Anterior Transthoracic Approaches to the Spine

Kamal Mansour

In the last half of the twentieth century, the anterior transthoracic approaches to the spinal column became the preferred techniques to manage most problems involving the lower cervical, thoracic, and upper lumbar portions of the spine in children and adults. Hodgson and Stock12 in Hong Kong were the first to use anterior spinal fusion in the radical treatment of Pott’s disease and Pott’s paraplegia tuberculosis of the spine. The reports of Cauchoix and Binet5 suggested the use of median sternotomy to expose the vertebral bodies from C7 to T4. Perot and Munro25 described the transthoracic removal of midline thoracic disc protrusions causing spinal cord compression. Harrington11 described the use of methylmethacrylate for vertebral body replacement and anterior stabilization of pathologic fracture-dislocations of the spine due to metastatic disease. Cook6 was also among the initial surgeons to bring to the attention of American surgeons the anterior thoracic approach to the spine. In addition to these early reports, a large volume of publications on this subject has been recorded in orthopedic and neurosurgical, as well as general thoracic literature over the past 30 years. Mack and associates16 were the first to report the application and techniques of video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) for the spine. The improvement of VATS has increased the application of minimally invasive techniques to anterior transthoracic approaches to the spine.

Indications

The indications for the use of a transthoracic approach for exposure of the spine are the presence of a destructive process of one or more vertebral bodies or intervertebral disks, fractures of the thoracic or lumbar spine, and major spinal deformities (Table 48-1). The incidence of the various lesions managed by these anterior approaches varies in children and adults. Spinal deformities are much more common in children and adolescents, whereas degenerative disorders, both infectious and malignant, are more common in adults. Spinal deformities are the result of idiopathic disease, neuromuscular disorders, hemivertebra fracture, pseudoarthrosis, Scheuermann’s disease, and tumors, primarily neurofibromatosis, as well as some other uncommon causes. In contrast, in adults, Anderson and associates2 found the indications for these approaches to be (a) the presence of a herniated nucleus pulposus (30%), (b) metastatic disease to the spine (27%), (c) infection (22%), (d) spinal deformities (12%), (e) fracture (6%), and (f) primary tumors involving the spine (3%). In regard to metastatic tumors and primary tumors of the spine or an adjacent structure such as the lung and mesenchymal or neurogenic tumor, McAfee and Zdeblick19 and Walsh and coworkers27 have noted that metastatic disease was by far the most common cause of destruction of a vertebral body. The common primary tumors are of the lung, kidney, breast, melanoma, multiple myeloma, pancreas, and thyroid. The indications for operation in these patients are severe pain or impending paraplegia. Among the tumors that may secondarily involve a vertebral body are lesions from the lung (primarily superior sulcus tumors), neurogenic tumors such as neuroblastoma, or ganglioneuroblastomas as well as the benign neurofibromas, Wilms’ tumor, and mesenchymal tumors such as liposarcomas, chondrosarcomas, and chordomas. Primary tumors of the vertebral body are uncommon and include osteosarcoma, plasmacytoma, and chondrosarcoma. Operation may be for cure or at times only for palliation. Rarely, an astrocytoma may require a spinal decompression, as noted by Naunheim and associates.23 A destructive aneurysmal bone cyst, as recorded by Janik and colleagues,15 may require vertebrectomy and spinal stabilization. Last, traumatic injury with fracture and impending or present neurologic complications has been a major indication for transthoracic exposure of the lower cervical, thoracic, or thoracolumbar spine, as recorded in the series of McElvein20 and of Naunheim23 and their associates.

The major indications for spinal operations are the relief of pain, stabilization of deformities, cosmesis, drainage of areas of spinal infection, and progression of neurologic changes indicative of cord compression that may result in paresis or paralysis.

Using a multidisciplinary approach with thoracic, orthopedic, or neurologic surgeons for the patient with a spinal disorder results in improved quality of care. The advantages of the thoracic surgeon being involved are improved preoperative physiologic assessment, expedient surgical exposure, and expertise in postoperative care. The major advantages of the anterior thoracic approach to the thoracic and lumbar spine are improved visualization and increased ease of access to the area of involvement with the exposure provided.

Table 48-1 Etiologies of Spinal Disorders That Indicate Anterior Thoracic Approaches | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Special Preoperative Considerations

Cardiopulmonary Evaluation

Certain principles will help the general thoracic surgeon to improve the quality of care to the patient. Since the most prevalent complications after this approach are pulmonary, an adequate assessment of the physiologic status of the respiratory system as determined by pulmonary function studies and arterial blood gases help in planning preoperative and postoperative care.5 An assessment of the cardiovascular system when indicated should decrease unsuspected postoperative complications. When major chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is present, the operation may be canceled or the patient may be given preoperative pulmonary preparation.

Preoperative Embolization

Preoperative embolization may become necessary in some patients with metastatic disease involving a vertebra (e.g., renal cell carcinoma and thyroid carcinoma) because such entities may involve excessive vascularity of the metastatic lesion. Walsh and associates27 suggested preoperative embolization to reduce excessive blood loss. This procedure was performed in eight of their patients, but in three of these a major complication occurred: an asymptomatic aortic dissection, transient Brown-Séquard syndrome that improved significantly, and a spinal artery syndrome that resulted in paraplegia that did not improve with time. It would appear that embolization should be resorted to only if absolutely necessary.

