INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Although the indications for an antireflux repair and the biomechanics of an antireflux repair done by laparoscopic and open approaches are similar, there are some specific situations in which a transthoracic Belsey Mark IV fundoplication or a transthoracic Nissen fundoplication provides an advantage. These include the following.

A repeat open transthoracic operation can be technically easier in a patient with intrathoracic stomach and a history of multiple failed antireflux repairs.

A repeat open transthoracic operation can be technically easier in a patient with intrathoracic stomach and a history of multiple failed antireflux repairs.

A transthoracic fundoplication is a particularly useful approach in patients who require fundoplication but have a “hostile” abdomen due to multiple previous surgeries. It is also of use in patients who have had multiple transabdominal antireflux procedures.

A transthoracic fundoplication is a particularly useful approach in patients who require fundoplication but have a “hostile” abdomen due to multiple previous surgeries. It is also of use in patients who have had multiple transabdominal antireflux procedures.

A transthoracic approach is useful when a partial fundoplication is planned after a transthoracic myotomy for motility disorders such as diffuse esophageal spasm or pulsion diverticula.

A transthoracic approach is useful when a partial fundoplication is planned after a transthoracic myotomy for motility disorders such as diffuse esophageal spasm or pulsion diverticula.

A transthoracic approach is useful for a patient who has extensive shortening of the esophagus. In this situation, the thoracic approach allows for maximum mobilization of the esophagus in order to place the repair, without tension, in the abdomen with or without a gastroplasty to lengthen the esophagus.

A transthoracic approach is useful for a patient who has extensive shortening of the esophagus. In this situation, the thoracic approach allows for maximum mobilization of the esophagus in order to place the repair, without tension, in the abdomen with or without a gastroplasty to lengthen the esophagus.

A transthoracic approach is useful for a patient with reflux disease who requires a thoracotomy for another reason, such as pulmonary disease. If the pulmonary disease is on the left side, an open transthoracic approach allows both problems to be addressed through one incision.

A transthoracic approach is useful for a patient with reflux disease who requires a thoracotomy for another reason, such as pulmonary disease. If the pulmonary disease is on the left side, an open transthoracic approach allows both problems to be addressed through one incision.

The propulsive power of the esophageal body should exceed the resistance to flow through the antireflux repair.9,10 Consequently, the choice between a 360-degree fundoplication (Nissen) or partial 240-degree fundoplication (Belsey) is influenced by the strength of the peristaltic contractions. An esophageal body that has normal wave progression and good contraction amplitude will do well with a complete 360-degree fundoplication. When the prevalence of peristaltic wave progression is reduced to <50% or esophageal contraction amplitudes in the distal half of the esophagus are ≤20 mm Hg, a partial 270-degree fundoplication is recommended as this degree of fundoplication has no measurable resistance to esophageal emptying. Inappropriate matching of the body of the esophagus to the resistance imposed by the antireflux procedure can cause a delay in the passage of food through the repair and symptoms of dysphagia. To avoid excessive outflow resistance, the antireflux repair should be performed in such a manner that the postoperative sphincter pressure is not in the hypertensive range and the length of the sphincter measures 3 to 4 cm.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

The identification of a patient for an antireflux surgery includes both a complete clinical evaluation consisting of a history, physical examination, and an upper gastrointestinal barium contrast video, and an objective evaluation consisting of an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, esophageal manometry, and pH testing. If the patient requires a redo antireflux procedure, a more thorough and comprehensive evaluation is done. This requires determining the indication for the initial antireflux surgery, reviewing the patient’s clinical history prior to and after the operation, and thoroughly studying the operative report. A specific note should be made of the location of the gastroesophageal junction in relation to the location of the fundoplication. The surgeon should also determine if the fat pad was dissected, if the vagi were preserved, and if the crura were closed. The technical details of the construction of the fundoplication itself should be noted. With this information in mind, an endoscopy, upper gastrointestinal barium contrast video, esophageal manometry, pH testing, and a gastric emptying study should be done. Patients who will undergo a transthoracic fundoplication, should also have an assessment of their ability to tolerate a thoracotomy and single-lung anesthesia.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Initial Steps and Thoracotomy

The Belsey operation requires approximately 4 cm of tension-free intra-abdominal esophagus. Consequently, the clinical success of a Belsey repair decreases progressively from 90% in patients who have no esophageal shortening to 50% in those who have significant shortening and a repair under tension. In those patients with shortening, a Collis gastroplasty is added to the repair to gain additional length and alleviate any tension on the repair. A step-by-step description of the Belsey antireflux procedure is detailed below.9,10,11

An epidural catheter is placed to optimize the patient’s postoperative pain control.

