Bacterial Infections of the Lungs and Bronchial Compressive Disorders

Joseph I. Miller Jr.

Suppurative diseases of the lung and certain bronchial compressive disorders formed the basis for the development of thoracic surgery as a separate surgical specialty. Despite the development of antibiotics and newer techniques in diagnosis and management, these disorders continue to form an important part of the specialty of general thoracic surgery. As noted by Hood,19 a number of factors contribute to the continued frequency with which these disease entities are seen. These include the emergence of antibiotic-resistant organisms, increased numbers of immunosuppressed individuals, increased drug abuse, an increasing older population, and the emergence of nosocomial pulmonary infections.

The prevalence of these conditions requires that the thoracic surgeon have knowledge and surgical skills to handle these disease entities. An outline of the surgical spectrum of bacterial infections and bronchocompressive disorders of the lung is given in Table 89-1.

Bronchiectasis

The term bronchiectasis is derived from the Greek bronchus and ektasis, meaning dilatation. In essence, as pointed out by Hodder and colleagues,18 the term refers to the abnormal permanent dilatation of subsegmental airways. The history of bronchiectasis parallels that of thoracic surgery and has been outlined previously by Lindskog.23 The techniques of segmental resection were developed in large part because of this entity. Detailed anatomic descriptions of segmental anatomy by Boyden7 led to the development of individual ligation of the hilar bronchovascular structures and significantly decreased postoperative complications. With the development of antibiotics in the 1940s, this entity has not been seen as frequently; but with the emergence of drug-resistant microorganisms and increasing frequency of drug-resistant tuberculosis, an increased incidence of postinfectious bronchiectasis is being noted.

An outline of the etiology of bronchiectasis is given in Table 89-2. Etiologic conditions can be divided into congenital and acquired. The most frequent congenital causes are cystic fibrosis, hypogammaglobulinemia, and Kartagener’s syndrome. The most frequent acquired cause is secondary to an infectious process.

Barker5 emphasized that the pathophysiology of bronchiectasis requires an infectious process plus impairment of bronchial drainage, airway obstruction, or a defect in host defense. Bronchial obstruction can be caused by foreign body aspiration or enlarged lymph nodes compressing a bronchus, as seen in middle lobe syndrome. Barker5 noted that in immunocompromised patients, there may be ciliary dyskinesia, airway immune effector cells, neutrophilic proteases, and inflammatory cytokines. Regardless of the cause, an intense inflammation results in transmural inflammation, mucosal edema, and bronchial neovascularization.

The terms cylindrical, varicose, and saccular have been used to describe the pathology of bronchiectasis. A classification of

bronchiectasis is given in Table 89-3. Saccular bronchiectasis follows a major pulmonary infection or results from a foreign body or bronchial stricture and is the principal type of surgical importance. Cylindrical bronchiectasis consists of bronchi that do not end blindly but communicate with lung parenchyma. This is frequently associated with tuberculosis and immune disorders. Hood20 noted a third type referred to as varicose, a mixture of the former two, distinguished by alternating areas of cylindrical and saccular disease. Pseudobronchiectasis, a term first reported by Blades and Dugan,6 is a cylindrical dilatation of a bronchus after an acute pneumonic process that is temporary and disappears in several weeks or months. This type has no surgical implications. In addition, certain genetic syndromes may be associated with some form of bronchiectasis. These include cystic fibrosis, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, and immunoglobulin A (IgA) and IgG deficiency.

bronchiectasis is given in Table 89-3. Saccular bronchiectasis follows a major pulmonary infection or results from a foreign body or bronchial stricture and is the principal type of surgical importance. Cylindrical bronchiectasis consists of bronchi that do not end blindly but communicate with lung parenchyma. This is frequently associated with tuberculosis and immune disorders. Hood20 noted a third type referred to as varicose, a mixture of the former two, distinguished by alternating areas of cylindrical and saccular disease. Pseudobronchiectasis, a term first reported by Blades and Dugan,6 is a cylindrical dilatation of a bronchus after an acute pneumonic process that is temporary and disappears in several weeks or months. This type has no surgical implications. In addition, certain genetic syndromes may be associated with some form of bronchiectasis. These include cystic fibrosis, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, and immunoglobulin A (IgA) and IgG deficiency.