Anesthesia

General endotracheal anesthesia with a single-lumen tube is sufficient for patients undergoing cervical approaches (C7–T2). A double-lumen tube is the preferred method in thoracic and lumbar approaches (T2–L2) and all VATS approaches. A single-lumen tube with a bronchial blocker can be used, but this technique is very anesthesiologist-dependent and can prolong operative time if occlusion is lost. In performing an anterior approach followed immediately by a posterior approach, care must be taken to change the double-lumen endotracheal tube to a single-lumen tube before turning the patient to the prone position. Delaying the change of the endotracheal tube until after the change to the prone position places the patient at increased risk secondary to swelling of the trachea and facial edema. Occasionally the airway may be difficult to intubate initially and a tube exchanger may have to be used to switch to a double-lumen from a single-lumen tube.

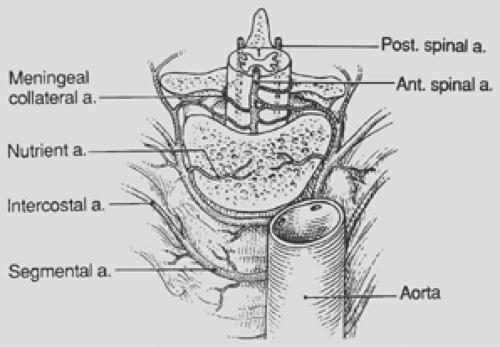

Spinal Blood Supply

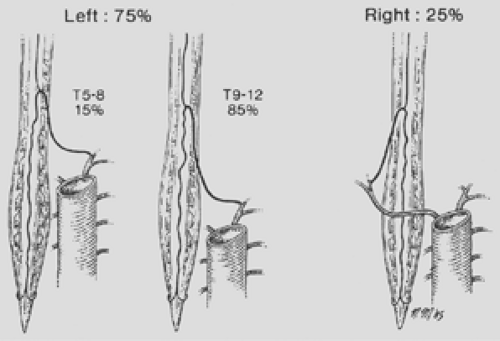

The thoracic surgeon must have specific knowledge of the segmental arteries. Paired segmental arteries at every vertebral level supply intraspinal and extraspinal structures. The anatomy of the segmentals and their relationship to intercostal and anterior spinal arteries is shown in Figure 48-1. The lower cervical region is supplied by radicular branches of the vertebral, thyrocervical, and costocervical arteries. The thoracic and lumbar arteries arise from the aorta. The segmental arteries should be ligated unilaterally and close to the aorta so that the collateral supply from the intercostal arteries to the spinal cord remains intact, thus preventing ischemia. The collateral supply to the spinal cord is redundant in the cervical and lumbar regions compared with level of the T4 to T9, which has poor collateral supply and represents the narrowest area of the spinal cord. This latter area is called the “critical vascular zone of the spinal cord,” and interference with its vascular supply is likely to result in paraplegia. The artery of Adamkiewicz is the largest feeder to the anterior and posterior spinal artery in the lumbar area. It arises on the left side in 75% to 80% of patients between the bed of T7 and L4, most often at the level of T8 to T10 (Fig. 48-2). Selective angiography of this vessel with avoidance of the artery may be helpful in deciding on the surgical approach and preventing paraplegia. There is controversy as to whether this vessel must be visualized by preoperative angiography before operation on the lower thoracic spine, but many, including McElvein,20 believe

it is unnecessary. It is our practice, however, to perform spinal angiography in patients who require bilateral ligation of the segmental vessels and in those with congenital kyphosis, where arteriovenous malformations are common. Evoked potentials are obtained to ensure that injury to the spinal cord does not occur.

it is unnecessary. It is our practice, however, to perform spinal angiography in patients who require bilateral ligation of the segmental vessels and in those with congenital kyphosis, where arteriovenous malformations are common. Evoked potentials are obtained to ensure that injury to the spinal cord does not occur.

Figure 48-1. Anatomy of segmental arteries in relation to aorta and intercostal arteries. a., artery; Ant., anterior; Post., posterior. |

Patient Positioning

Proper patient positioning is the most commonly overlooked step in thoracic surgery. It is extremely important to position the patient appropriately to simplify the operation but also to protect the patient from significant morbidity involved with lengthy operations. In a cervical thoracic approach (C7–T2) the patient is in a supine position with arms tucked and padded by the side. The head is slightly turned to either the right or left to expose the anterior neck area. In an upper thoracic (T2–T6) and thoracic (T6–T12) and VATS approach, the patient is placed in either a left lateral decubitus position or a right lateral decubitus position. Care is taken in turning the patient that all lines and indwelling catheters are moved with the patient. A standard beanbag can be used to hold the patient in place, but other techniques such as sticky rolls have also been used satisfactorily. An axillary roll should be placed to prevent brachial plexus injury. Care is taken to pad all areas of the patient with direct contact to a hard surface. In lower thoracic and upper lumbar (T12–L3) approaches, the patient is placed supine with the thorax in a slight right lateral decubitus position with the hips lying parallel to the operating room table. With this positioning, the retroperitoneal abdomen can be approached if necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree