CHAPTER 10 Benign Lesions of the Lung

DEFINITION AND INCIDENCE

Benign lesions of the lung are quite rare. In one of the largest series reported, Martini and colleagues observed that less than 1% of lung lesions resected at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center were benign. A benign lung nodule is difficult to define and classify because some lesions that are called “benign” have malignant properties. However, the best definition of a benign lesion is one in the pulmonary parenchyma that does not metastasize and does not penetrate through surrounding tissue planes. When it is completely resected, a benign tumor should not recur.1

The controversy arises because some tumors are often labeled benign (such as pulmonary blastomas) but have the potential to exhibit malignant properties, and thus clear-cut boundaries between malignant and benign often are blurred. Benign tumors of the lung can arise from all of the various cell types that are present in the lung. Box 10-1 lists the most common benign tumors based on their cells of origin.

Box 10–1 Common Benign Tumors of the Lung Based on Cells of origin

EVALUATION FOR AN INDETERMINATE PULMONARY NODULE

The single most important test for a patient who arrives at the office with an indeterminate pulmonary nodule is the review of old chest radiographs and computed tomographic (CT) scans. The radiograph should be interpreted in the context of the patient’s medical history. Important factors include a history of a previous solid organ cancer and history of smoking. The physical examination is typically unremarkable, without any cervical lymphadenopathy. If the nodule is new or if the patient did not have a previous chest radiograph, chest computed tomography with contrast enhancement and integrated positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET/CT) are performed. If the nodule lacks calcification on the chest CT scan, it is indeterminate.2,3

Positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) and integrated PET/CT scanning have recently become important adjuncts in the armamentarium of general thoracic surgeons. PET/CT has helped physicians investigate an indeterminate pulmonary nodule that is larger than 5 mm (smaller nodules that are malignant can be missed by PET/CT). If the nodule has glucose avidity and a maximum standard unit value (maxSUV) of 2.5 or greater, it has a significant chance (above 90% in our series) of being malignant.4 In a study by Bryant and Cerfolio5 of 585 patients, 496 patients had a malignant nodule, and their median maxSUV was 8.5. Eighty-nine patients had a benign nodule, and the median maxSUV was 4.9 (P < .001). They observed that if the maxSUV was between 0 and 2.5, the chance that the nodule was malignant was 24%; between 2.6 and 4.0, it was 80%; and for 4.1 or greater, it was 96%. False-negative results occurred from bronchoalveolar carcinoma in 11 patients, carcinoid in 4, and renal cell in 2. False-positives included fungal infections in 16 patients.5 Similarly, enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes with a maxSUV of greater than 2.5 are likely to be malignant (we have shown that a lymph node with a maxSUV of 5.3 or greater has a 92% chance of being malignant).6 Patients with lymphadenopathy on CT scans or uptake on PET/CT scans should have mediastinoscopy, endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration, or endoscopic bronchial ultrasound examination to obtain tissue diagnosis before a thoracotomy. If the CT and FDG-PET scans are equivocal or abnormal, resection is usually best in patients who are good candidates for surgery.

In this chapter, we discuss the most common benign tumors of the lung (adenomas and hamartomas constitute the largest group of benign lung tumors) and highlight the important clinical factors associated with each one. Each section is organized in the following fashion to help the reader find the pertinent points he or she is looking for: definition, incidence, special history or physical examination findings, unique radiologic characteristics, intraoperative tips for resection if indicated, pathologic characteristics, and special postoperative care or follow-up care including the risk of recurrence. Box 10-2 lists the radiographic characteristics typical of benign lesions.

Box 10–2 Radiographic Characteristics of Benign Nodules31,32

HAMARTOMA

Hamartomas are the most common benign lung lesions and account for more than 70% of all nonmalignant tumors of the lung.7 They are mesenchymal tumors with a peak incidence in the sixth decade of life, and approximately 90% are asymptomatic. Men are affected twice as often as women are. Ninety percent of these tumors present as solitary peripheral nodules and account for about 4% of all solitary pulmonary nodules (Fig. 10-1). The 8% to 10% of hamartomas that have presenting symptoms such as cough, hemoptysis, and recurrent pulmonary infections are usually endobronchial lesions. Resection of these is usually needed even when a definitive biopsy has been performed on them and they are proven to be benign because they cause local problems from airway obstruction. These problems include recurrent pneumonia, parapneumonic empyema, hemoptysis, and cough. Laser ablation can be used to help open the airway, but complete resection is preferred.

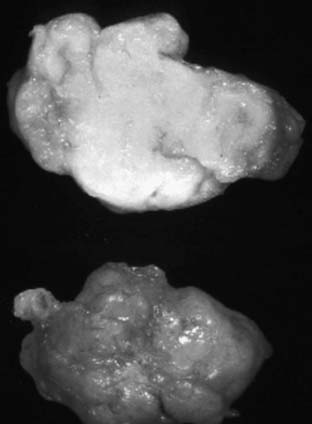

Cartilage is present in most lesions and is diagnostic of a hamartoma. There are usually nests of cartilage surrounded by cellular fibrotic tissue. Mature fat cells are a frequent component, and their presence on CT scan (low Hounsfield units) is strong evidence for the diagnosis of a hamartoma.8 Rarely, bone, vessels, bronchioles, and smooth muscle are found. On gross examination, the bosselated appearance is typical for a hamartoma. The usual size is 1 to 3 cm, with the lesion being round and firm. They are easily shelled out from the surrounding lung tissue (Fig. 10-2). As with any indeterminate pulmonary nodule, lung-preserving techniques are best if possible.

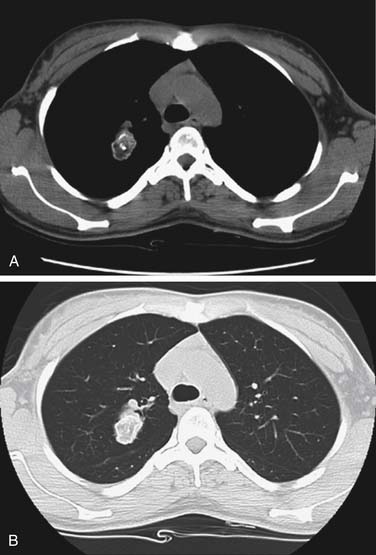

On radiographic examination, as shown in Figure 10-3, hamartomas are peripheral lesions that are most often located in the lower lung fields and are well circumscribed. The majority are less than 4 cm in diameter, and calcifications can be appreciated on radiographs in 10% to 30% of cases (Fig. 10-4). Calcifications are described as being “popcorn”-like or diffuse. Hamartomas display a slow growth rate (~3 mm/year) and are rarely multiple. Although it is identifiable in only half of the cases, fat density as identified by CT scan (low Hounsfield units) is strongly suggestive of a benign hamartoma.9,10 Endobronchial lesions are not identifiable with radiographic examination unless distal parenchymal changes have occurred (e.g., pneumonia or atelectasis).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree