Antireflux Surgery

John G. Hunter

Jeffrey S. Fronza

INTRODUCTION

Peptic esophageal injury was first described in the late 19th century, but became more frequently recognized with the advent of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. The association of peptic esophageal injury and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was demonstrated in the 1930s. It was not until the association of hiatal hernia and GERD was recognized in the 1950s, however, that antireflux surgery emerged. The 360 degree fundoplication to treat GERD was reported in 1955 by Rudolf Nissen, a Swiss surgeon. Nissen’s fundoplication created a long, super competent lower esophageal sphincter (LES), which in turn frequently led to postoperative bloating, dysphagia, inability to belch, and flatulence. In the 1980s, Donahue and DeMeester perfected the short, floppy Nissen fundoplication by dividing the short gastric and retrogastric attachments, shortening the wrap to 1 to 2 cm, and performing the wrap around a large Maloney dilator. By better allowing gas to vent from the stomach, this modification avoided most of the unwanted side effects while still controlling pathologic reflux.

In 1992, the New England Journal of Medicine published a seminal study from the Veterans Administration that showed open Nissen fundoplication to be superior to continuous medical therapy in patients with complicated GERD. That same year, the field of antireflux surgery was revolutionized when Bernard Dallemagne of Belgium and Alfred Cuschieri of Scotland performed the first laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication (LNF). Between 1990 and 1997, the annual rate of LNF more than doubled. Rates have decreased since that time for a variety of reasons, including improper technique and an unacceptable rate of recurrent GERD mainly due to inexperience on the part of the surgeon. In spite of this, LNF remains the gold-standard treatment of GERD with multiple studies demonstrating control of reflux at 10 years in 90% of patients. Continued successful surgical correction of GERD requires both adherence to proper surgical technique and appropriate patient selection.

INDICATIONS

INDICATIONSGERD is the most common disease of the alimentary tract requiring medical or surgical treatment. It affects 7% of adults in the United States on a daily basis and >30% on a regular basis. In addition, 5% to 15% of these individuals experience serious complications of GERD such as esophageal stricture or Barrett’s esophagus. Typical symptoms of GERD include heartburn, regurgitation, and dysphagia. Atypical symptoms include cough, hoarseness, wheezing, and chest pain. Nonoperative treatment of GERD involves lifestyle modifications such as weight loss, avoidance of food intake for several hours prior to retiring to bed, elimination of food and medications that promote LES dysfunction, cessation of smoking, and elevation of the head of the bed. Many patients require pharmacologic treatment such as daily use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs). Quality-of-life assessments performed on patients with severe GERD reveal scores similar to patients with chronic congestive heart failure, emphasizing the debilitating effect of this disease.

Patients whose symptoms are refractory to PPIs are candidates for LNF, as are those whose symptoms are controlled on PPIs, but who prefer to avoid life-long need for medication. Studies have demonstrated LNF to be cost-effective in young patients with severe GERD. Those with predominant respiratory symptoms are another group best served with LNF as only 50% have symptom control with medication. That being said, those patients responsive to PPIs and with typical symptoms of GERD have the best outcomes from operation. The current recommendation is to consider operation for heartburn patients responsive to medication, but with frequent troublesome symptoms poorly treated by PPIs, such as regurgitation and respiratory symptoms. Patients with large hiatal hernias are unlikely to have their symptoms of postprandial chest pain and regurgitation adequately treated with PPIs.

A relative contraindication to LNF is morbid obesity (BMI >40), as these patients have an increased risk of recurrent GERD and are better served with a roux-en-Y gastric bypass to not only control their GERD but also for optimal weight loss.

PRINCIPLES OF ANTIREFLUX SURGERY

Prior to offering an antireflux operation, a thorough preoperative evaluation must be completed. In a patient with typical or atypical symptoms of GERD, the diagnosis is confirmed by endoscopic evidence of erosive esophagitis, peptic stricture, or Barrett’s esophagus or by a 24-hour ambulatory esophageal pH study revealing a pH of <4 for >4.2% of the study period. Even with an abnormal pH study, an upper endoscopy is essential to document sequelae of GERD and to rule out other pathology masquerading as GERD. Finally, esophageal manometry assesses esophageal motility. Previously, it was thought that ineffective esophageal motility (>60% ineffective swallows or <40 mmHg mean distal esophageal contraction pressure) was an indication for partial fundoplication, but it is clear now that impaired esophageal bolus clearance after Nissen fundoplication is only a risk in the presence of aperistalsis. Video barium swallow is indicated to evaluate an associated hiatal hernia and/or a shortened esophagus. A nuclear medicine gastric emptying study is recommended in patients with diabetes or symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and early satiety as those found to have delayed emptying will benefit from pyloroplasty at the time of LNF.

The objective of any antireflux operation is to reconstruct a LES that has been rendered mechanically defective due to hypotension, inappropriate relaxation, and/or intrathoracic displacement. Guiding surgical principles include the establishment of an adequate intra-abdominal length of esophagus (>3 cm), reduction and repair of an associated hiatal

hernia, and tension-free construction of an appropriate fundoplication. All fundoplications should restore the acuteness of the angle of His and calibrate the fundoplication diameter to be loose around an 18 to 20 mm esophageal dilator. There is consensus within the surgical community that a laparoscopic approach is preferred in the vast majority of patients undergoing fundoplication. Thoracotomy is indicated only in specific reoperative settings, where a hostile upper abdomen makes a transthoracic approach appealing.

hernia, and tension-free construction of an appropriate fundoplication. All fundoplications should restore the acuteness of the angle of His and calibrate the fundoplication diameter to be loose around an 18 to 20 mm esophageal dilator. There is consensus within the surgical community that a laparoscopic approach is preferred in the vast majority of patients undergoing fundoplication. Thoracotomy is indicated only in specific reoperative settings, where a hostile upper abdomen makes a transthoracic approach appealing.

PATIENT PREPARATION

Patients should be maintained on PPIs preoperatively to minimize esophagitis. Peptic strictures should be dilated preoperatively. Anticoagulants and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents are discontinued. Glucose control should be optimized, and cardiopulmonary disease should be thoroughly evaluated with appropriate consultation and testing preoperatively. The patient should be nil per os the night prior to surgery. Perioperative antibiotics are unnecessary as antireflux surgery is a clean operation.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

SURGICAL TECHNIQUESLaparoscopic Nissen Fundoplication

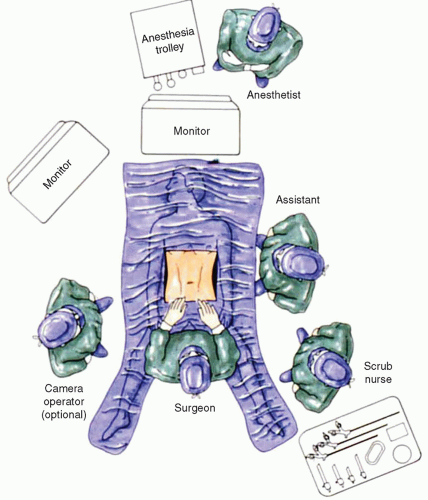

LNF is generally performed in the supine position with the legs extended and abducted 30 to 60 degrees so that the surgeon may operate between the legs. Low lithotomy is a less desirable position as peroneal nerve injury, deep venous thrombosis, and patient movement while in reverse Trendelenburg position is more frequent. Some surgeons prefer the patient in the supine position, operating from either the left or the right side. This setup, however, results in poor ergonomics with resultant chronic shoulder injuries in the surgeon and the need to address the hiatus obliquely. Clearly, optimal positioning favors a split-leg position. The assistant standing to the left of the patient holds the camera with the left hand and assists with the right hand. The monitor is placed over the patients head ideally fixed on a ceiling-mounted boom (Fig. 16.1).

LNF is performed with a five-port technique. The operation begins by insufflating the abdomen with a Veress needle placed above the umbilicus. After obtaining pneumoperitoneum, an 11-mm trocar is placed 15 cm below the costosternal junction slightly to the left of the midline. By placing the port to the left of midline, and obliquely entering the abdomen—aiming toward the esophageal hiatus—the surgeon minimizes the risk of port-site hernia, stays out of the fatty ligamentum teres, stays further away from the left lobe of the liver, and more accurately aligns the laparoscope with the trajectory of the esophagus (right to left) as it traverses the diaphragm. A 45-degree laparoscope is introduced and a brief abdominal survey is performed. All other trocars are placed under direct vision and all sites are infiltrated with local anesthesia before an incision is made. The second 11 mm trocar is introduced along the left costal margin 12 cm from the base of the sternum. The 11 mm trocar facilitates the passage of suture and is useful for the placement of endoscopic clips when necessary. The third trocar placed is 5 mm, generally located 8 cm farther down the left costal margin than the second trocar but not further lateral than the anterior axillary line. A Nathanson liver retractor is introduced through the track of a cutting 5 mm port that has been placed and removed just inferior and left of xiphoid. The liver retractor is connected to a mechanical arm fixed to the right side of the operating table. The optimal position of the liver retractor allows access to the anterior arch of the hiatus as well as thoroughly defining the right crus of the diaphragm. The patient is then placed in steep reverse Trendelenburg position. The fifth trocar is used for the surgeon’s left hand and is placed along the right costal margin just inferior to the edge of the retracted left lobe of the liver. The point at which this trocar is placed is determined by internal, not external, anatomy, and therefore is variable in its