Table 89-1 Surgical Spectrum of Bacterial Infections of the Lung and Bronchial Compressive Disease | |

|---|---|

|

Table 89-2 Etiology of Bronchiectasis | |

|---|---|

|

The distribution and frequency of bronchiectasis is given in Tables 89-4 and 89-5. The distribution to some extent is characteristic of the etiology. For example, in patients with Kartagener’s syndrome, hypogammaglobulinemia, and cystic fibrosis, the areas of involvement are generally diffuse and bilateral and involve multiple cystic segments of both upper and lower lobes. Tuberculosis is either unilateral or bilateral and generally involves the upper lobes or superior segment of the lower lobes. Middle lobe syndrome is caused by the involvement of lymph nodes and the middle lobe bronchus from a granulomatous process.

Table 89-3 Classification of Bronchiectasis | |

|---|---|

|

Table 89-4 Anatomic Distribution of Bronchiectasis in Order of Frequency | |

|---|---|

|

Clinical Diagnosis

Clinical bronchiectasis is characterized by repeated episodes of respiratory tract infection. The key symptom is cough, with mucopurulent and tenacious secretions lasting months to years. This may be accompanied by intermittent hemoptysis, dyspnea, wheezing, and pleurisy. It is most frequently characterized by clinically repeated episodes.

Methods of Diagnosis

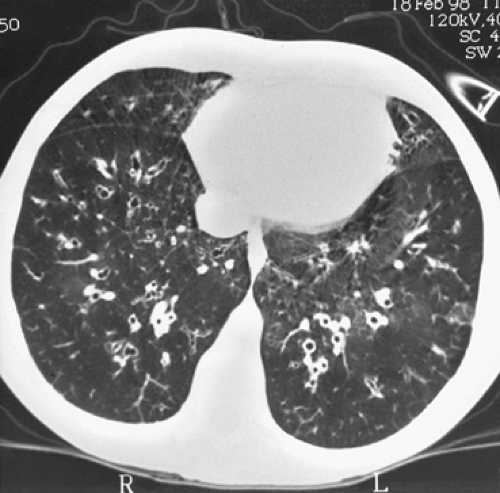

After a thorough history and physical examination, the most frequently used techniques in the diagnosis of bronchiectasis are imaging modalities, fiberoptic bronchoscopy, and bronchograms. Before the advent of computed tomography (CT), a bronchogram was the standard procedure for diagnosis (Fig. 89-1). A high-resolution CT scan has replaced this procedure in the diagnosis of bronchiectasis. The detailed images demonstrate bronchial dilatation, peribronchial inflammation, and parenchymal disease. According to Barker,5 the diagnosis can be made with a 2% false-negative and a 1% false-positive rate. Figure 89-2 shows a typical high-resolution CT scan for lower lobe bronchiectasis.

Treatment of Bronchiectasis

An outline for the medical and surgical management of bronchiectasis is given in Table 89-6. The goals of medical management include prevention and control, appropriate antibiotic therapy, and postural drainage.

Surgical management of bronchiectasis has strict limitations and guidelines. It is based on three premises: (a) the disease is segmental and unilateral, (b) complete resection of all disease is possible, and (c) complete resection of all disease prevents recurrence.

Table 89-5 Frequency of Distribution of Bronchiectasis: Area of Involvement | |

|---|---|

|

This does not apply to those patients with immunologic or genetic abnormalities. Specific surgical indications are listed in Table 89-6. The immediate goal of surgical resection is the removal of most, preferably all, involved segments or lobes and preservation of nonsuppurative areas. The results of surgical resection for bronchiectasis are given in Table 89-7. Hodder and associates18 reported that the mortality rates vary from 0% to 8.3%.

Table 89-6 Treatment of Bronchiectasis | |

|---|---|

|

Lung transplantation may be performed for patients with suppurative lung disease. Barker5 noted that of 3,160 lung transplants reported by the St. Louis Lung Transplant Registry in 1994, a total of 466 patients underwent transplantation for cystic fibrosis and 82 for bronchiectasis. The actuarial survival rate for patients with cystic fibrosis is 72% at 1 year and 57% at 3 years.

Lung Abscess

Lung abscess has been recognized since the time of Hippocrates; Wiedemann and Rice43 quote Hippocrates:

As time goes by, the fever becomes more severe, coughing begins, and the patient cannot lie any more on the healthy side but only on the diseased side. The feet and eyes swell. When the 15th day after the rupture has occurred, prepare a warm bath, sit him upon a stool, shake him by the shoulders and listen to where the noise is heard. At that place, make an incision then it produces death more rarely.

