Benign Lymph Node Disease Involving the Mediastinum

Jemi Olak

Mediastinal lymphadenopathy is most commonly seen within the middle (visceral) compartment of the mediastinum. It occurs most often in the right lower paratracheal, subcarinal, and aortopulmonary window regions. It is seen less often in the anterior and posterior mediastinal compartments. While mediastinal lymphadenopathy is more commonly associated with malignancy, many benign diseases can cause enlargement of mediastinal lymph nodes and these diseases are the focus of this chapter.

Benign causes of mediastinal lymphadenopathy are listed in Table 189-1.

Mediastinal Granulomatous Disease

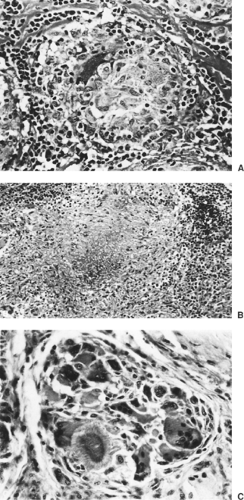

Granulomatous disease is the most common benign cause of mediastinal lymphadenopathy. According to Dines and associates,5 approximately 40% of patients with mediastinal granulomas are asymptomatic. According to Ioachim,13 they are the result of a specialized immune reaction to insoluble or particulate substances. Generally, granulomas are classified either as necrotizing, nonnecrotizing, or foreign body, as illustrated in Figure 189-1.

Transtracheal and transbronchial fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy are two techniques that have been used to evaluate enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes. In 1994, Wiersema and associates29 described the use of esophageal ultrasound–directed FNA of mediastinal lymph nodes to assist in the determination of the etiology of mediastinal lymphadenopathy. This technique is particularly useful for nodes in the subcarinal and aortopulmonary window locations. More recently, Silvestri and others have reported on the technique of endobronchial ultrasound–guided FNA (EBUS-FNA) of lymph nodes in the right lower paratracheal, subcarinal, and aortopulmonary window and even in proximal hilar locations; this has been a useful addition to the diagnostic armamentarium. Cervical mediastinoscopy and anterior mediastinotomy, however, remain the procedures of choice when material is required for histologic examination. All of these procedures are routinely accomplished in an outpatient setting.

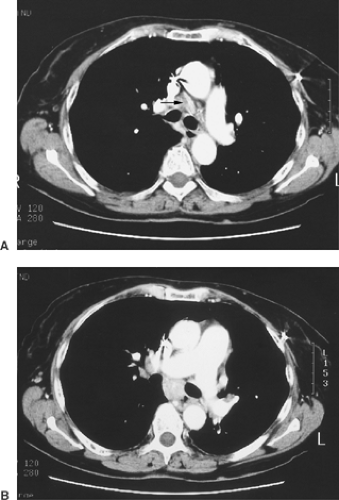

Radiographically, granulomas are solid lesions, as illustrated in Figure 189-2. Slightly less than half contain calcium. In addition, areas of necrosis may be evident within a granuloma.

When a lymph node that is suspected of harboring granulomatous disease is biopsied, stains for microoganisms should be performed and a portion of the material biopsied should be sent for mycobacterial and fungal culture. In addition, consideration should be given to an examination of the biopsy material with polarized light, especially if a history of silica exposure has been obtained.

Tuberculosis

In immunocompetent adults as opposed to children with primary infection due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB), mediastinal lymphadenopathy is a relatively uncommon finding. It is seen more often, however, in immunocompromised adult hosts. The overall decline in the incidence of tuberculosis in the United States was reversed in the mid-1980s as a result of the AIDS epidemic. Selwyn and associates26 report that AIDS patients have a 7% annual risk of tuberculosis reactivation compared with a 3% to 6% lifetime risk for non-AIDS patients. Pitchenick and Rubinson20 report that 59% of their AIDS patients who developed TB had mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy. This finding was corroborated by Hamarati and associates,11 who reported that among 98 patients with cultures positive for M. tuberculosis, 60% of the HIV-positive patients had mediastinal lymphadenopathy on chest x-ray, compared with 23% of the HIV-negative patients.

Tuberculous granulomas share many features with granulomas secondary to fungal disease. They may be distinguished from other granulomas by staining positive for acid-fast bacilli. In addition, tuberculous granulomas typically feature caseating (coagulative) necrosis. In acute tuberculous lesions, suppuration is a common finding whereas later on, Langhans-type giant cells and caseating necrosis may be predominant features. In older lesions, fibrosis or calcification may be present.

Fungal Infection

At present, the most common cause of mediastinal granuloma in adults is fungal infection. In order of decreasing frequency, the organisms responsible are Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidiodes immitis, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Blastomyces dermatitidis.

Table 189-1 Benign Mediastinal Lymphadenopathies | ||

|---|---|---|

|

H. capsulatum is an organism endemic to the eastern and central river valleys of the United States. Edwards and associates7 have estimated that more than 80% of the population in these regions is sensitized to the fungus and that approximately 22% of the U.S. population has been infected by it. Medical therapy with amphotericin or ketoconazole is reserved for patients with acute infection. According to Dines and associates,5 fibrosing mediastinitis is a well-documented sequela of exposure to H. capsulatum. It developed in 11 of 31 (34%) patients with mediastinal granuloma seen at the Mayo Clinic within 2 years of documented exposure. Mole and associates17 have reported its occurrence following infection with Aspergillus, Mucor, Cryptococcus, Blastomyces, and Mycobacterium. Autoimmune disease and sarcoidosis have also been known to result in fibrosing mediastinitis. Fibrosing mediastinitis is felt to result from a delayed hypersensitivity reaction that causes intense inflammation rather than an active fungal proliferation. Mathisen and Grillo16 recommend that consideration be given to surgical intervention for patients with large mediastinal granulomas, whether or not they are symptomatic, to avoid the complications associated with the development of fibrosing mediastinitis.

Fibrosing mediastinitis is the most common benign cause of superior vena cava (SVC) obstruction. It may also result in airway stenosis, esophageal stenosis, or the development of esophagorespiratory fistulas. When infection with H. capsulatum reaches this stage, it can have life-threatening implications for which no medical therapy is effective and surgical therapy is only palliative. Because carinal pneumonectomy is associated with a high mortality rate (10%–15%), esophageal and respiratory stents might be considered to palliate selected patients with stenosis even though their use for this indication remains investigational. SVC obstruction has been treated by Doty6 with spiral vein bypass with acceptable results. Mathisen and Grillo16 have recommended treatment of esophagorespiratory fistulas by separation of the esophagus from the tracheobronchial tree and closure of each defect in two layers buttressed by a well-vascularized (e.g., intercostal or serratus anterior) muscle flap. In selected cases, this condition may also be treated with a covered esophageal stent. A subacute form of disease has been described by Urschel and associates.28 It occurred in six patients

known to have had a history of H. capsulatum infection. The subacute form was diagnosed based upon rising Histoplasma complement fixation titers and was successfully controlled with oral ketoconazole.

known to have had a history of H. capsulatum infection. The subacute form was diagnosed based upon rising Histoplasma complement fixation titers and was successfully controlled with oral ketoconazole.

Figure 189-2. CT scans demonstrating mediastinal lymphadenopathy secondary to granulomatous disease. A: Precarinal mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The lymph node measures 2.5 cm in short-axis diameter. B: Subcarinal mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The lymph node measures 2 cm in short-axis diameter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|