superficial projection. It is generally desirable to have this trocar as high and as wide as possible without going into the left lobe of the liver or achieving placement to the right side of the falciform ligament.

superficial projection. It is generally desirable to have this trocar as high and as wide as possible without going into the left lobe of the liver or achieving placement to the right side of the falciform ligament.

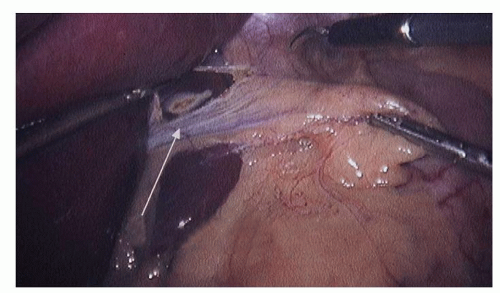

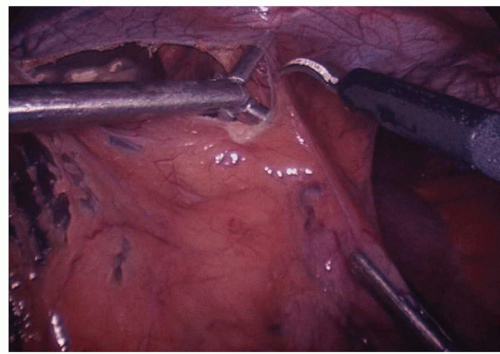

Dissection commences by the assistant grasping the epiphrenic fat pad and retracting inferiorly and slightly toward the patient’s left. This reduces any hiatal hernia and places the phreno esophageal membrane on tension. Next, the surgeon exposes the right crus of the diaphragm by opening the gastro hepatic ligament above and below the hepatic branch of the vagus (Fig. 16.2). While it is desirable to preserve the hepatic branch of the vagus, many surgeons routinely divide it to obtain better access to the right crus. A blunt atraumatic grasper is placed beneath the phrenoesophageal ligament to establish the plane between the esophagus and the diaphragm. This layer is divided with ultrasonic energy (Fig. 16.3). The dissection proceeds around the arch of the hiatus and down the left pillar of the diaphragm as low as is easily visualized. Access to the mediastinum is obtained by placing two blunt graspers (closed) between the esophagus and the right crus of the diaphragm, and then spreading horizontally. This is repeated on the left side of the esophagus. The anterior vagus nerve is generally affixed to the esophagus, and the posterior vagus nerve is not visible at this time. Dissection down the right crus of the diaphragm continues until the surgeon reaches its base where the left crus is visualized emerging from posterior to the esophagus. This completes the preliminary phase of the crural dissection.

The next phase of dissection includes the division of the short gastric arteries, and posterior mobilization of the stomach. The light cord of the laparoscope is rotated 30 degrees counterclockwise (11 o’clock position), and the surgeon grasps the greater curvature of the stomach at the level of the inferior pole of the spleen. The assistant grabs the greater omentum adjacent to the greater curvature of the stomach. The surgeon retracts the stomach to the patient’s right and posteriorly while the assistant elevates the omentum anteriorly and to the patients left. The ultrasonic shears are introduced and entry to the lesser sac is gained by incising the greater omentum adjacent to the greater curvature of the stomach (Fig. 16.4). Several applications of the harmonic scalpel may be necessary to gain access to the lesser sac in heavier patients. It is important that the short gastric vessels are visualized and completely occluded with the ultrasonic shears before the application of energy. Incomplete division of short gastric vessels results in troublesome bleeding. As the dissection moves cephalad, the surgeon keeps moving the retraction point higher along the greater curvature, generally placing one jaw of the atraumatic grasper on the anterior wall of the stomach and one jaw on the posterior aspect of the stomach. The assistant places one jaw of their grasper in the lesser sac, and one jaw in the greater sac to optimally retract the greater omentum.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree