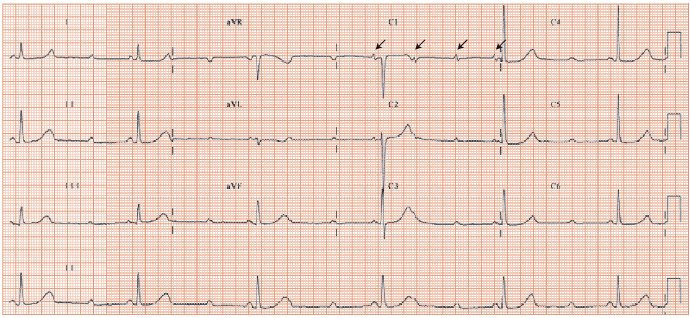

Fig. 32.2 Heart block in aortic stenosis (AS). Elderly female, breathless, severe AS. Three P waves for every QRS complex – two are easily seen, the third is at the end of the T wave, disguised in most leads, but well seen in lead V1. Each QRS has a preceding P wave with the same PR interval, i.e. the diagnosis is Mobitz type 2 heart block or ‘3 to 1 heart block’. QRS complex normal aside from borderline voltage criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) – S V2 + R V5 = 42 mm (normal ≤ 35 mm). Cardiac ultrasound showed severe AS, moderate LVH.

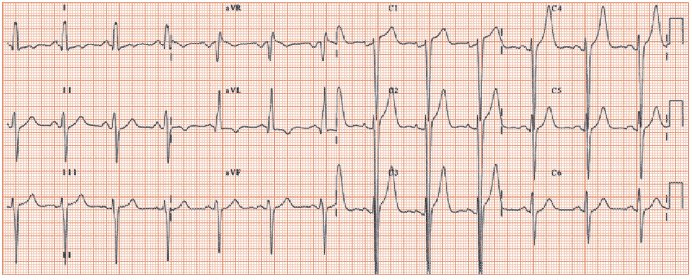

Fig. 32.3 Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, resting left ventricular outflow tract gradient 80 mmHg. Sinus rhythm, left atrial enlargement (prominent late negative deflection in lead V1), normal PR interval, left axis deviation (lead II and II negative, lead I positive; QRS axis –46°). QRS duration increased (123 ms), best shown in lead aVL. Gross left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) (aVL = 15 mV, normal ≤ 11 mV; and S V2 (55 mm!) + R V5 = (6 mV) = 61 mV (normal ≤ 40 mV). Inverted T wave in lead aVL (‘strain’ pattern). Poor anterior R wave progression, partly due to left axis deviation. The LVH is extreme; this ECG could also be from a patient with aortic stenosis, or severe hypertension.

Aortic stenosis

Common and serious, aortic stenosis (AS) relates to:

- Rheumatic heart disease (very rare in developed countries), usually in young adults.

- Bicuspid aortic valve (1–2% of the population); the valve works well for years, then degenerates in middle age.

- Calcific degeneration in a previously normal valve, the commonest cause, relates to the same factors underlying coronary artery disease (age, cholesterol, vascular inflammation), very common in the elderly (≥ 65 years).

Prognosis and ECG findings

Aortic stenosis progresses slowly, with the peak pressure drop over the valve increasing by 4–6 mmHg/year. A gradient of ≥ 50 mmHg (valve area ≤ 1 cm2) is required for symptoms (effort-dependent breathlessness, angina and syncope). Sudden cardiac death is very rare (1–2%) in asymptomatic severe AS, but common once symptoms develop. The prognosis in the absence of surgery with symptoms is poor; if angina is the presenting symptom (the case in 35%), half die by 5 years; if syncope (15%), half die by 3 years; and if dyspnoea (50%), half die within 2 years. Hence, once symptoms occur, surgery should be undertaken without delay. The ECG does not aid the timing of surgery as this is based on symptoms, possibly aided by the exercise stress test in highly selected asymptomatic patients.

The slow increase in the aortic valve narrowing allows increasingly substantial left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) to develop. So, the ECG correlates of valvar AS are of increasingly obvious ECG LVH (Fig. 32.1). When symptoms occur, most (≥ 80%) patients have ECG LVH; many also show ‘repolarization changes’; a few show only repolarization changes (usually the obese or elderly). A very few (especially the elderly) with symptomatic AS do not show ECG LVH and the ECG may be normal. This illustrates a general principle; stimuli to ECG changes are more likely to result in classic changes in the young than in the elderly. Calcific AS is associated with high-grade heart block (second/third degree) as the calcium burrows from the valve into the interventricular septum to disrupt the conducting tissue (Fig. 32.2), when it may lead to syncope. Asymptomatic complex ventricular ectopy is common.

Valvar AS needs to be differentiated from other causes of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction:

- Supra-valvar obstruction, exceptionally rare, presents in infancy.

- Infra-valvar obstruction:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree