sustained release bupropion at doses of 150 and 300 mg daily resulted in significant abstinence rates compared to placebo.

3. Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT): NRTs aid in smoking cessation by reducing the urge to smoke and other withdrawal symptoms. Currently, there are multiple routes of NRT administration, which includes transdermal patches, gums, inhalers, sublingual tablets, and lozenges. There is currently no scientific evidence favoring one form of NRT over other, and it is possible that one form of NRT may be more effective in an individual than another form. In fact, combining two different forms of NRT, such as nicotine patches with a fast-acting form such as nicotine gum or inhalers, has shown to be more effective than nicotine patches alone.