Anterior Approach to Superior Sulcus Lesions

Phillippe G. Dartevelle

Sacha Mussot

Chuong D. Hoang

Henry K. Pancoast,21 a radiologist at the University of Pennsylvania, described a patient afflicted with a carcinoma of uncertain histologic origin occupying the extreme apex of the chest; it was associated with shoulder and arm pain, atrophy of the hand muscles, and Horner’s syndrome. This clinical entity has become known as Pancoast’s syndrome. Unknown to Pancoast, Tobias had already characterized the anatomic and clinical aspects of this lesion, correctly recognizing that the tumor was a peripheral lung cancer. Anatomically, the pulmonary sulcus comprises the costovertebral gutter extending from the first rib to the diaphragm. The superior pulmonary sulcus lies at the uppermost extent of this recess, as reviewed by Teixeira.27 Generally, it is understood that non-small-cell lung carcinomas of this region are called Pancoast tumors, and we refer to them as such throughout. However, the term superior sulcus lesion encompasses other, more diverse etiologies, both benign and malignant. Furthermore, this definition has been expanded to include cases that do not include evidence of brachial plexus or stellate ganglion involvement. According to Detterbeck,8 chest wall involvement in this region might be restricted to the parietal pleura or might extend deeper to the upper ribs, vertebral bodies, or subclavian vessels. Invasion of the chest wall at or lower than the level of the second rib or of the visceral pleura only does not meet the criteria for a superior sulcus lesion. Additionally, Macchiarini and colleagues15 reported that a wide variety of superior sulcus lesions can result in Pancoast’s syndrome (Table 38-1); thus a histologic diagnosis is required when the syndrome is encountered.

Presentation

Superior sulcus lesions of non-small-cell histology account for less than 5% of all bronchial carcinomas, as reported by Ginsberg and associates.11 These tumors may arise from either upper lobe and tend to invade parietal pleura, endothoracic fascia, subclavian vessels, brachial plexus, vertebral bodies, or first rib. However, their clinical features are influenced by their location.

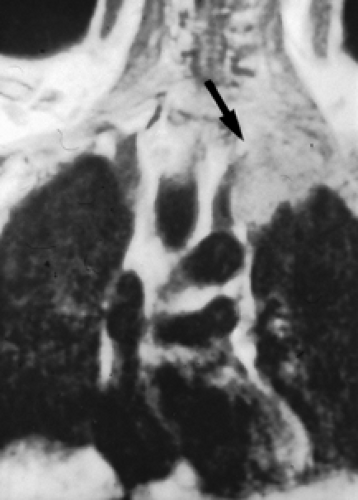

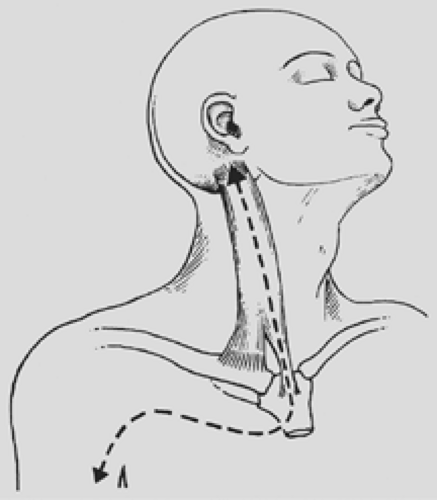

Tumors located anterior to the anterior scalene muscle may invade the platysma and sternocleidomastoid muscles, external and anterior jugular veins, inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle, subclavian and internal jugular veins including major branches, and the scalene fat pad (Fig. 38-1). They invade the first intercostal nerve and first rib more frequently than the phrenic nerve or superior vena cava. Patients usually complain of pain distributed to the upper anterior chest wall.

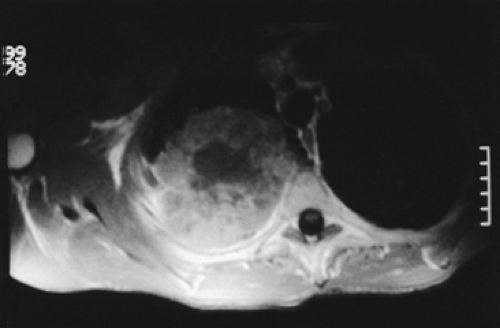

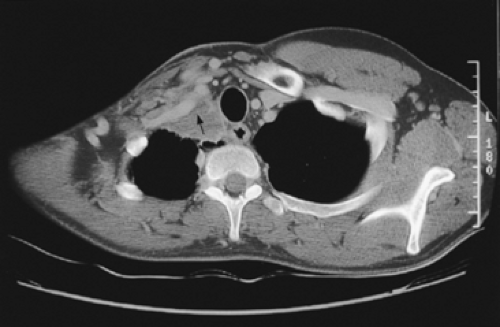

Tumors located between the anterior and middle scalene muscles may invade the anterior scalene muscle (phrenic nerve lying on its anterior aspect), the subclavian artery including primary branches except the posterior scapular artery, the trunks of the brachial plexus, and middle scalene muscle (Fig. 38-2). These tumors present with signs and symptoms related to the compression or infiltration of the middle and lower trunks of the brachial plexus (pain and paresthesia radiating to the shoulder and upper limb). Tumors lying posterior to the middle scalene muscles are usually located in the costovertebral groove and invade the nerve roots of T1, posterior aspect of the subclavian and vertebral arteries, paravertebral sympathetic chain, inferior cervical (stellate) ganglion, and prevertebral muscles. Some of these posterior tumors can invade transverse processes (Fig. 38-3) or extend to the vertebral bodies (only those abutting the costovertebral angle or extending into the intraspinal foramen without intraspinal extension may be resected).

Because of the peripheral location of these lesions, pulmonary symptoms—such as cough, hemoptysis, and dyspnea—are uncommon in the initial stages of the disease. Abnormal sensation and pain in the axilla and medial aspect of the upper arm in the distribution of the intercostobrachial (T2) nerve are more frequently observed in the early stage of the disease process. With further tumor growth, patients may present with overt Pancoast’s syndrome.

Preoperative Studies

Any patient presenting with signs and symptoms that suggest the involvement of the thoracic inlet should undergo a detailed preoperative evaluation to establish the diagnosis of bronchial carcinoma, assessing for operability. These patients usually present with small apical tumors that are hidden behind the clavicle and the first rib on routine chest radiographs. The diagnosis is established by history and physical examination, biochemical profile, chest radiographs, bronchoscopy with sputum cytology, fine-needle transthoracic or transcutaneous biopsy, and computed

tomography of the chest. A tissue diagnosis via video-assisted thoracoscopy may be indicated when other investigations are negative and to eliminate the possibility of pleural metastatic disease. If there is evidence of mediastinal adenopathy on computed tomographic scanning, mediastinoscopy is mandatory, since patients with clinical N2 disease are not candidates for surgery.

tomography of the chest. A tissue diagnosis via video-assisted thoracoscopy may be indicated when other investigations are negative and to eliminate the possibility of pleural metastatic disease. If there is evidence of mediastinal adenopathy on computed tomographic scanning, mediastinoscopy is mandatory, since patients with clinical N2 disease are not candidates for surgery.

Table 38-1 Causes of Pancoast’s Syndrome | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

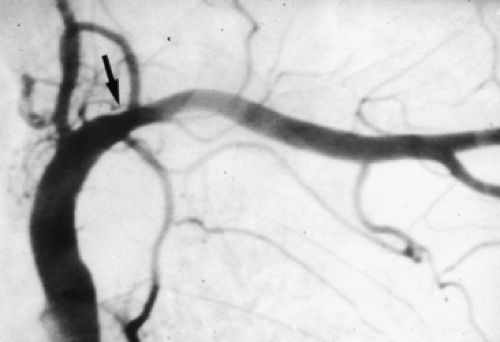

Neurologic examination, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or electromyography may delineate the tumor’s extension to the brachial plexus, phrenic nerve, or epidural space. Vascular invasion is evaluated by venous angiography, subclavian arteriography, Doppler ultrasonography (cerebrovascular disorders may contraindicate resection of the vertebral artery), or MRI (Fig. 38-4). Additional MRI is mandatory if the workup suggests tumor encroachment into the intervertebral foramina to rule out invasion of the extradural space (Fig. 38-5).

The initial evaluation also includes routine cardiopulmonary function tests and investigative procedures to identify the presence of any metastatic disease (e.g., positron emission tomography). Extrathoracic metastases are rare.

Figure 38-1. Computed tomography showing a bronchial carcinoma of the right superior sulcus invading the anterior thoracic inlet, including the subclavian vein (arrow). |

Treatment

Tumors of the superior sulcus are deemed universally and rapidly fatal lesions. It was believed that these tumors were not amenable to surgery until 1953, when Chardack and MacCallum4 successfully performed a lobectomy and chest wall excision followed by radiation therapy. Five years later, Shaw and colleagues26 approached superior sulcus tumors with preoperative radiation therapy (30–45 Gy in 4 weeks, including the primary tumor, mediastinum, and supraclavicular region), followed by surgical resection. This radiosurgical approach soon became the standard treatment, yielding better disease control and survival than other treatments. Ginsberg and colleagues11 provided evidence that en bloc resection of the tumor combined with external radiation (preoperative, postoperative, or both) must be considered the standard therapeutic approach for

superior sulcus tumors. The goal of resection is the complete removal of the upper lobe in continuity with the invaded ribs, transverse processes, subclavian vessels, T1 nerve root, upper dorsal sympathetic chain, and prevertebral muscles. More recently, preoperative concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy has been explored.3,13,14,23,29 The multimodality approach appears to lead to higher rates of completion resection, pathologic complete response, local control, and survival.

superior sulcus tumors. The goal of resection is the complete removal of the upper lobe in continuity with the invaded ribs, transverse processes, subclavian vessels, T1 nerve root, upper dorsal sympathetic chain, and prevertebral muscles. More recently, preoperative concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy has been explored.3,13,14,23,29 The multimodality approach appears to lead to higher rates of completion resection, pathologic complete response, local control, and survival.

Figure 38-4. Angiography illustrating a massive tumoral invasion of the intrascalenic left subclavian artery (arrow). |

In general, superior sulcus lesions not invading the thoracic inlet are completely resectable through the classic posterior approach of Shaw and colleagues.26 However, the posterior approach does not allow direct, safe visualization, manipulation, or complete oncologic clearance of all anatomic structures of the thoracic inlet. Superior sulcus lesions extending to the thoracic inlet should be resected by an anterior transcervical approach, according to our previous description.5

This operation has increasingly been accepted as a standard approach for all benign and malignant lesions of the thoracic inlet. Additionally, this approach facilitates exposure of the anterolateral aspects of the upper thoracic vertebrae. Contraindications to this approach include extrathoracic metastasis, invasion of the brachial plexus above the T1 nerve root, invasion of the vertebral canal or sheath of the medulla, massive invasion of the scalene muscles or extrathoracic muscles, mediastinal lymph node involvement, and advanced cardiopulmonary disease.

Anterior Transcervical Technique

One-lung anesthesia with measurements of urine output and body temperature is necessary. An arterial line opposite to the primary lesion and at least two venous lines for volume expansion should be used. The patient is supine with the neck hyperextended and the head turned away from the involved side. A bolster behind the shoulder elevates the operative field. The skin preparation extends from the mastoid downward to the xiphoid process and from the midaxillary line laterally to the contralateral midclavicular line medially.

An L-shaped cervicotomy incision is made, including a vertical presternocleidomastoid incision carried horizontally below the clavicle up to the deltopectoral groove (Fig. 38-6). To increase the exposure, the interception between the vertical and horizontal branches of the L-shaped incision is lowered to the level of the second or third intercostal space, depending on tumor extent. The incision is then deepened with cautery. The sternal attachment of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is divided. The cleidomastoid muscle, along with the upper digitations of the ipsilateral pectoralis major muscle, is scraped from the clavicle. A myocutaneous flap is then folded back, providing full exposure of the neck and cervicothoracic junction.

Once the inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle is divided, the scalene fat pad is dissected and sent for pathologic exam to exclude scalene lymph node metastasis. Inspection of the ipsilateral superior mediastinum after division of the sternothyroid and sternohyoid muscles is made by the operator’s finger along the tracheoesophageal groove. Tumor extension to the thoracic inlet is carefully assessed next. We recommend resection of the medial half of the clavicle only if the tumor is deemed resectable.

The jugular veins are dissected first, so that branches to the subclavian vein can eventually be divided. On the left side, li- gation of the thoracic duct is usually required. Division of the

distal part of the internal, external, and anterior jugular veins facilitates visualization of the venous confluence at the origin of the innominate vein. The internal jugular vein can be li- gated to increase exposure of the subclavian vein (Fig. 38-7). If the subclavian vein is involved, it can easily be resected after proximal and distal control has been achieved. Direct extension of the tumor to the innominate vein does not preclude resection.

distal part of the internal, external, and anterior jugular veins facilitates visualization of the venous confluence at the origin of the innominate vein. The internal jugular vein can be li- gated to increase exposure of the subclavian vein (Fig. 38-7). If the subclavian vein is involved, it can easily be resected after proximal and distal control has been achieved. Direct extension of the tumor to the innominate vein does not preclude resection.

Figure 38-6. Anterior transcervical approach, as described by Dartevelle and colleagues.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|