Before the antibiotic era, it was realized that unless drainage was achieved, death was inevitable. With the development of antibiotics, treatment improved and mortality decreased. With the development of increasing numbers of immunosuppressed individuals and the increased incidence of nosocomial pneumonia, lung abscess continues to be a problem for practicing thoracic surgeons.

Geppert16 defines a lung abscess as a subacute pulmonary infection in which the chest radiograph shows a cavity within the pulmonary parenchyma. It is a localized collection of pus contained within the cavity formed by the disintegration of the surrounding tissues. An abscess is defined as acute when the duration of symptoms is <6 weeks. In general, the abscess is

solitary, but it may occasionally be multiple, particularly in the immunocompromised individual.

solitary, but it may occasionally be multiple, particularly in the immunocompromised individual.

Table 89-7 Results of Surgical Resection for Bronchiectasis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 89-8 Classification of Lung Abscess | |

|---|---|

|

A classification of lung abscess is given in Table 89-8. Contributing factors to the development of a lung abscess are listed in Table 89-9. Anaerobic infections remain the most frequent etiologic agents. Periodontal disease and aspiration are the two most frequent causes. Fewer than 20% of patients with an anaerobic lung abscess do not have a history of one or the other of these aforementioned causes.

The typical patient has a history of an antecedent event or of pulmonary infection or pneumonia. Patients have an intermittent febrile course with weight loss, night sweats, and cough. Later in the course, the production of purulent sputum becomes common. The patient may have foul breath and often appears quite ill.

The most frequent microorganisms associated with lung abscess are listed in Table 89-10. The microorganism is most likely related to the etiologic cause. The most frequent anaerobic cause is Bacteroides and the most frequent aerobic causes are Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Diagnostic techniques include a complete history and physical examination with emphasis on a predisposing event such as dental work or possible aspiration. The symptoms of fever and purulent foul-smelling sputum are highly suggestive. Analysis of the sputum is necessary in the attempt to identify the causative microorganism.

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy is indicated for two reasons. It helps in the bacteriologic assessment with the use of a sterile brush and in obtaining bacterial washings for bacterial analysis. It is also important to rule out an endobronchial tumor or obstruction and to determine whether the abscess is draining internally.

Table 89-9 Contributing Factors to Lung Abscess | |

|---|---|

|

Table 89-10 Bacteriology of Lung Abscess | |

|---|---|

|

Radiographic imaging is generally required to determine the presence of a lung abscess with certainty. Posteroanterior and lateral chest radiography and CT scanning of the chest are the most frequently used modalities (Figs. 89-3 and 89-4). The most frequent sites of involvement are the superior segments of the right and left lower lobes and the lateral part of the posterior segment of the right upper lobe (the axillary subsegment) (Fig. 89-5). Ninety-five percent of all lung abscesses occur in these locations.

The differential diagnosis of cavitary lung lesions revolves around four entities: (a) cavitating carcinoma, generally squamous cell; (b) tuberculous or other fungal diseases; (c) pyogenic lung abscess; and (d) empyema with bronchopleural fistula. The patient’s history is important in separating the differential diagnosis. Hood19 suggested that the absence of fever, lack of purulent sputum, and a normal white blood cell count should raise strong suspicion of an underlying neoplasm.

Once the diagnosis is established, appropriate therapy must be instituted. Principles of therapy are given in Table 89-11. The etiologic organisms must be identified as quickly as possible through the techniques previously discussed. Appropriate antibiotics should be instituted based on drug sensitivity. If an aerobic microorganism is suspected, the patient is generally started on clindamycin and gentamicin while awaiting sensitivity study results. Antibiotics are continued for a prolonged period, generally 6 to 8 weeks.

Adequate drainage must be achieved by chest physiotherapy, fiberoptic bronchoscopy, or percutaneous catheter drainage. Only when the abscess does not drain internally into the tracheobronchial tree is external drainage indicated. Wiedemann and Rice43 reported that 80% to 90% of aerobic lung abscesses respond to medical therapy.

When the abscess does not drain internally and the patient experiences a septic course, external drainage can be achieved by closed-tube thoracostomy, CT-directed catheter drainage, or pneumonostomy (Fig. 89-6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree