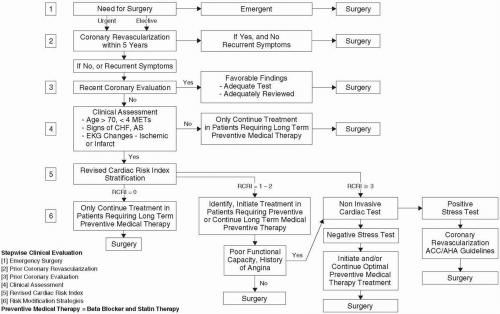

Practice Guidelines (11), and empiric risk indices (13,14), such as the Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) (14).

Is noncardiac surgery urgently required?

Has the patient undergone recent coronary revascularization?

Has the patient been evaluated for CAD in the past 2 years?

Is patient at risk for adverse cardiac events?

What is the risk of cardiac complication in relation to severity of the surgical procedure?

What is the RCRI?

Is a noninvasive cardiac test necessary?

Is there a benefit for perioperative coronary revascularization?

What additional preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative risk modification besides coronary revascularization should be initiated?

What long-term risk-stratification and management strategies should be implemented?

to stratify the patient further by using RCRI, and if indicated, to postpone surgery until the cardiac problem is adequately worked up and optimally treated, if necessary (Fig. 38.1). Patients with moderate or excellent functional capacity and one or more intermediate predictors of clinical risk can normally undergo low- and intermediate-risk surgery (Table 38.2) with low perioperative cardiac risk. Conversely, patients with poor functional capacity or a combination of high-risk surgery, moderate functional capacity, and intermediate clinical predictors of cardiac risk (especially two or more) should be evaluated by further RCRI stratification. In general, patients with minor or no clinical predictors of risk and with moderate or excellent functional capacity [greater than four to six metabolic

equivalents (METs)] can safely undergo most types of noncardiac surgery with low risk of cardiac complications (11,16,17).

TABLE 38.1. Clinical predictors of increased perioperative cardiovascular risk (myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, death) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 38.2. Surgery-specific cardiac risk (combined risk of cardiac death and nonfatal myocardial infarction) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 38.3. Functional-capacity assessment from clinical history | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

capacity in properly risk-stratifying patients before noncardiac surgery (11,13,27,28).

TABLE 38.4. Revised cardiac risk index clinical markers | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

tolerance suggests that they are intermediate to high risk regardless of planned major noncardiac surgery (11). Based on the RCRI score, evidence-based medical therapy is appropriate to reduce perioperative cardiovascular risk in selected intermediate (RCRI score 1 to 2) to high-risk (RCRI score 3 or more) patients (14). A stepwise approach is illustrated in Fig. 38.1. Patients with an RCRI score of 3 or more should be considered for either preoperative noninvasive cardiac testing or initiation of perioperative medical therapy if either limited or no ischemia occurs during stress testing or if risks of coronary revascularization are thought to exceed any potential benefit. An RCRI score greater than 3 in patients with severe myocardial ischemia suggestive of left main or three-vessel disease should lead to consideration of coronary revascularization before noncardiac surgery for appropriate patients.

risk when positive. The presence of thallium redistribution, especially in increasing numbers of myocardial segments, identifies patients at high risk of perioperative cardiac complications (38,42), whereas the presence of fixed defects identifies patients at intermediate risk, particularly for late cardiac events (41).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree