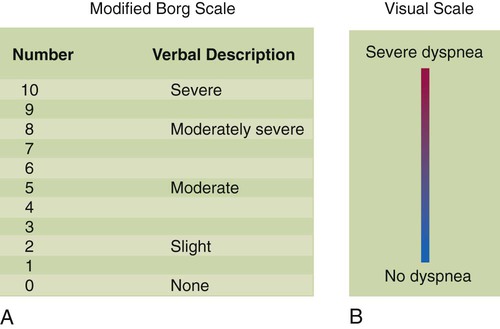

After reading this chapter you will be able to: 1. To establish a rapport between the clinician and patient 2. To obtain essential diagnostic information 3. To help monitor changes in the patient’s symptoms and response to therapy For these reasons, interviewing is a crucial aspect of general patient assessment. • Sensory and emotional factors • Verbal and nonverbal components of the communication process • Cultural and other internal values, beliefs, feelings, habits, and preoccupations of both the health care professional and the patient Because of the above-listed factors, no two interviews are the same. The ideal interview is one in which the patient feels secure and free to talk about important personal matters. Each interview should begin with the RT introducing himself or herself to the patient and stating the purpose of the visit. The introduction is done in the social space, approximately 4 to 12 feet from the patient. It begins the process of establishing a rapport with the patient and helps the patient feel more comfortable about answering personal questions. Pulling the curtain between the beds of a semiprivate room also may be helpful in making the patient feel more at ease with the interview (Box 15-1). Using neutral questions and avoiding leading questions during the interview is important. Asking the patient, “Is your breathing better now?” leads the patient toward a desired response and may elicit false information. Asking the patient, “How is your breathing now?” is a better way to get accurate information about the patient’s breathing (Box 15-2). • How severe is it? (This can be rated on a scale of 1 to 10.) • Where on the body is it? (This is especially important for chest pain.) • What seems to make it better or worse? 1. The neural drive to breathe 2. The tension developed in the respiratory muscles 3. The corresponding displacement of the lungs and chest wall 1. The RT should ask what activities of daily living tend to trigger episodes of dyspnea. For example, is dyspnea triggered by walking on flat surfaces, by climbing stairs, by bathing, by dressing? 2. The RT should ask how much exertion is required for the patient to stop to catch his or her breath with different activities. Does the patient need to stop after walking up one flight of stairs or one step? Dyspnea provoked by less strenuous activities indicates more advanced disease. 3. The RT should ask whether the quality or the sensation of breathing discomfort varies with different activities. 4. To gain a better understanding of the patient’s history, the RT should ask the patient to recall when dyspnea first began and how it has evolved over time. Has dyspnea progressed slowly or rapidly? How long has this progression taken place: over a period of months or years? Has there been a dramatic change in the intensity of dyspnea over recent months, weeks, days, or even within the past few hours? The intensity of dyspnea can be documented using a numeric intensity or visual analog scale (Figure 15-1). Such scales provide a way to evaluate the patient’s response to treatment over time. These scales are important because objective lung function measurements (e.g., pulmonary function tests, PaO2) seldom correlate with the degree of dyspnea in many patients. Important characteristics of the patient’s cough to identify include whether it is dry or loose, productive or nonproductive, and acute or chronic and whether it occurs more frequently at particular times (i.e., day or night). Knowledge of such details may help in determining the cause of the cough. A dry, nonproductive cough is typical for restrictive lung diseases such as CHF or pulmonary fibrosis. A loose, productive cough is more often associated with inflammatory obstructive diseases such as bronchitis and asthma. The most common cause of an acute, self-limited cough is a viral infection of the upper airway. Common causes of chronic coughing include asthma, postnasal drip, chronic bronchitis, and gastroesophageal reflux,1 although combinations of these often exist.2 Cough is also associated with the use of certain medications for hypertension (e.g., angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors).3 It was believed for many years that there was a link between fever and atelectasis in postoperative surgical patients. However, more recent evidence has shown no link between the formation of atelectasis and the development of fever (>101.3° F [>38.5° C]) during the first 72 hours after surgery.4

Bedside Assessment of the Patient

Describe why patient interviews are necessary and the appropriate techniques for conducting an interview.

Describe why patient interviews are necessary and the appropriate techniques for conducting an interview.

Identify abnormalities in lung function associated with common pulmonary symptoms.

Identify abnormalities in lung function associated with common pulmonary symptoms.

Identify breathing patterns associated with underlying pulmonary disease.

Identify breathing patterns associated with underlying pulmonary disease.

Differentiate between dyspnea and breathlessness.

Differentiate between dyspnea and breathlessness.

Identify terms used to describe normal and abnormal lung sounds.

Identify terms used to describe normal and abnormal lung sounds.

Describe the mechanisms responsible for normal and abnormal lung sounds.

Describe the mechanisms responsible for normal and abnormal lung sounds.

Explain why it is necessary to examine the precordium, abdomen, and extremities in patients with cardiopulmonary disease.

Explain why it is necessary to examine the precordium, abdomen, and extremities in patients with cardiopulmonary disease.

Describe some common abnormalities found during the examination of the precordium, abdomen, and extremities in patients with cardiopulmonary disease.

Describe some common abnormalities found during the examination of the precordium, abdomen, and extremities in patients with cardiopulmonary disease.

Interviewing the Patient and Taking a Medical History

Principles of Interviewing

Structure and Technique for Interviewing

Common Cardiopulmonary Symptoms

Dyspnea

Assessing Dyspnea in the Interview

Cough

Fever

Bedside Assessment of the Patient