An epidural catheter is placed to optimize the patient’s postoperative pain control.

The patient is intubated with a double-lumen endotracheal tube for anesthesia in the operating room with precautions taken to avoid aspiration. The position of the tube is verified by bronchoscopy. The left lung is selectively deflated. Adequate venous access, a Foley catheter, and an arterial line are placed. An on-table endoscopy is then performed if the surgeon did not perform an endoscopy prior to the surgery to evaluate the hiatal hernia and exclude the existence of Barrett’s esophagus, neoplasm, a stricture, or any other complications of reflux disease.

The patient is intubated with a double-lumen endotracheal tube for anesthesia in the operating room with precautions taken to avoid aspiration. The position of the tube is verified by bronchoscopy. The left lung is selectively deflated. Adequate venous access, a Foley catheter, and an arterial line are placed. An on-table endoscopy is then performed if the surgeon did not perform an endoscopy prior to the surgery to evaluate the hiatal hernia and exclude the existence of Barrett’s esophagus, neoplasm, a stricture, or any other complications of reflux disease.

Patient is placed in a right lateral decubitus position, the usual position for left posterior thoracotomy. The pressure points are padded, and pillow is placed between the lower extremities. A sequential compression device is also placed for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis.

Patient is placed in a right lateral decubitus position, the usual position for left posterior thoracotomy. The pressure points are padded, and pillow is placed between the lower extremities. A sequential compression device is also placed for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis.

The table is flexed above the hip, and the patient is secured to the table with a belt.

The table is flexed above the hip, and the patient is secured to the table with a belt.

The diaphragmatic hiatus is approached through a left posterolateral thoracotomy in the sixth intercostal space (i.e., along the upper border of the seventh rib).

The diaphragmatic hiatus is approached through a left posterolateral thoracotomy in the sixth intercostal space (i.e., along the upper border of the seventh rib).

For patients who had a previous failed antireflux repair, we prefer to use the seventh intercostal space. This allows better exposure of the abdomen through a peripheral diaphragmatic incision.

For patients who had a previous failed antireflux repair, we prefer to use the seventh intercostal space. This allows better exposure of the abdomen through a peripheral diaphragmatic incision.

The incision is made circumferentially in the anterolateral portion of the diaphragm, 2 to 3 cm from the chest wall, for a distance of 10 to 15 cm.

The incision is made circumferentially in the anterolateral portion of the diaphragm, 2 to 3 cm from the chest wall, for a distance of 10 to 15 cm.

A sufficient fringe of diaphragm must be left along the chest wall to allow for easy closure of the diaphragmatic incision.

A sufficient fringe of diaphragm must be left along the chest wall to allow for easy closure of the diaphragmatic incision.

If further abdominal exposure is necessary, the thoracic incision can be extended across the costal margin and diagonally down to the abdominal midline, dividing the fibers of the left rectus abdominis muscle.

If further abdominal exposure is necessary, the thoracic incision can be extended across the costal margin and diagonally down to the abdominal midline, dividing the fibers of the left rectus abdominis muscle.

Esophageal Mobilization

The esophagus is mobilized from the diaphragm to underneath the aortic arch. Care is taken not to injure the vagal nerves. Branches of the vagal plexus going to the left and right lung must be divided to obtain maximal esophageal length. This allows construction, without tension, of a partial fundoplication over a 4-cm segment of abdominal esophagus. Two vessels arise from the proximal descending thoracic aorta just distal to the arch and pass over the esophagus to the left main stem bronchus. They are the left superior and inferior bronchial arteries. Ligation of these arteries is also necessary to fully mobilize the esophagus. In addition to these arteries, two to three direct esophageal branches come off the distal descending thoracic aorta and pass directly to the esophagus. These are also ligated and divided without concern about ischemic necrosis of the esophagus. There is sufficient blood supply to maintain the integrity of the esophagus through its intrinsic arterial plexus, fed by the inferior thyroid artery in the neck and by branches from the right bronchial artery in the thorax. This degree of mobilization is necessary to place the repair into the abdomen without undue tension. Failure of adequate mobilization is one of the major causes for subsequent breakdown of a repair and the return of symptoms. Therefore, if after adequate mobilization, there is insufficient intra-abdominal length or any tension, a Collis gastroplasty should be added to the repair.

Mobilization of the Gastroesophageal Junction and Cardia

Freeing the gastroesophageal junction and gastric cardia from the diaphragmatic hiatus is the most difficult portion of the procedure, but can usually be completed through the esophageal hiatus. It is unnecessary to make a counter incision through the central tendon of the diaphragm or to enlarge the hiatus by an incision through the crura. When there is no hiatal hernia, the rim of the hiatus is grasped with an Allis clamp, and the dissection is started by gaining access to the abdominal cavity with the division of the phrenoesophageal membrane. It can be difficult at times to find the correct tissue plane once the membrane has been divided due to the protrusion of the preperitoneal fat. Persistence and dissection underneath the retracted left crus, away from the gastric vessels, eventually yields entry into the free peritoneal space. Entering the abdominal cavity is easier when a hiatal hernia is present. When a hiatal hernia is present, the hernia sac can be entered near the hiatus. It is again important to be careful to preserve the vagus nerve during the dissection of the sac. In moderate to large hernia, the sac is excised.

The proper stance of the surgeon at the operating table aids in freeing the hiatus. With the patient in the left posterior thoracotomy position, the surgeon should stand adjacent to the patient’s back, facing the head of the table. The left index and middle fingers are placed through the diaphragmatic hiatus into the abdominal cavity, with the palm facing the patient’s feet. The surgeon’s line of vision is down and backward under his or her left axilla. With judicious use of the left thumb, index and middle fingers, the surgeon is able to spread the hiatal tissues and divide them with a scissors controlled by the right hand. In this position, the left hand is also used to retract the esophagus and protect the vagal trunks. Although it sounds somewhat awkward, this stance greatly facilitates the most difficult part of the operation.

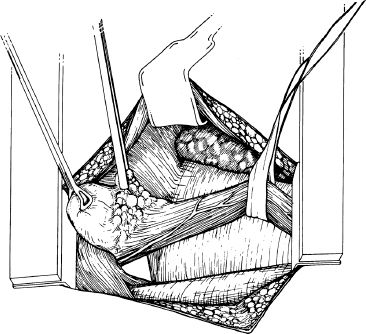

All the attachments between the gastric cardia and diaphragmatic hiatus are divided. An inconstant artery (Belsey’s Artery) communicating between the left gastric and the inferior phrenic artery should be divided. This is encountered in the posteromedial dissection, and it is important to control this vessel before division. The short gastric vessels are divided and ligated one by one to allow good mobilization of the fundus. When free, the fundus and part of the body of the stomach are drawn up through the hiatus into the chest (Fig. 5.1). The vascular fat pad, which lies on the anterior and lesser curvature surface of the cardia, is dissected. Care must be taken during this dissection to avoid injury to the vagal nerves. The fundus of the stomach must adhere firmly to the lower esophagus and the dissection of the fat pad facilitates this.

The completely mobilized esophagus is encircled with a Penrose drain and retracted toward the anterior border of the hiatus to give exposure for closure of the posterior hiatus. The right and left crura of the diaphragmatic hiatus are identified and approximated with interrupted figure-eight nonabsorbable 0 sutures (Ethibond), taking generous bites of muscle. Usually there is a decussation of muscle fibers from the right crus that passes anteriorly over the aorta to join muscle fibers from the left crus, but occasionally the aorta lies free within the enlarged hiatus. In either situation, the first crural suture is placed close to the aorta. Traction on this first posterior crural stitch elevates the right crus toward the surgeon and facilitates the placement of subsequent crural sutures. Occasionally, it is necessary to mobilize the pericardium off the diaphragm to give better exposure of the fascia and muscle making up the right crus. The subsequent crural sutures should incorporate the fascia from the periphery of the central tendon that blends in with the muscle fibers making up the right crus.

Figure 5.1 Mobilization of the esophagus and stomach through a left posterolateral thoracotomy. The esophagus, gastroesophageal fat pad, stomach, diaphragmatic hiatus, aorta, pericardium, and lung are depicted. The fundus of the stomach is drawn through the hiatus into the chest with a Babcock clamp. The forceps is on the fat pad at the gastroesophageal junction, which is then dissected.